Ernest Green was scared as any teenager would be seeing a mass of angry people hurling insults at him and threatening him with physical harm. Backed by the Arkansas National Guard, they infamously stood in the way of him going to school on Sept. 4, 1957. But Green knew that one way or another, he would have to get in those doors.

“It was very last minute that the National Guard were called – the day before school,” Green remembers. “It was a scary proposition for us but it seemed to me that if the governor was going through all of that trouble to keep me out that there had to something inside that high school that was very important.”

A member of the “Little Rock Nine” that famously first integrated Little Rock Central High in fall of 1957, Green will be the keynote speaker at the 31st Annual City of Madison & Dane County observance of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday on Monday night. He says he plans to speak about the impact of Little Rock Central High School in regards to the African American community going forward. “There will be some introspection and hopefully some ideas of what we can do moving forward to make further changes,” Green tells Madison365 in an interview from his home in Washington D.C.

In September 1957, nine courageous black students enrolled at formerly all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, testing the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Until the court’s decision, many states across the nation had mandatory segregation laws, requiring black and white children to attend separate schools.

“If you remember, our entrance to Central [High School] was three years after that Brown decision,” Green recalls. “Little Rock was really probably the largest southern city that attempted to comply with the court decision. They had been sued by the local NAACP. In the spring of 1957, I had the opportunity to indicate that I was interested in transferring from the all-black high school [Horace Mann] I was attending at the time to Central.”

But Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus famously called the National Guard on Sept. 4 to prevent the Little Rock Nine from attending high school that day.

Woodrow Wilson Mann, the mayor of Little Rock, asked President Dwight D. Eisenhower to send federal troops to enforce integration and protect the nine students. On Sept. 24, President Eisenhower sent in 1,200 members of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and placed them in charge of the 10,000 National Guardsmen on duty. Escorted by the troops, the Little Rock Nine attended their first full day of classes on September 25. “I went to school with the 101st Airborne,” Green remembers. “That is something I will never forget.

“There was a great deal of hostility by some students,” Green adds. “Probably the bulk of the students did what I hope doesn’t happen as much today – they sorta stood by. They watched the harassment, the breaking into our lockers, cursing us and spitting on us.”

The “9” were a pretty tight group. They had to be. “We were focused and very good students and we were able to work through that year,” Green says. “It was a club that was formed on the 4th of September. The membership was open for about five minutes and then it was closed after that.”

Green didn’t have to go to Central High but he wanted to do it for a number of reasons. “One, I lived in that central school zone and was quite familiar with it. Secondly, Central had a reputation for being one of the best high schools in the mid-South and I saw that as an important stepping stone in what I wanted to do in my life,” Green remembers. “Thirdly, as a black teenager growing up in Jim Crow segregated back-of-the-bus Little Rock …. that was an era that I wanted to try and help change.”

Green didn’t meant to start a revolution — he just wanted to go to school — but the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School was a defining moment in the American Civil Rights movement. “I didn’t know how I was going to change it but I knew that people like Jackie Robinson had advocated for change and were participating in it,” Green says. “When the moment came for me, I wanted to try and do my part to change the world order.

“It’s how we got to the Voting Rights Act and public accommodations,” he adds. It’s how we got to Barrack Obama as president of this country.”

Could Green ever imagine that one day there would be a black president of the United States of America?

“I clearly didn’t ever think in 1957 that it was possible to have an African American president of the country, but I didn’t know that I could ever attend Central High, either,” he says. “It was just a series of things that happened and I was fortunate that I got support from home and friends and family and church.”

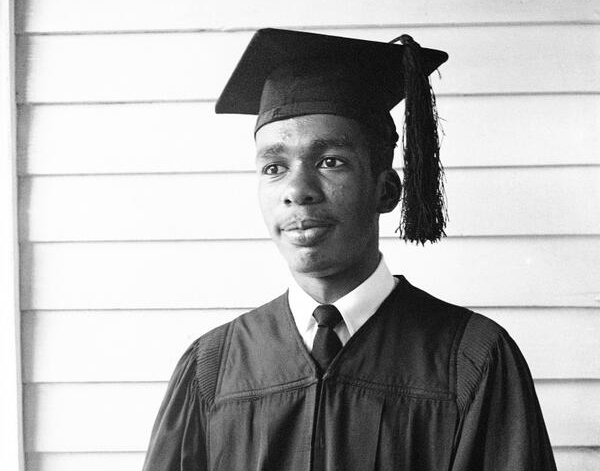

Green also got support from a very special guest at his graduation ceremony from Little Rock Central High School in 1958 – Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Dr. King was speaking at a college close to Little Rock that day. He indicated that he wanted to watch my graduation and he sat with my family,” Green remembers. “I didn’t know that he was there until after the ceremony. Dr. King gave me a graduation gift – a check for $15! I was deeply honored that he wanted to attend my graduation.”

Does Green ever think about what the Little Rock Central High atmosphere would been like in today’s day and age with intense social media and Facebook and Twitter and Instagram? “I imagine that would have made it an even bigger ordeal. But it was quite the ordeal as it was,” he says. “I’m glad that I had the chance to participate in something like this as a young person. My vision in 1957 was that it could improve things for myself, my family, and my community. It turns out, that that wasn’t such a far-fetched view of the world. I’m happy that I had a chance to play a small roll in that.”

Green, along with the other eight students, was presented by President Bill Clinton with the highest honor this nation gives to a civilian — the “Congressional Gold Medal” — for his outstanding bravery during the integration of Little Rock Central High School in 1957. In 2005, Green and the other Little Rock Nine were honored with a commemorative stamp by the United States Postal Service, and in 2007 President George Bush signed an executive order authorizing the U.S. Mint to issue a one-dollar coin commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the “Little Rock Nine.”

The “9” were also honored at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library last year. “Eight of us are still surviving and we are spread out all over the world,” Green says. ““We still are really good about keeping in touch with each other today.”

After graduating from Little Rock Central High, Green earned a bachelor’s degree in social science and a masters in sociology, both from Michigan State University. Green had a successful career in finance and was appointed to Chairman of the African Development Foundation by President Clinton. He was also appointed by Secretary of Education Richard W. Riley to serve as Chairman of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities Capital Financing Advisory Board. Earlier, Green served as Assistant Secretary of Labor for Employment and Training during the Carter Administration.

Several books, movies and documentaries have been produced chronicling Green and his eight classmates’ historic year at Central High School in Little Rock — including The Ernest Green Story, produced and distributed by the Walt Disney Corporation. Green has become a popular speaker and spokesperson and gets a chance to meet a lot of young people around the United States. Some know of him and the “9,” he says, … others don’t.

“We try to get young people to understand that this history was fairly recent,” Green says. “I think when they see a statue of Dr. King, it’s just another statue for some people, but his teachings are that much more important given the difficulty that we are encountering now with the community/police relations, issues of diversity and higher education. Many of these issues are the same as we had in 1957. I think that many young people understand that this is a marathon; not a sprint. We started making changes back in the day, but there is still much to do. They have a role to do that.”

Is the covert racism that African Americans face today much different than the overt racism Green faced in the Deep South?

“Racism is racism,” Green says. “But the face of America is changing and there are a lot more people of color today. America is not what it was in 1957 and I’m glad I played some small part in trying to change that.

“I think the movements of today like the Black Lives Matter movement are important, too,” he adds. “Probably, black lives matter were the first slaves that got off the ship in 1619 in Jamestown. All of this has been a continuum to try and improve lives for all Americans and, particularly those of us with ancestors that came from Africa. Basically, we’ve been 150 years out of slavery and we have to get people away from that mentality. We all all equal. The essence of this society is how we find a place for everybody.”

Green is looking forward to his big day in Madison, a city that he says that he is no stranger to.

“I’ve been to Madison a number of times,” Green says. “I think the Wisconsin Historical Society has papers from [president of the Arkansas NAACP] Daisy Bates from when we were at Central. She was the most prominent adult at that time. I was there for the unveiling of her papers.”

Green says that he hopes people remember the Little Rock Nine as being a part of a long movement to change the nature of this country; to open it up and to make it more equal for everybody. “We do things hoping that down the road it will open things up for people to be able to do more things – be the chancellor of the University of Wisconsin System some day, for example,” Green says. “Nothing should be beyond the ability to dream and think about it.”