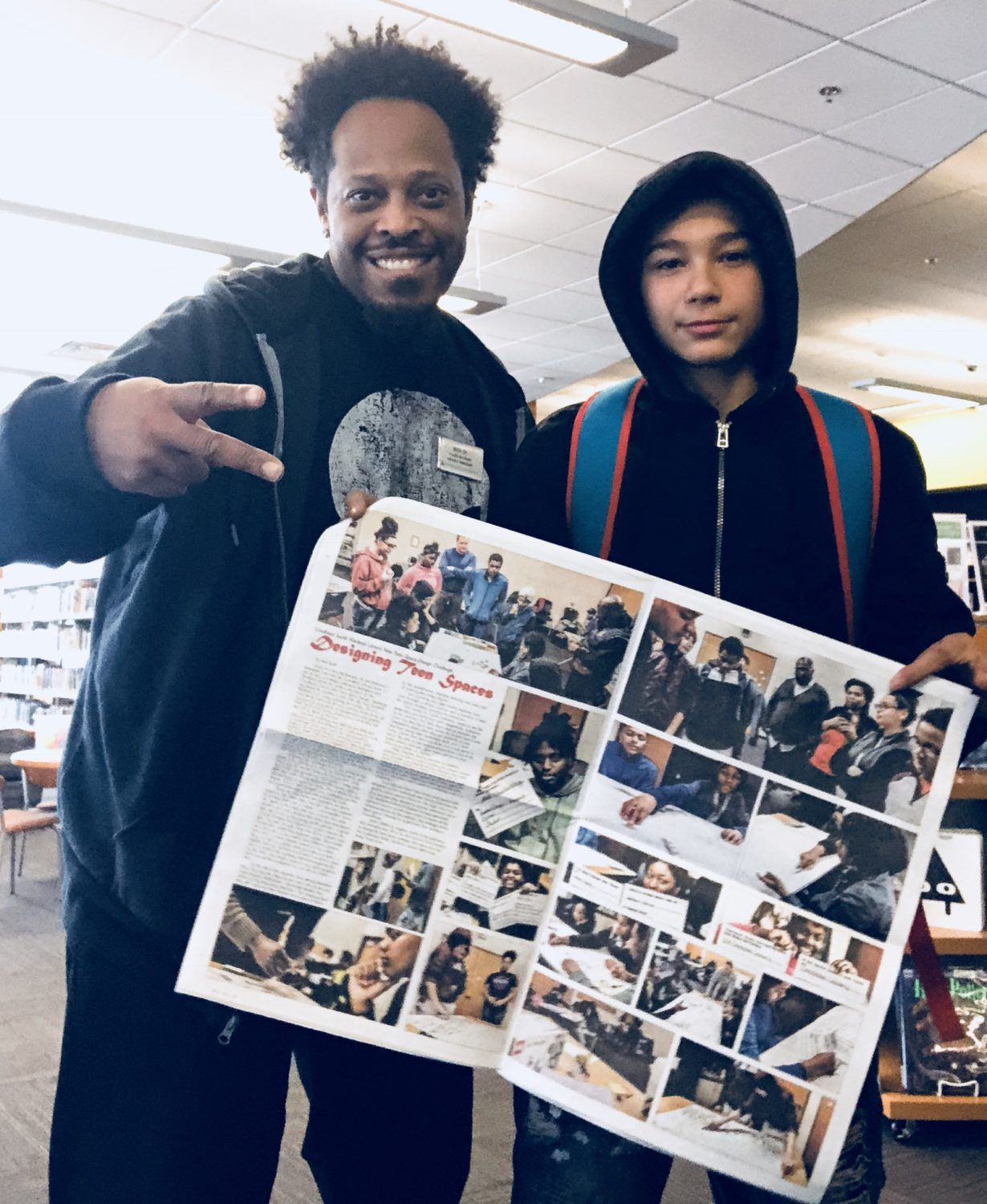

“I’ve seen the inside of prison so I’m living a dream,” said Will R. Glenn Sr., the first Black Teen Services Librarian at Goodman South Madison Library. “But a little dude from 16th and Locust never thought in his wildest dreams he would be a librarian in Madison, Wisconsin … never thought that in life.”

Glenn was born and raised in Milwaukee and earned an undergraduate degree in sociology with a minor in human resource management and a master’s degree in organizational management and leadership from Springfield College at a satellite site in Milwaukee. Glenn is also a member of the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity.

Glenn got his start in the public library system after a meeting with the father of one of his fraternity brothers who encouraged him to join the board of directors at a local library.

At the time, Glenn was working as the assistant director of Meadowood Neighborhood Center in Madison adjacent to the Meadowridge Library.

“Midway through that board year, someone came to me from the library, ‘I’ve heard about all the good things you’ve done in the community. You should think about working for the library’…..[b]ut at that time I just like, ‘man, I’m from the hood, I’m from the inner city of Milwaukee, working at the library is probably the corniest thing that you can say to me.’

“But the more I worked with the library, on the center side, I was like, ‘maybe the library could allow me to do some things that I wanted to do that I could really do,’ Glenn said. “Because there were no people of color really working for the library that I knew, especially people of color who had any kind of power.”

Upon receiving a position as a library assistant, Glenn began to realize the lack of racial diversity within the library system, specifically regarding his position. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, African Americans comprise roughly 14,250 of the estimated 190,000 librarians in the United States,

“So there wasn’t like another brother that could take me out on his wing and show me how this goes and how library people are,” he said.

As such, Glenn has always tried to be “a conduit” for BIPOC youth in community spaces.

“Most of the people that are not like us that work for the library, we care, but we don’t know how to touch the people that we want to,” Glenn explained. “They like, ‘yeah, we got this library in the hood’ and I’m like, ‘Nah, stop talking’ because to the hood it looks like it’s a whole bunch of white people sitting around talking about how they gonna serve Black people, but you ain’t got no Black people to be the conduit.

“In the African American community, your library is viewed a certain type of way. And I always have this saying, like, in our community, that the library is not church and it’s not school, but you’re not at home,” Glenn continued. “So, it’s a weird space for kids to come and kind of figure out how they want to act or how they want to be, especially when they don’t see anybody that looks like them.”

As a library assistant, Glenn noted that libraries have turned into “community centers” for BIPOC youth.

“You can clearly see that the three libraries that were in underprivileged neighborhoods are really staffed with people that can’t relate to the people that are regular patrons at the library,” Glenn said.

“So we get into a more or less of a thing where the people in the library are trying to, for lack of a better word, control our kids or get them to be a certain type of way instead of engaging your community and the kids in the community,” Glenn added.

Once the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Glenn became unemployed until he was re-offered his current position as now Teen Librarian for the Goodman South Madison Library.

Glenn emphasized the importance of having Black practitioners in library spaces — but as leaders, not as tokens.

“We need people of color in libraries to help serve those patrons that come in there,” he said.

Glenn also noted that not only is it essential to have youth practitioners of color, but libraries must encourage equity, especially in how youth are color are being treated in said spaces.

“So coming out of COVID, we are trying to at least have something to show that kids are a part of the fabric of these buildings and y’all not just finna have them and start calling the police on them,” Glenn said. “That’s not what’s going on here. We need to engage. As soon as they come in, just look them in the eyes, you don’t even gotta say nothing, just look them in the eye. Next time, you might wink or you might give them a head nod or something. But you have to do something, because those things will help you when you gotta ask them to not do something. The first point of contact cannot be like ‘shh’.”

Prior to his current position, Glenn worked in a variety of community and youth spaces including as the East Side Support Services Coordinator for the UW-Madison PEOPLE program and the Out-of-School Youth Coordinator for the Madison Metropolitan School District. Glenn also engaged in contract work for the Goodman Library.

“The PEOPLE program at UW kind of gave me my seed as far as being in the community and with the kids,” he said.

Glenn urged youths to understand that you can make mistakes but “can still come out on top and live your life.”

“I suffer from PTSD. So I just engage with the whole African American male mental health thing. And my whole thing is to show people like, ‘Dude, I’m just like you,’” Glenn said.

Currently, Glenn is working on creating a program for underprivileged youths in the Madison community.

“Because most kids or adults are one foot in, and one foot out, in the bad,” Glenn explained. “So that’s my goal is to develop that but be able to provide opportunities to those who have one foot in and one foot out.

“So my whole thing with this whole thing is to be more like: if you can see it, you could be it and you can achieve it.”