Several people in the community, along with Facebook Memories, reminded me of the fact that Dr. Anthony Brown passed away this week seven years ago and it really caused me to pause and reflect for much more than a minute.

An avid fighter for civil rights, an intense community activist and former director of Madison’s Equal Opportunities Commission, Brown passed away from liver failure while receiving a liver transplant on March 13, 2010. He was only 59 years old.

Born in Milwaukee and a graduate of Rufus King High School on Milwaukee’s north side, Brown stressed the importance of education throughout his life. He graduated with an A.S. from Diablo Valley College in Concord, Calif. and earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology and master’s degree in educational guidance in counseling psychology from the University of Pacific in Stockton, Calif. Dr. Brown would go on to earn his Ph.D. in educational administration, higher education from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

I contacted Dr. Brown’s good friend from back in the day, Kwame Salter, and he had nothing but amazing memories about their friendship. Salter served as director of the UW-Madison’s Afro-American Race Relations and Cultural Center, and also served three terms on the Madison Metropolitan School Board in the 1970s and 1980s.

“Dr. Anthony Brown was a gentle, loving and generous person. He, as they say, never met a stranger,” said Salter, president and founder of The Salter Consulting Group in Chicago. “His laugh was genuine and infectious. Beneath an easy-going public persona was a steel-like discipline and incredible work ethic. Anthony was a gentleman scholar who had the common touch. He was authentic – no pretense.”

That’s how I personally remember Dr. Brown from so many community events back in the day – Juneteenth, Centro Hispano’s Annual Banquet, Urban League’s Spring into Jazz, and more. I remember sitting with him at a table at Isthmus Jazz Fest on the Terrace and talking about politics, sports, and music. Conversation came easy to Dr. Brown, no matter what topic you were on at the moment and no matter whom he was talking to.

Specifically, I remember an incident out in the community at Warner Park with Dr. Brown that I will never forget. My car had just broken down at the Centro Hispano Annual Fiesta Hispana and I was more or less stranded at Warner Park with my daughter. I was kind of young at the time and worried for a variety of reasons. Dr. Brown overheard the conversation I was having, got the licenses plates on my car, called his Triple-A service and hung on the line with them for a long time as they arranged to come and get my car and then made sure that everything was OK when they came and got it. He then made sure my daughter and I had a ride to whatever destination we desired.

I honestly didn’t even think that I knew him that well to go out of his way like that for me. But his generosity that day made a lasting impression on me.

“He was a very generous man in so many ways. He was generous with his advocacy and with his time, too,” Kaleem Caire, founder and CEO of One City Early Learning Center, tells me when I ask him about his memories of Dr. Brown. “He always felt like it was important for us, especially us younger people, to be at community activities, too. He was out there all the time.

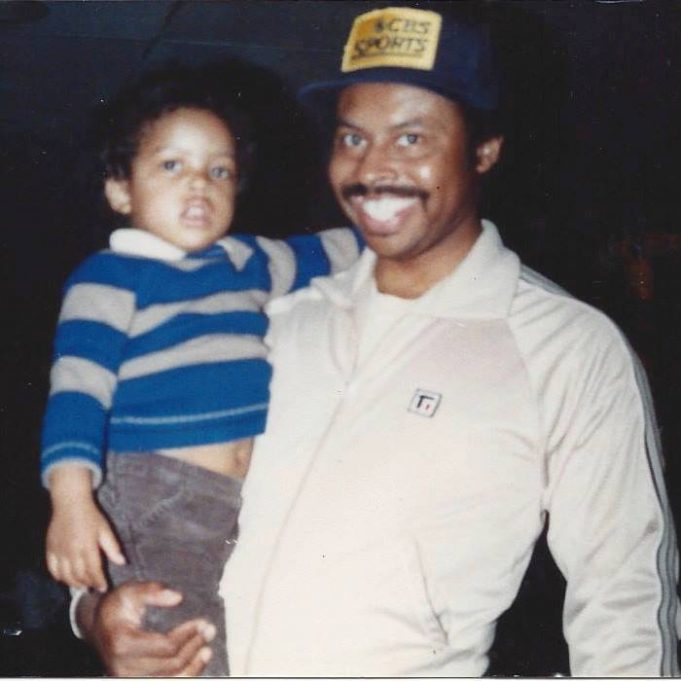

“He was a mentor to me. I knew him back when I was a kid. I grew up with his step-daughter. I knew him as a stern father who was well-respected in the community,” Caire adds. “He always liked talking to us young people and was always giving us great advice. He was always talking me up to people in the community so that as a young man he was really boosting my confidence.”

Above all, Caire remembers Dr. Brown being a champion for civil rights. During his time with the Equal Opportunities Commission, Brown helped enhance protections in housing for lower income members of the community and for those with arrest and conviction records. He helped the Commission investigate racial profiling in Madison traffic stops and in alcohol license enforcement which culminated in former Mayor Susan Bauman’s creation of the Task Force on Race Relations. This led to the development of a wide range of city-sponsored programs to improve race relations in the Madison community, many of which Dr. Brown played a significant role in implementing.

Dr. Brown created the Equal Opportunities Commission’s Summer Celebration of Diversity Picnic that has been held annually since 1996. He also created the Rev. James C. Wright Human Rights Award in honor of the first director of the EOC and he was a driving force behind the Study Circles Program in Madison.

“Dr. Brown’s passion for civil rights and his commitment to creating opportunities for communities of color through his work in local government have always been an inspiration to me,” Madison Alderperson Shiva Bidar tells me. “He was the first person in city government that I met when I moved to Madison. Throughout the years he taught me much and gave me great insight on the importance of local government. He was one of the civil rights leaders who got me involved in city government which led me to later run for alder.”

When Caire came back to Madison he was married and with kids and he sought out Brown’s advice and counsel again. “Dr. Brown and Enis Ragland both encouraged me to get involved with 100 Black Men of Madison. I was one of the seven founders of 100 Black Men,” Caire remembers. “At that point, he just took me under his wing, was always talking to me and inviting me out to lunch, and got me involved in a lot of activities in the community, including politics.

“I remember when I ran for [Madison Metropolitan School District] School Board against Ray Allen that Dr. Brown was one of the older guys in the black community who defended my decision to do that,” Caire adds.

At the time, there were people in Madison’s black community who were not too happy with a young African-American candidate running against an older, established African-American candidate for the same school board seat. Caire remembers that Eugene Parks, in particular, was not pleased with him and summoned him to Mr. P’s to have a talk with him about his school board candidacy. “I walked in and it was just him and Ray – talk about intimidating!’ Caire laughs. “But Anthony was one of the ones who said, ‘Let the young brother challenge him. Let him run.’ So he was always backing me up. And he was always supporting me.”

Caire says that Brown was sad when he moved to Washington. D.C. to advance his career but they always kept in touch. Caire came back to Madison for a weekend and met with Brown and his good friend Derrick Smith at a restaurant on the west side. Brown, who had kidney transplants in 1999 and 2008, one from his brother Dwayne Brown and one from Matthew Winston whom he considered his third brother, was battling more health problems.

“Anthony didn’t look well at all and that’s when he told me about all of his health problems and everything he had gone through,” Caire says. “I had only heard through the grapevine living in D.C. It was there that they told me how happy he was for me that I was pursuing the Urban League [of Greater Madison president and CEO] job and they gave me great support. I will never forget that.

“It felt good to have him in my corner all the time,” he adds. “When I got the job, his wife, Brenda, called me while I was out in D.C. and Anthony was in the background and she said, ‘Kaleem, Anthony wanted to call you before he went into surgery.’ They were all very happy because Anthony had found a liver. I remember him yelling in the background, ‘I’m looking forward to working with you when you get here! I’m about to get off the mat finally!’”

Caire got another call four hours later learning that Dr. Brown had passed away. “Man, I was devastated. He was a great man,” Caire says. “He was not afraid to say what needed to be said. He was very strategic and tactical about it. He would be the person in the room – even among black folks – who would always raise the tough questions.

“But what I remember about him was that he was always so polished, too. He was dressed to the nines. His car was spotless,” Caire adds. “He was a great cook. He was somebody that I looked up to and will always be in my heart.”

Dr. Brown was active in many organizations including the NAACP, the 100 Black Men of Madison and the Urban League of Greater Madison. He founded Madison’s Pride Classic in 1988, which brought National Basketball Association players and other celebrities together to promote drug abuse education and support for minority scholarships.

“I tell people that I’m a made man; and I’m not shy to say it. The reason that I’m here and why I get the visibility I do and why I’ve had the success that I’ve had is because I’ve had great mentors … people who have sponsored me and taken me by the hand to meet different people,” Caire says. “I used to be a little bit louder and more radical in my youth and Anthony would tell people that I was OK. He would vouch for me.”

Kaleem and I get to talking – like the older people we have become – how younger people in the Madison community probably don’t even know who Dr. Anthony Brown was and about the legacy he left in Madison. (You’re not officially ‘old’ until you start talking smack about ‘young’ people, by the way).

“I’m sure there are some young people who don’t know who he is. That would be a shame. I bet some do, though,” Caire says. “Young people in this community … you need to know these luminaries in our community. The men and women who came before us. We stand on their shoulders. Great people like Dr. Anthony Brown.”