While Wisconsin may have been the first state to grant black men the right to vote in 1866, that right did not come without a fight and without consequences for black Americans living in Wisconsin.

Christy Clark-Pujara, Ph.D., associate professor of history for the Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, illuminated the history of black male suffrage in Wisconsin at the State Historical Society on Feb. 20.

She explained that the story of black suffrage in Wisconsin is ‘recent history’ and plays out amidst European invasion, colonization and the removal of indigenous people.

Black people first came to the Midwest in the 1720s as part of the French Fur Trade. Some were free, but most lived in bondage and by 1732, enslaved people made up a quarter of the population.

She said that the history books don’t talk about slavery in the Midwest, but at the time 41 percent of white head of households held people in bondage. While the numbers were small, the slavery was more widespread than in the south where just 24 percent of populations held slaves, but in larger numbers.

Even though the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 forbade slaveholding in the territories, the ban was not enforced and “race-based slavery was practiced in the Midwest until the late 1840s.”

“When significant numbers of white Americans from the Northeast and upper south began to move to the Midwest after the American Revolution, the number of enslaved native Americans dwindled as the United States army forcefully removed them from the land and some American Indian tribes entered into treaties with the US government.”

African Americans who were enslaved – and some free – remained. More enslaved black people came with white settlers who also brought racist attitudes. Enslaved people were present in every facet of the economy.

“They labored on farms, in the skilled trades, as domestics and miners,” she said.

In 1827, Henry Dodge, who became the first territorial governor in 1838, moved to the lead region of southwestern Wisconsin from the slaveholding state of Missouri. He brought his slaves Toby, Tom Lear, Jim and Joe to work his lead smelter.

“He held Toby, Tom Lear, Jim and Joe in bondage and promised to free them after six months,” Clark-Pujara said. “He held them for 12 years despite the prohibition of slaveholding in the Northwest Territories.

“In the Midwest, slavery was openly practiced, but it was rarely acknowledged,” she continued. “It was a fluid institution taking on a variety of forms including open and legally sanctioned slavery, long-term indentured servitude, adoptions that were intended to mask child slavery and outright illegal slaveholding.”

The fight for freedom was well documented in Wisconsin.

In 1846, Paul Jones, an enslaved lead worker in Sinsinawa, sued his enslaver George W. Jones for $1,133 for trespassing on a promise, a promise to pay him wages. Paul Jones lost his case because slaves were not considered citizens, and therefore could not claim lost wages. He continued to labor for George Jones’ benefit until 1842 when he was emancipated. Jones would ultimately settle with other emancipated and fugitive blacks in the farming community of Pleasant Ridge outside of Lancaster.

Clark-Pujara explained that even though by 1840 only 11 of 196 black people in Wisconsin Territory were enslaved, “the existence and the practice of race-based slavery in Wisconsin shaped white attitudes about African Americans because they, like the rest of white Americans, associated slavery with blackness, the antithesis of citizenship.”

“Race determined who belonged in this place, who had a right to this place, and who should homestead in this place,” she said.

Fear of black migrants led white Wisconsinites to dispute abolition and the rights of black residents. So while the state served as safe haven for fugitives like Joshua Glover, black men were barred from voting until 1866, a few years before the 14th and 15th Amendment that declared birthright citizenship and universal male suffrage.

“So many times the history of black people in Wisconsin has been a history that focused on abolition and the underground railroad rescue of Joshua Glover. All of those things happened and all of those things matter and tell us a lot about the past and the people who live here, but at the same time Wisconsin was a place that denied black men suffrage.”

The debate about black male suffrage began with Wisconsin’s first constitution in 1846 (that never was passed), and set the tone for future discussions. Opponents deemed it an “infringement upon their (white) natural rights” while advocates called the denial of the vote an “affront to all people.” The second constitution of 1848, when Wisconsin became a state, “explicitly excluded black men from the electorate” stating that “adult white men, even non-citizens could vote as well as native men who were citizens and denounced all tribal affiliation.”

“To be white meant to be a citizen. So you could be two months in the nation from Germany or Norway or Sweden and your whiteness immediately bought you privilege and power, because you didn’t need citizenship, you just needed whiteness,” Clark-Pujara said.

The first referendum on black suffrage occurred in 1849 and passed on a vote of 5,265 to 4,075. However, 31,759 people abstained from voting and as a result, the State Board of Canvassers incorrectly declared the abstentions as no votes and the referendum failed.

In 1855, the Wisconsin Republican party adopted black male suffrage as part of their party platform but abandoned it two years later. Meanwhile, the Democrats adopted a resolution stating that they were “unalterably opposed to the extension of the right of suffrage to the negro and will never consent that the odious doctrine of negro equality shall find a place upon the statute books of Wisconsin.”

A referendum in 1857 validated the white position and suffrage failed again on a vote of 45,157 to 31,964. Black Wisconsinites petitioned the state to afford the right to vote and some even presented themselves on election day.

A final referendum on suffrage occurred in 1865 and once again was voted down.

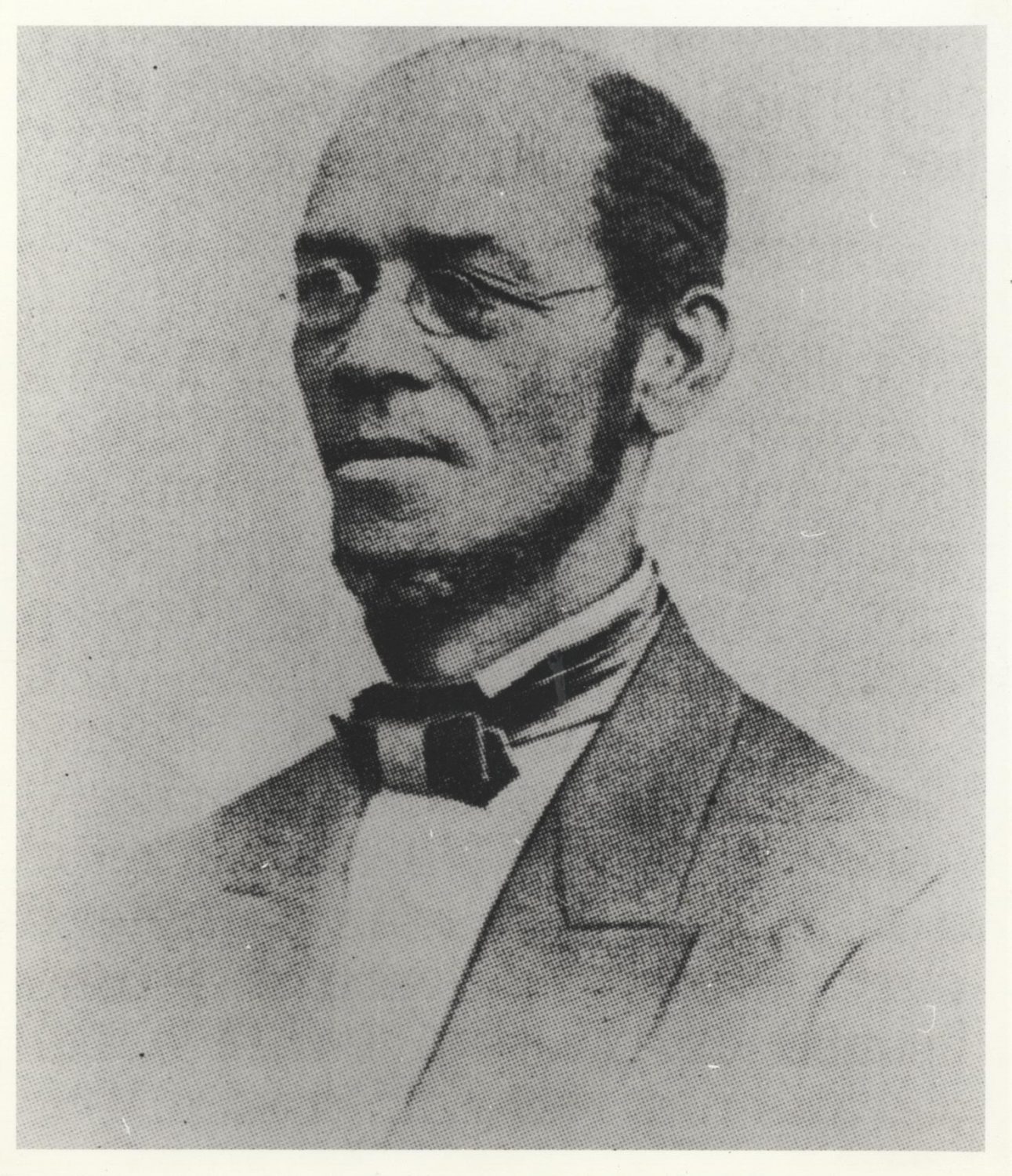

“That would have been the end of it except for a man name Ezekiel Gillespie,” she said.

Gillespie attempted to vote and was turned away and later sued the state. The case made it to the Supreme Court of Wisconsin. “The court agreed that Gillespie had indeed had the right to vote as the 1849 referendum had been wrongly interpreted by the state board of canvassers,” Clark-Pujara added.

After 17 years, black men achieved the vote in 1866.

During those 17 years, “black men in Wisconsin were barred from the ballot box and their disenfranchisement excluded them from shaping the state’s public institutions including the campus I work on,” she said.

Women would be granted the right to vote on June 19, 1910.

In closing, Clark-Pujara reminded us that while blacks were a tiny minority in Wisconsin, it’s important to tell their stories.

“Enslaved and free African Americans lived, labored and raised families on the Wisconsin frontier,” Clark-Pujara said. “They called Prairie du Chien, Racine, Green Bay, Lancaster, Milwaukee, Madison and Menomonee home. Yet their stories remain largely untold. The history of the state and region remains incomplete without a full accounting of the African American experience and influence.”