As a child protective services worker questioned them in their baby’s hospital room, Greg and Katie Shebesta of Janesville, Wisconsin, held their nearly 6-month-old upright, allowing the excess fluid to drip through tubes a brain surgeon had inserted beneath his skull.

“He was trying to understand if I was a person who would hurt my child,” Katie Shebesta said.

Greg Shebesta remembered a torrent of fear washing over him that winter day seven years ago.

“I was afraid my kid was gonna die. I was afraid I was gonna go to jail. I was afraid they were gonna take them away from us,” he said, referring to Henry and his older brother Jack, who was 3 years old.

Dr. Barbara Knox, then-head of the University of Wisconsin’s Child Protection Program, had flagged the Shebestas’ case, alleging the baby’s brain bleeding was intentionally inflicted. That triggered an investigation that began even before Henry’s surgery.

Greg Shebesta researched possible medical reasons for his son’s condition on the internet. He shared his findings with Knox. She rebuffed them.

“Dr. Knox kept saying, ‘No, there’s no medical reason, this was intentional trauma, nonaccidental trauma,’ ” he recalled.

But Knox was wrong. And not just in that case.

In seven cases spanning seven years, the child abuse pediatrician labeled accidents and medical conditions as abuse — allegations later rejected by police, child protection officials and other doctors, Wisconsin Watch has found. They are among the families and caregivers who spoke to Wisconsin Watch after a 2020 investigation revealed Knox had wrongly suspected a Mount Horeb family of child abuse.

Blood clotting disorder blamed

Months after Henry recovered from brain surgery, a UW pediatric hematologist and oncologist told them Henry had a blood clotting disorder.

The brain bleeds that Henry suffered “very likely are entirely due to this bleeding tendency,” Dr. Carol Diamond wrote in a letter she sent in February 2015 to Knox and Rock County child protective services. She added: “I feel very confident in the care of this family for this boy.”

With the allegations behind them, the parents of now three healthy children detailed what Katie Shebesta called “some of the scariest and most traumatic” moments of their lives. The family would like to see accountability by the hospital — and by Knox — for the unnecessary trauma they endured.

“She was trying to prove (abuse) all at the expense of potentially our freedom, but more importantly, our kid’s life,” Greg Shebesta said.

Knox left the University of Wisconsin in 2019, after being suspended for allegedly bullying her hospital colleagues and now faces similar scrutiny at her new job at Providence Alaska Medical Center, where she heads the statewide child abuse forensic clinic, Alaska CARES.

Over the past two years, the Anchorage clinic has lost its entire medical staff to resignations or eliminated positions, according to a joint investigation by Wisconsin Watch and the Anchorage Daily News. Seven current and former Providence employees say they made dozens of complaints about Knox’s management and medical judgment to supervisors, with no response for months. Knox reportedly has been placed on leave. Providence declined to verify Knox’s employment status but confirmed it is investigating the clinic’s workplace environment.

Months ahead of publication, Wisconsin Watch sent Knox two emails containing investigative findings, questions and interview requests. She did not respond to emails or follow-up phone calls from Wisconsin Watch.

During Knox’s UW tenure, criminal and child welfare investigations upended the lives of many innocent families. Some cases mandated 24-hour in-home supervision for weeks as CPS and police investigations failed to find evidence to sustain Knox’s suspicions of child abuse.

Dane County Director of Human Services Shawn Tessmann said the CPS system is designed to have multiple checks and balances. She said abuse is substantiated in just 15% of cases referred.

“We are concerned that families are not unduly brought into the CPS system while also making sure that necessary protections are in place for kids who are at risk,” Tessmann said.

Directors of Human Services in Dane, Green and Rock counties, the three counties where all of the families lived at the time of their CPS referral, all said they use an initial assessment based on state standards to determine if the safety and wellbeing of a child are at risk.

Mandated reporters like Knox who claim they see signs of abuse trigger the CPS assessments. None would comment on their interactions with Knox.

“Only after this assessment is it determined if the allegation is substantiated or not based on the facts gathered,” Tessmann said.

UW Health told Wisconsin Watch it doesn’t track the number of referrals its child protection program makes to child welfare authorities and law enforcement each year.

However, all of the parents and caregivers who spoke to Wisconsin Watch were seen by Knox, Physician Assistant Amanda Palm, another member of the child protection team, or both. Some families asked for their names to be withheld because of the stigma of child abuse, fear of losing their jobs or the lingering trauma from the allegations.

The hospital declined interview requests on behalf of staff and administrators.

Families faced wrongful charges

Knox’s pursuit of allegations against them caused emotional trauma, unnecessary legal and medical bills and at least one initially missed diagnosis, parents told Wisconsin Watch. In the case of Henry’s clotting disorder, the focus on a child abuse diagnosis over the actual cause of his brain bleeding could have threatened his life, the Shebestas say.

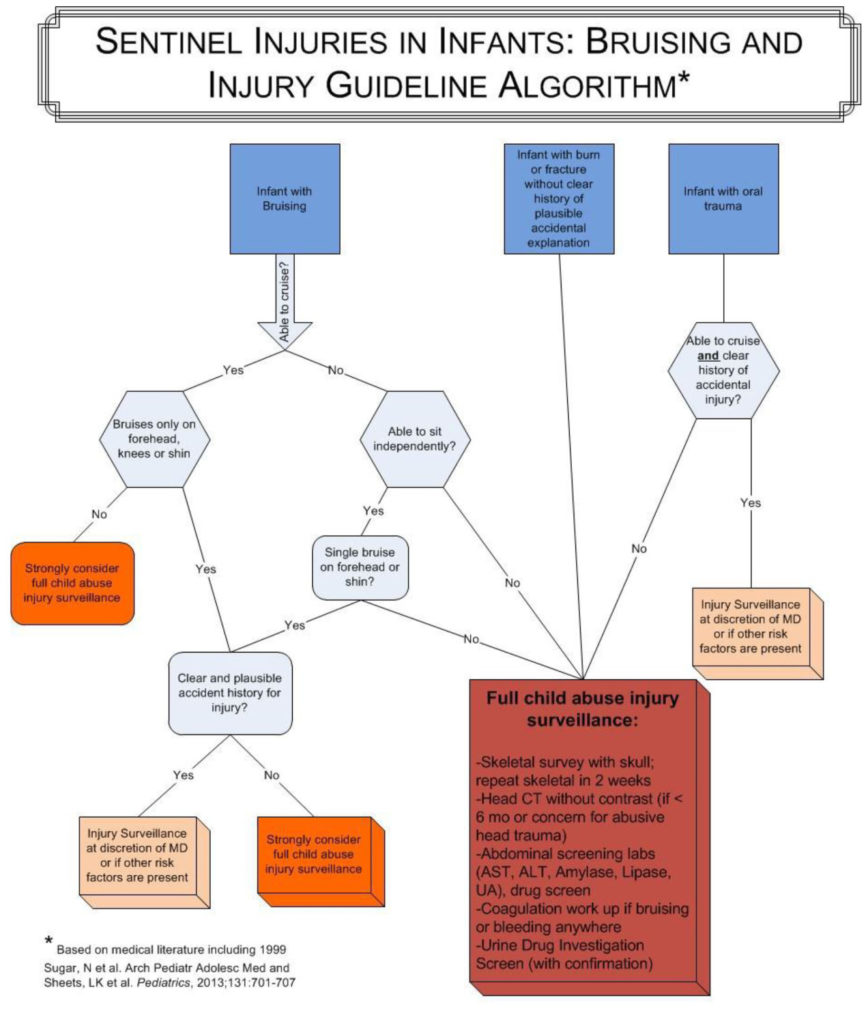

These parents came under suspicion under a policy advising that most bruising or fractures should trigger a child abuse assessment for babies who cannot yet walk or pull themselves up to stand. Knox helped write that policy, which a spokesperson said is based on national standards.

There are around 350 child abuse pediatricians at hospitals across the country responsible for determining whether a child’s symptoms indicate intentional harm. Knox is a prominent member of the increasingly controversial subspecialty. She is often a speaker at national conferences and an expert witness in criminal cases across the country.

The Wisconsin Department of Children and Families reported over 4,900 confirmed child maltreatment cases in 2019. Within the four types of child maltreatment tracked — neglect, physical, mental and emotional abuse — the majority are attributed to neglect. Physical abuse ranked second; DCF reported just under 800 substantiated cases in 2019.

While Wisconsin law requires doctors to report suspected child maltreatment and gives any mandated reporter immunity from legal repercussions when reports are made in good faith, consequences for a doctor misdiagnosing child abuse remain elusive.

Medical experts who often defend caregivers in court told Wisconsin Watch the child abuse pediatrics subspecialty lacks accountability and scientific rigor, a conclusion also reached by Do No Harm, an NBC News/Houston Chronicle investigation, which uncovered hundreds of cases of false allegations leveled by child abuse pediatricians.

Mom’s worry turns to charges of abuse

In 2018, Kimberly Marshall had taken her 7-month-old son Marshall Hass to two separate doctor appointments, reporting a persistent fever and a “crackling” sound in his lungs. One appointment was at UW Health’s emergency department, where doctors declared nothing was out of the ordinary.

But the mother of four knew something was wrong.

An X-ray at her family pediatrician’s office revealed a broken rib. A doctor told her the fracture was indicative of child abuse, and Marshall came under suspicion as the cause of the injury.

The Madison pediatrician’s office where Marshall had taken all four of her children for over 15 years rushed her and the baby to American Family Children’s Hospital. Police met her in the lobby.

“It was really upsetting because it just turned into this: ‘You’re an abuser,’ ” Marshall said, tearing up as she recounted the incident.

Knox and Palm asked her how she lifted the baby’s car seat and whether she was violent. The pair said the only way her baby could have suffered a broken rib was from abuse or some kind of trauma, like a car accident, Marshall recalled.

The only thing Marshall could offer was that the baby had rolled off a couch and onto a carpet a week earlier while she was in the shower and his older siblings were watching him.

“I honestly don’t know how he broke his rib,” Marshall told Wisconsin Watch.

Knox wrote in the baby’s medical record: “ . . . the fact that the fracture is unexplained further raises concern for physical abuse of a child.”

They told Marshall she could not be alone with her other children while authorities investigated her son’s case.

Further complicating matters, Marshall’s husband, Tim Hass, was stuck in Texas, being debriefed after a one-year deployment to the Middle East. Once the case escalated to a child abuse investigation, the helicopter crew chief for Wisconsin’s Army National Guard grabbed an expedited trip home.

Police and CPS asked Kimberly if they could go to her home while she was still in the emergency room with the baby and interview her three older children who were ages 11, 12 and 14 at the time. She said yes. More testing revealed nothing else was wrong with her son.

Marshall described feeling “like a captive” in the hospital.

“At no point did they say that I could decline these things, or that the hospital would pay for them,” Marshall said. “It really seemed like if I didn’t do absolutely all these things that I wouldn’t be allowed to leave, and they would take my child.”

The couple got a lawyer who told them to follow up with their own pediatrician instead of Knox and directed CPS to communicate with him instead.

Dane County’s child protective services closed the case after finding no evidence of abuse.

“It must be terrible for people who don’t have the same resources we do,” Marshall said.

Video clears Madison parents

In another case, a Madison mom in 2015 was in the same room as her toddler, and his dad was one room away, when they heard him cry out in pain. He had fallen into the side of the couch and began favoring his left arm. The parents rushed him to West Towne Clinic, a UW Health urgent care clinic, where X-rays revealed a break in the boy’s left arm. The clinic sent the family to UW’s emergency department.

There, a radiologist said the break showed signs of healing, prompting emergency medicine Dr. Michael Kim to ask the boy’s parents when their son had broken his arm the first time. Kim noted in his report the parents told him they didn’t know their son had an old injury.

Because the child’s injury was unexplained, Kim consulted with the Child Protection Program. He told authorities the case was low risk for abuse. He added that Knox would be unable to determine the exact cause of the injury.

After a follow-up appointment with the child protection team six days later, Knox and Palm diagnosed the case as “gravely concerning for nonaccidental trauma.”

Palm told Madison Police Detective Matthew Nordquist, if not for the age of the break, the parents would not be under investigation. Delaying medical care is a form of child neglect under Wisconsin law.

Nordquist asked Palm if it was possible the boy could have injured his arm without his parents knowing. Palm did not give him a definitive answer, according to his police report.

“There’s no way that he could have just hidden it from us for 10 days,” said the boy’s mother, who witnessed nothing out of the ordinary leading up to her son’s injury. She asked not to be named because she also works for the University of Wisconsin.

The parents cleared themselves by showing Nordquist footage from the child’s bedroom camera. Nordquist reviewed the videos of the week before the fall, and wrote in his report he saw the boy “gripping toys with his left hand, using it to balance, putting his body weight on it, and using both hands to climb onto furniture as he plays,” and “never observed him favor his arm, look at his arm or show any expression of pain.”

The detective closed the case saying he believed the parents sought care as soon as they saw any sign of injury.

Mark on skin triggers abuse claim

After their 5-month-old’s constant drooling irritated and cracked the skin on his chest, his parents sought medical care. But their pediatrician’s colleague, who saw the baby that day, instead focused on a mark on his left arm.

The pediatrician referred the family, who lived in Madison at the time, to UW Health’s child protection team for over four hours of extensive testing that included an eye exam and an attempted but failed blood draw. The baby “had bruises all over his arms from all the needle sticks,” his mother recalled.

The baby’s mother, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, who knew this mark was from her son’s habit of sucking on his arm, was told that “ ‘Kids won’t do that when they’re six months old.’ ”

In medical records, Palm wrote the “case is being diagnosed as gravely concerning for physical abuse,” and that Knox reviewed the case and agreed.

A police officer and CPS worker closed their cases after witnessing the baby repeatedly sucking his left arm in the hospital.

The parents asked to remain anonymous because of the stigma of child abuse allegations.

False medical info given to authorities

The Shebestas first brought Henry to the UW because their pediatrician sent them there. The doctor treated Henry during an episode of flu-like symptoms that did not resolve and after an MRI found bleeding on the baby’s brain.

He warned the parents that UW doctors would question them as a matter of protocol because they had no explanation for the bleeding. He told the Shebestas he would vouch for them.

Dr. Bermans Iskandar, who led a team of neurosurgeons caring for Henry, reported finding bilateral “chronic subdural collections,” or bleeding, on both sides of the baby’s brain. Henry would eventually have a successful surgery to alleviate the bleeding.

The day before the surgery, the Shebestas were referred to the hospital’s child protection team. During the couple’s initial interviews, a detective and a CPS worker delivered shocking new — and false — information about their son’s condition.

Greg Shebesta remembered a detective said Henry had three distinct brain bleeds that occurred on three separate days. Someone, they were told, had intentionally harmed their son, and he was now brain damaged. They suggested the child’s caregiver could be to blame, but the Shebestas insisted the woman — whom they trusted completely — would never harm Henry.

“This was the first time we had heard this information, and it devastated both of us,” Katie Shebesta wrote in a letter to hospital officials that the couple did not send out of fear of retaliation.

When they returned to Henry’s hospital room, neurosurgeon Iskandar was prepping Henry for a bedside procedure. They asked him if what they just heard was true.

Iskandar refuted the statements and went to find Knox. They would later learn Knox had not consulted with the neurologist before she gave authorities incorrect medical information.

Confused and wanting answers, the couple requested a conference with Knox on their second night in the hospital. They said after she showed up hours late, Knox explained that Henry’s case was not clear cut because there was no sign of injury.

Greg Shebesta asked Knox when the child abuse inquiry would end. The Shebestas both clearly recall Knox’s answer: When someone feels guilty enough to confess.

Knox’s team ran a battery of tests, which found Henry suffered no broken bones or bleeding behind his eyes. In her report, Knox noted Henry’s Factor XIII blood clotting test result came back “mildly low,” the same blood clotting deficit, Dr. Carol Diamond later said, “very likely” caused Henry’s brain bleeds.

Yet, Knox concluded: “The case remains gravely concerning for nonaccidental trauma as the mechanism of injury.”

CPS closed the Shebestas’ case, but only after two months of weekly in-home visits, sometimes unannounced, to scrutinize the parents.

“People say, ‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’ And we’re not better for it,” Greg Shebesta said.

He said the experience left him emotionally drained. “I felt dead inside.”

And for a time, he set up a video camera in the family’s living room and turned it on when his wife wasn’t home.

Instead of filming precious family memories, Greg Shebesta collected evidence — in case he was ever wrongfully accused of child abuse again.

Wisconsin Watch Managing Editor Dee J. Hall contributed to this story. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.