From Tone Madison

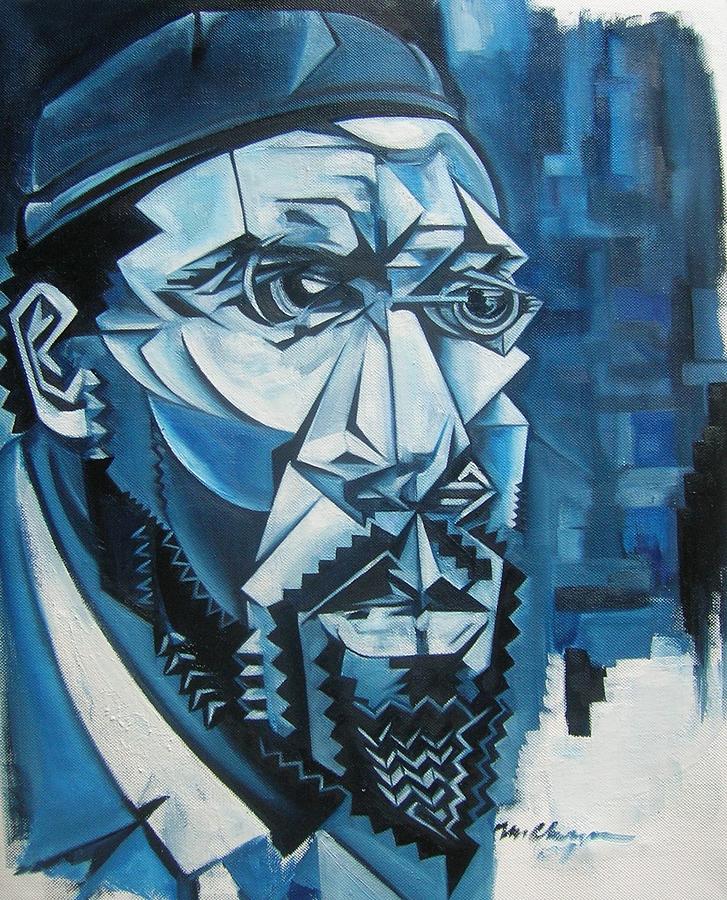

The brilliant jazz pianist and composer Thelonious Monk will be channeled through both music and visual art on Saturday, August 15, 8:30 p.m., at Madison’s Harlem Renaissance Museum on East Wash. Wisconsin jazz outfit Lesser Lakes Trio—Madison-based bass player John Christensen, Milwaukee drummer Devin Drobka, and Racine-based trumpeter Jamie Breiwick—will play a set of Monk’s compositions, and Madison-area painter Martel Chapman, who draws on Cubism to create dizzying portraits of jazz musicians, will be displaying some of his Monk-inspired work.

The Lesser Lakes Trio usually focuses on original compositions and freewheeling improvisation, but Drobka and Breiwick also play together in a Monk tribute project called Dreamland. Lesser Lakes are currently preparing material for a new recording to follow their free debut album, and Drobka is composing new material for another project he leads, Bell Dance Songs. Ahead of Saturday’s show, Drobka talked with me about playing Monk tunes without a piano and the enduring mystery and challenge of Monk’s compositions.

Tone Madison: The obvious, maybe dumb thing to point out is that you’re playing Thelonious Monk songs here, but there’s no piano in Lesser Lakes Trio. How are you approaching these compositions in a piano-less way?

Devin Drobka: I think the nice thing is that because Monk was such a melodic player, his melodies, at least for me, are kind of the guiding light that he would tell a lot of people to play off of. They’re so centered around that, and he improvises around the melody a lot. We don’t have to be bound by any of those harmonic restrictions that maybe a pianist or guitar player would have. We have a little bit more range where John then can take on some more of that responsibility, or even I can take on some of that responsibility. For us, it just opens up the music even more, if we were hearing certain ideas or wanted to expand a little bit. It’s a little more freeing, which is nice. We can breathe a little bit on the tunes and hear everybody. It allows us to hear the tunes in a different way, because we don’t have the piano there.

TM: And when people think of his music, they tend to think of his really distinctive approach to the piano, but the compositions themselves are complex, too.

DD: It’s nice to get away from thinking that you have to do things exactly how they did. Monk rarely played with trumpet players, so having the music be far away enough that we can respect and honor it using more of the other aspects that we find, or that Monk himself even talked about in his music, is nice.

TM: It’s funny that you mention Monk not often playing with trumpet players, because there’s a part in Miles Davis’ autobiography where he recalls trying to play with Monk and how difficult and frustrating it could be. He talks about how challenging it was to get things down to Monk’s satisfaction.

DD: You realize how hard the music is, even just trying to play it in a quartet. He thought about everything. All the pieces fit, the rhythm, the melody and the harmony. It makes you realize sometimes where other music falls short. If you take a part out, it feels a little empty. I think that’s why doing it in a trio is exciting, because you can think of the trumpet as the melodic voice and the bass as harmony, and then I’m taking care of rhythm. At least for us, how we all play, at times that pole can shift, so maybe Jamie will take harmony and John will take the rhythm and I might take the melody. We can do that.

TM: It definitely goes back to the myth that surrounded Monk, where people perceived him as just this nut, but in fact he knew what he was doing on a really sophisticated level.

DD: And I think that’s part of the game. Man, if you can get everybody to think you’re crazy [laughs], then I think you’ve also done something beautiful. You’ve held a mirror to everybody. And maybe Monk was a little bit crazy, but everybody’s a little crazy, then. In that era, too, there’s so many social and cultural factors. He wasn’t crazy. He was just a very intelligent person. Whenever anybody’s functioning on that plane, I think the music does something to you in a different way. Like I said, why does everybody still copy him? I’m so intrigued by that, about these individuals who have such clarity. It’s amazing. But I think maybe he exposed that everybody else is crazy! [Laughs]

TM: Are there any tunes in particular that you’re looking forward to playing at this show?

DD: I think we always do “Ask Me Now,” which I love. I love the strolling ballads that Monk does, like “Ruby, My Dear,” “Ask Me Now.” What else are we gonna do? “We See,” I love that one, that’s a funky number. We’ve talked about wanting to do some of the ones that aren’t played as much, like “Oska T.,” which is only like a 16-bar tune but there’s so much in there and it’s awesome. Then “Ugly Beauty,” this tune in 3/4—I guess it’s the only song that Monk wrote in 3/4. I gotta see what other ones we’re gonna do. It’s funny, people often end up playing the same Monk songs, like “Rhythm-A-Ning” or “In Walked Bud,” which we’ll probably do, because for a while I hated those tunes, just because of how everybody else was playing them. But I think when you get the right people, then it’s fun again. There’s some weird ones like “Stuffy Turkey,” there’s so many. But I think we’re gonna try some different ones, because there are a lot that are still unplayed by a lot of people. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s because the music is that hard. [Laughs] There’s a few compositions that are always done and some that aren’t, and we’re getting to the point where we want to explore the ones that usually aren’t. I don’t want people to be beaten over the head with, “This is what Monk did and this is it.” This guy’s music is still a lot of the unknown.

Thelonious Monk will be channeled through both music and visual art on Saturday, Aug. 15, at the Harlem Renaissance Museum, 1444 E. Washington Ave.