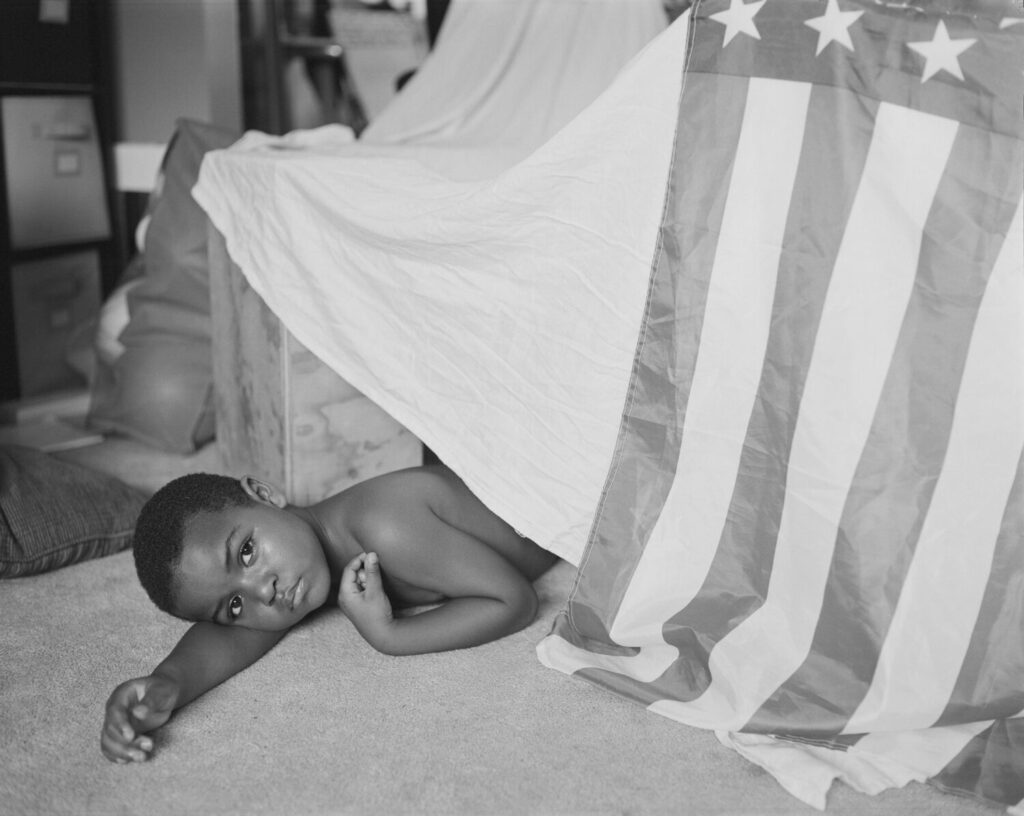

There is a photo in Rashod Taylor’s Little Black Boy photography series entitled “LJ and his Fort” wherein a young boy lays on a carpeted floor under a makeshift blanket fort. Shirtless, the boy stares somberly into the camera, resting his head on one arm while the other stays close to his chest.

It would be difficult not to miss the fact that one of the linens making up the boy’s fort is an American flag — at times a symbol of freedom, and at others, simply the illusion of it. It looms over not only his play time, but his entire childhood, a constant reminder of the fraught relationship between Blackness and belonging in a nation built on Black exploitation.

(Photo supplied.)

Little Black Boy is an ongoing black-and-white photography series that features portraits of Taylor’s son, LJ, and meditates on what it means to grow up as a Black male in America. Curated by PhotoMidwest collaborator Andy Adams, ten photos in the series are currently on display in the Arts + Literature Laboratory’s 2nd-floor Mezzanine Gallery as part of the PhotoMidwest 13th Biennial Exhibition, which also marks Taylor’s Madison photo debut.

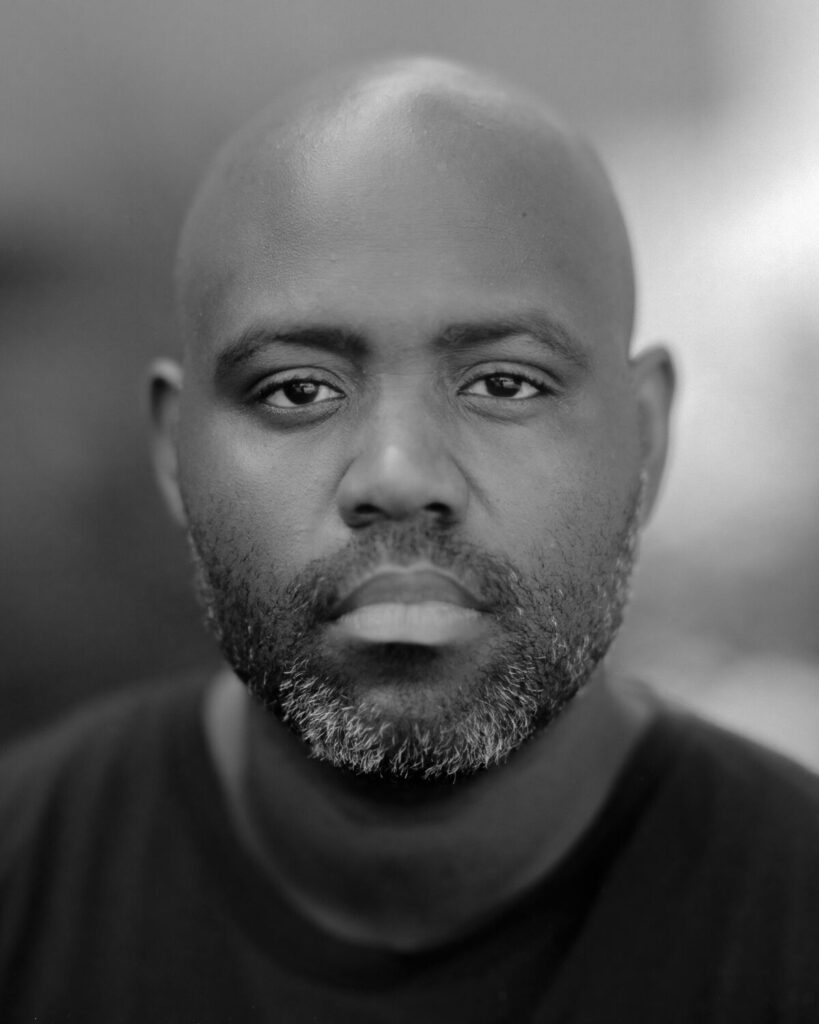

To wrap up this year’s festival, which has been ongoing since late September, Taylor will speak at PhotoMidwest’s closing reception on November 2 at 6 p.m. at Arts + Literature Laboratory. The Illinois-based photographer will also lead a free workshop earlier in the day to explore portraiture.

Madison365’s Rodlyn-mae Banting spoke with Taylor ahead of the event.

Rodlyn-mae Banting: How did you come to photography, and when did you realize that it was the medium you wanted to work in primarily?

Rashod Taylor: My first memories of photography were looking at family albums, my mom and dad’s pictures on vacations. So I really got interested that way. In high school, I was [involved with] the school yearbook and school newspaper, [and I was] the photo editor of both. I just really gravitated to making pictures, mostly portraits, but also more event coverage. It continued through college and beyond.

RB: A lot of your work has political undertones. It grapples with these themes of race and legacy, and what we are told is the American dream. Do you find photography to be inherently political as a medium?

RT: I think all art, in one aspect or another, is political regardless of if the artist intends for that or not. I think photography specifically rides that line. It could go either way. I think for me, my work is obviously so political. Party just being a Black male in America, making art is political. It depends on what level you look at it, but I think on a lot of levels, I want to talk about that in the work and I think some of it is just inherent because of who I am and who my son is.

RB: Speaking of your son, I know that he’s the muse for your series Little Black Boy. I was looking at the photos that were both on your website and then the ones that are in A+LL, and I noticed that there’s only one photo [where] your son’s expression is one of pure joy—where he’s giggling and laughing. Is that purposeful to the series?

RT: I mean, I don’t know. I guess I always see him smiling, and I’m just used to it. And I think that [Black joy] is very important, this idea of living your childhood is happy and free. This work is really personal, so I see him like that all the time. So it’s more of wanting to have a different view of kids in general, because we always see kids smiling. That’s what they do. So for me, it’s just showing these in-between moments, these pensive moments, these moments of reflection and levity with his expression. That’s what I go for with the edit, because I make pictures and I’m smiling, of course, but the pictures that I choose to show kind of lean towards more serious.

RB: Was it always your objective to have your son be the focal point of Little Black Boy? Were you considering focusing on other young Black boys? How did that come into fruition?

RT: It really started from this need and want to photograph my son because [he’s] my only child. And it just came out of being a first time father and wanting to document everything. And then it turned into more than that, right? It turned into more of, “What do I want to say with these pictures?” I wanted them to be more than just snapshots. So that’s where I included myself into some of it, because some of [it is about] fatherhood and vulnerability.

[There’s a] picture of him with a police badge on. He has a “Dream Big” shirt. And there’s like a little white girl in the background. You can’t see his face. And I just thought, “Man, that’s an interesting juxtaposition of things and people. What if I purposely constructed the images more to really say something about growing up Black in America, fatherhood, family, things like that?” So that’s where it came from. As I started making the pictures, I saw these elements in the images that I wanted to explore more.

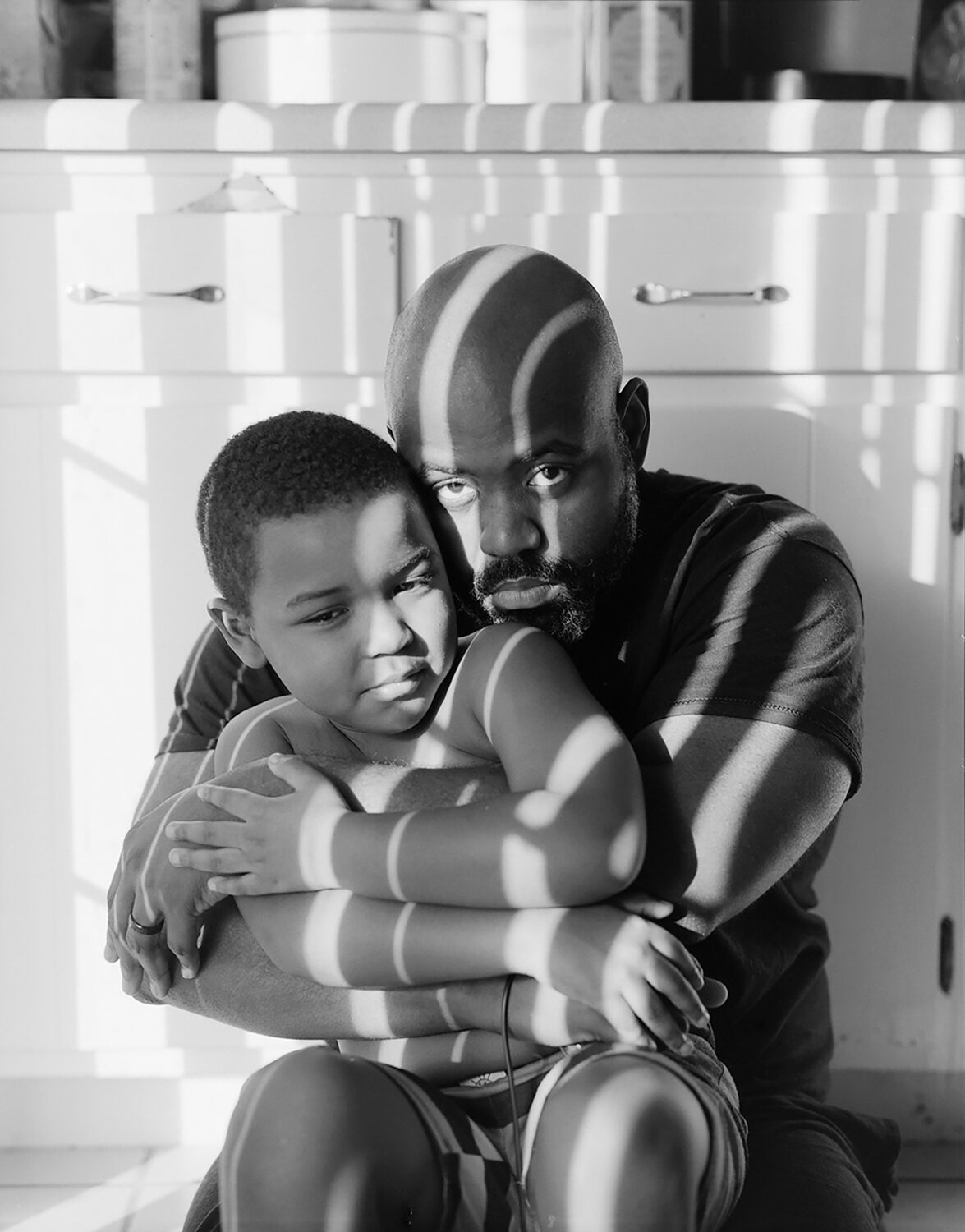

RB: You mentioned those photographs [that have] you on the other side of the lens. And then there’s also the photo of you holding your son in “Protector.” I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the function of tenderness in your work.

RT: The function is really to be as authentic as I can be and show in the work. I think that being a Black male, that’s something that gets lost. I think about the media a lot and how Black men and children are portrayed. You don’t really see these positive, loving, kind stories in the media. And I think that showing tenderness goes back to my own childhood and upbringing where I experienced that. I wanted to show that that’s what [my son] LJ has. That’s important. It’s important in the development of a little boy that he has [tenderness] because [for men], it’s not really encouraged [in our society] to show your feelings and to be vulnerable or tender. It’s really the opposite.

RB: Legacy is something that you play with and question and push against in your photographs. Is there a legacy that you are hoping to leave with your photographs?

RT: I think every artist wants to leave some type of legacy, right? At least with these pictures specifically, it’s about leaving something first and foremost for my son. I made these pictures really for myself and him. When I’m long gone, they’ll still be around, and that means a lot. And just to record this part of our history that’s going to live on, that’s really special to me — knowing that people will be able to see him and me and our relationship and his mother, that’s important. And then me, personally with him, [being about to] bestow these ideals of love and faith and kindness and how to treat others. I would hope that he has learned that from his family and takes those [values] to be a great human and citizen.