It is mid-March, and two researchers trudge on snowshoes through feet of snow on a wooded trail, dragging a small plastic sled full of equipment.

Scientist Carl Watras’ snowshoes are rigged with rubber from bicycle tires to bind the webbed contraptions to his feet. His research assistant, Jeff Rubsam, runs ahead to guide the sled down a steep, snowy slope towards a frozen lake. Watras descends, planting one long leg slowly after another.

Watras has been making this trek for 32 years. He studies how the neurotoxin mercury accumulates in lakes and in Wisconsin’s fish.

Watras and Rubsam walk onto frozen Little Rock Lake in Vilas County near their base at the University of Wisconsin’s Trout Lake Station. They are scientists for UW-Madison’s Center for Limnology and the state Department of Natural Resources.

(Sarah Whites-Koditschek / Wisconsin Public Radio)

Rubsam walks briskly ahead with the sled towards the center of the lake. He pulls out a shovel and clears a large circle. He then pulls out a power auger and begins drilling into the ice to collect water samples.

“The ice is frozen on top and then there’s kind of a slush layer in there and then you start into hard ice again,” Rubsam said.

After decades of water sampling on Little Rock Lake and two other nearby lakes, Watras has concluded that climate change is causing fluctuations in the level of dangerous methylmercury in the environment. The finding adds to the list of negative effects of climate change, which include making storms more powerful, increasing the Earth’s temperature and causing polar ice to melt, which causes sea levels to rise.

Watras has discovered that accumulations of the toxin in fish fluctuate as water cycles driven by climate change raise and lower lake levels. When the water levels go up, Watras found, levels of mercury can increase to unsafe levels in walleye, one of the state’s most prized game fish. When levels go down, concentrations in walleye go down to levels considered safe by the Environmental Protection Agency, or 0.3 micrograms per gram.

He called the findings “a complete surprise.”

“We had no idea that water levels in lakes … could affect the production of methylmercury,” he said.

This dynamic was previously seen in reservoirs, where levels tend to fluctuate. But Watras said this phenomenon, and its implication for fish, was not understood for lakes until his study. He added that there is little similar data that spans three decades, allowing a glimpse at longer-term climate-related trends.

The state DNR already recommends limiting intake of fish from most of the state’s 15,000 lakes because of mercury.

Nationwide, mercury concentrations in fish are above the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s human health limits in one out of every four streams, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. And about half of all lakes and reservoirs have fish with mercury above EPA’s recommended limits.

((Sarah Whites-Koditschek / Wisconsin Public Radio)

Mercury can cause brain and kidney damage, especially in children, and it can be transmitted between mothers and babies, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the amount of mercury in the global atmosphere has doubled through human behavior since the pre-industrial era. Humans have added mercury to the environment in products such as medical thermometers, paint, batteries, certain manufacturing processes and by coal- and oil-burning power plants.

Efforts to reduce mercury in the environment are hotly debated, as cutting emissions from power plants, the main source, can cost billions of dollars. The Trump administration is seeking to roll back Obama-era federal mercury regulations, saying the cost is not worth the health benefit. Meanwhile, activists are concerned about mercury discharged by We Energies’ Oak Creek power plants into Lake Michigan.

Gains made in controlling mercury through regulation may be obfuscated as the planet’s climate continues to change, causing dips and spikes in the mercury levels of fish, making it harder to protect people — and the planet.

The mercury ‘roller coaster’

Noelle Selin, associate professor in atmospheric chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said mercury regulations on power plants have largely worked. But going forward, understanding how climate change impacts mercury in the environment will be key to gauging what level of regulations are needed to see improvement, she said.

“If we don’t account for (climate change), we might, for example, miscalculate the amount of emissions reduction needed to achieve fish methylmercury declines, or misjudge whether mercury emission controls have been effective or not,” Selin said.

Climate change is already mobilizing mercury in the environment, according to Selin. Wildfires, which have increased with climate change, release mercury into the atmosphere. And hotter weather, also tied to climate change, causes mercury to volatilize and be released.

Selin said historical mercury emissions make up two-thirds of the accumulation in the environment, and new emissions account for one-third.

“So this is why climate ends up being really important, because of this important impact of legacy mercury that continues to affect us,” she said. “The mercury that we’re emitting today turns into tomorrow’s legacy mercury.”

(Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

According Watras, humans’ exposure to the toxin will increasingly be like a “roller coaster.”

That may mean there is no longer a direct correlation between human efforts to reduce mercury in the environment and the amount of mercury that enters our food chain through fish.

Rules, tracking affected

Mark Brigham, a hydrologist at the U.S. Geological Survey in Mounds View, Minnesota, said fluctuating mercury levels could make it harder to know whether fish are safe to eat. People who fish could easily underestimate or overestimate the risk at any given time.

“It’s entirely possible that people, when they look at the fish consumption advisories for a given lake, they could be looking at advice that’s out of date or doesn’t reflect current conditions in the lake,” Brigham said.

After finishing the sampling, Watras walks over to a group of trees on the edge of the lake. These were once on dry land but now have been submerged in water. He said they will not live much longer.

“White pines have moved in and probably some white spruce, and they’re not used to having their feet wet,” he said.

In years when water levels are low, the forest “marches in,” Watras explained. When water levels rise and plants die, the decomposition process converts mercury already in the plant from rainfall into methylmercury, a form that is toxic to humans, he said. The toxin accumulates over time in the body of fish, posing a health risk to humans.

Mercury proposal stirs protest

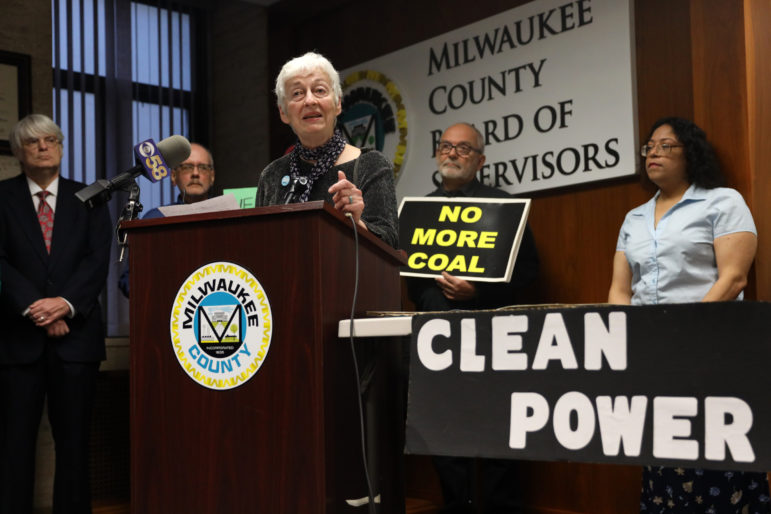

In late April, a group of protesters lined up to speak at a Sierra Club news conference in Milwaukee against a proposal to change mercury limits for We Energies’ coal-burning Oak Creek Plant.

The utility is seeking a variance from DNR’s recently applied mercury limits. Rather than being held to a 1.3 nanograms per liter monthly average, the utility would be allowed to release up to 4.1 ng/L of mercury on any given day. While company and state officials say the change in how mercury is measured should not increase the overall amount discharged into Lake Michigan, there is no guarantee — and that has activists concerned.

The limits proposed by DNR are meant to prevent a future increase of mercury discharge and are based on what the plant typically discharges, said Jason Knutson, DNR wastewater section chief. The proposal also includes a plan to reduce mercury discharge at the plant.

But the proposal has raised fears among environmental advocates that mercury output from the plant will increase.

“We Energies should be here today and they should be standing here apologizing for the polluting of Lake Michigan, not asking to increase that pollution,” said Julie Enslow of 350.org Milwaukee, a chapter of a grassroots climate-change movement. “They should be here today announcing the closure of the Oak Creek Power Plant and all its fossil fuel facilities and announcing to immediately begin moving to clean, renewable, sustainable energy with solar and wind.”

The news conference was held right before the Milwaukee County Board voted unanimously in favor of a resolution asking DNR to deny the company’s variance request.

We Energies spokesman Brendan Conway said the company is committed to decreasing its mercury emissions. Conway said there could be “peaks and valleys” in the amount, but that “overall, by the end, that (monthly) average is going to be 1.3.”

“Even with this variance, we have committed in the permit to continue to work to lower the level of mercury from the plant,” Conway said an email.

Knutson noted that other utilities on Lake Michigan have variances with higher concentrations of mercury discharge.

Regulations and other changes over the decades have reduced mercury in Wisconsin’s environment.

(Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

They include eliminating the use of mercury in commercial products, closing a smelter near the state’s northern border and cutting mercury emissions from area utilities, according to Watras’ study, which was co-authored by three other DNR officials — David Grande, an air toxics chemist; Alexander Latzka, a fisheries biologist; and Lori Tate, a fisheries database coordinator.

Adding climate change to the mix will make it harder to sustain those gains.

“We like to see progress in mitigating pollution,” Watras said. “So, in a way, it’s adding an additional complicating factor to our attempts to have a cleaner planet and a cleaner world.”

Sarah Whites-Koditschek is a Wisconsin Public Radio Mike Simonson Memorial Investigative Fellow embedded in the newsroom of Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org), which collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication.