Recently, I have been asked on more than one occasion, why much of my work over the last couple of years has contained the word “Of” in the titles.

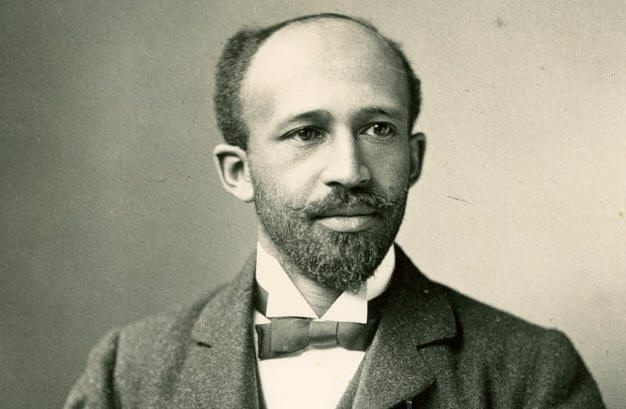

It occurs to me to explain why this is so. In his 1903 text, The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. DuBois offers commentary and insight on the condition of black Americans in the early 20th century.

In his text, Dr. DuBois titles every one of his commentaries and larger observations with titles like “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington” and “Of the Meaning of Progress.”

Dr. Dubois did so not to be pedantic, but rather to accurately describe the pattern of his analysis of the black community. At the time, his was an in-depth study “of” the Black community, rather than one “about” it. The difference isn’t all that subtle.

Dr. DuBois’ work lays the foundation for, and is the measuring rod of, all commentary and scholarship regarding black America. His work has made the work of Carter, Kelsey, Locke, and even Angela Davis and Bell Hooks, make sense to us.

I am respectful of Dr. DuBois’ work. To that end, the “Ofs,” for me, are an acknowledgement of that respect. It is an admission, that any time I attempt to pen or type or say something coherent about the liberation of black people, Dr. DuBois has already said it. Better.

For instance, every day I attempt to explain the economic, political, and social struggles of black people in a manner that makes sense, and is also accurate.

In the black reality I see, there are several dilemmas. Black Americans long to connect to their African and Afro-Caribbean origins, but they exist in a context in which their history begins with slavery.

In this reality, I also see black Americans who must not only see the world through their own eyes, but also through the eyes of their white counterparts.

This, in essence, means black Americans must have a considerable understanding of both black and white culture.

It also means that black Americans second guess their own culture and vehemently eschew stereotypes of black life.

Many black Americans dress up any time they are out in the streets, and avoid dancing, eating watermelon or fried chicken, lest they be labeled lazy and shiftless.

It also gives way to a hatred of self. When black Americans see themselves as others see them, they learn to loathe their skin color, the physical features that make them beautiful, and find a motive to be suspicious of anyone else who looks like them.

Dr. DuBois summarized what I have attempted to say in a career, ideally in one paragraph of The Souls of Black Folk:

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

In fact, Dr. DuBois captures and summarizes black life so well and so timelessly in this passage, we have given its philosophy a name — double consciousness.

A double consciousness that exists even today. A double consciousness my writings are a product, of.