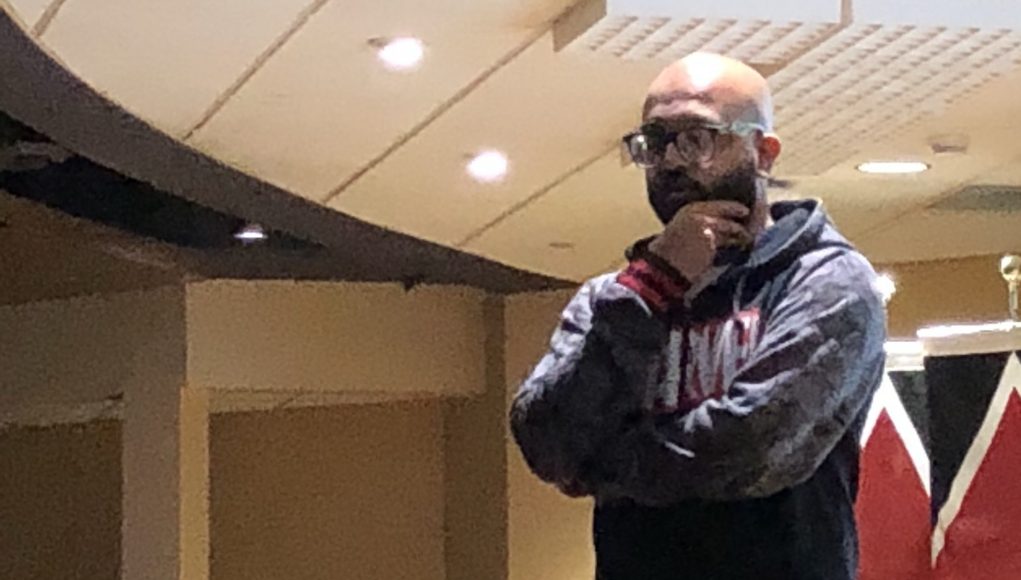

Journalist and comedian Aman Ali stopped by Edgewood college last week Wednesday to dispel some myths and answer some of Madisonians’ most burning questions about his Muslim faith.

As an Ohio native and second-generation Indian-American, Ali used his comedic background to share his own experiences growing up Muslim.

The event began with Ali giving a crash course in what he called “Islam 101.” He gave basic background on the faith and addressed some common misconceptions about Islamic links to terrorism and the unwillingness of many people who practice the faith to denounce acts of terrorism. Ali believed many of the misconceptions stem from skewed news reporting.

“We don’t see a lot of stories because it’s not considered sexy TV,” said Ali, who used to write and report for The Hill and Reuters. “I used to work as a reporter and it’s frustrating to see certain types of stories just not covered,” he said, noting that this happens to all underrepresented groups, no matter their religious or political affiliations.

The majority of the event served as a Q&A where Ali welcomed the audience to ask him literally anything.

“I’m Muslim, ask me anything,” he said. “You want to talk about Islam we can talk about that, you want to talk about sports we can talk about that, if you want to ask me about girl problems, I probably can’t help you with that because I have my own,” he joked.

Audience questions ranged from being about Islamic faith and women’s access to education to Ali’s travels chronicling the lives of Muslims in America.

“Did you have any negative experiences when you were doing your 30 day travel,” asked one audience member of Ali’s short documentary films during which he travels to different Mosques throughout the country.

He responded with a story about going to a small town in Georgia covered in confederate flags, where he encountered kindness and acceptance, instead of the discrimination he anticipated.

“I found myself reflecting on this idea that everyone hated me because of my identity, especially when I was traveling through the south,” Ali said. “I thought I was going to be changing people’s minds, but it turned out to be the other way around.”

Ali noted, though, that their kindness did not erase or normalize the confederate flag and its racist ties to a history of slavery.

He also shared a story of being in high school and confronting a classmate who called for Afghanistan to be bombed as a result of 9/11.

“I remember asking, why kill all these people who had nothing to do with it, how is that justice,” Ali said, to which the classmate responded that Ali’s father must’ve been flying the plane.

“I got so mad and I got this close to punching in him, but when I looked in his face he was just smiling and nodding his head,” Ali said. “And that face haunted me because he’s probably going to go his whole life thinking Muslims are bad and he’d be able to say he met one who punched him in the face.”

The incident made him conscious of how he represented himself. Three years ago though, Ali said the same person messaged him an apology on Facebook, because he too had been haunted by his words to Ali.

Ultimately many of Ali’s stories and answers emphasized open-mindedness and the realization that people are more alike than they are different.

“I think we’re all hungry to learn about other people and other cultures and that’s why I wanted to take this opportunity to have these conversations,” he said.