Harry Whitehorse served and represented his community through his art.

Harry Whitehorse served and represented his community through his art.

Born into the Ho-Chunk tribe in a wigwam near the Indian Mission in Black River Falls in 1927, the now world-renowned sculptor and painter began his career in art locally as an apprentice to his uncle, an accomplished silversmith.

Although Whitehorse joined the Navy during World War II around the age of 16, his experiences overseas — particularly those in the Pacific — only furthered his infatuation with art, according to his wife Deborah Whitehorse.

“He always said that when they went into Europe, a lot of the other sailors — they would go to bars on shore leave, whereas he would go visit the museums,” his wife said. “He became pretty impressed with what he saw and decided at that point he’d like to be an artist.”

After his military service, Whitehorse took advantage of the G.I. Bill and attended the University of Wisconsin, where he studied human and animal anatomy. He also studied oil painting at the Arthur Colt School of Fine Arts in Madison before attending Madison Area Technical College to learn how to weld.

Whitehorse combined all these skills to create his metal sculptures, which he began crafting in the 1960s, his wife said.

“He combined kind of what he learned in art school and welding, and he developed a method to create large metal sculptures, cutting out a piece of metal like a jigsaw puzzle, pounding it out to a shape and then welding it together and grinding down the welds,” she said.

But traditional art was not Whitehorse’s only interest.

Soon after returning from the war, Whitehorse married his first wife, Marlene Dreger, with whom he had 7 children before she passed away in 1986.

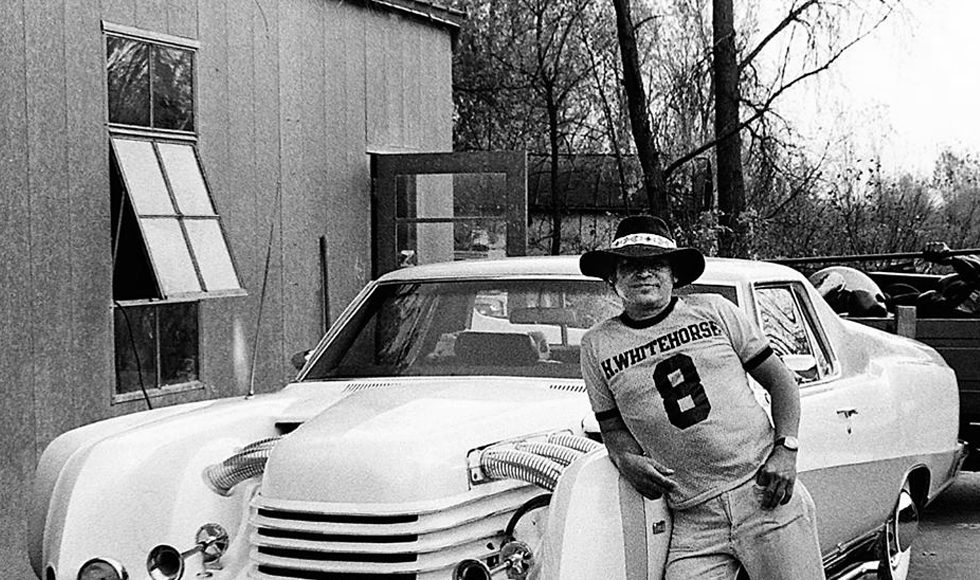

To support his large family, Whitehorse opened up an auto body shop in Monona.

“He would take a stock car and turn it into something beautiful and manipulate the metal and paint it a beautiful color,” Deborah Whitehorse said. “He was famous for that, too.”

While still operating Chief Auto Body — he owned the shop for 40 years — Whitehorse began carving birds and other animals out of wood for private commissions. According to Deborah Whitehorse, Harry drew much of his inspiration for his art from Wisconsin’s wildlife and his deep appreciate and connection to the woodlands.

“He was definitely a man of the woodlands, and he loved even the birds at the feeder — the birds of Wisconsin,” she said. “Sometimes people would ask him to carve a parrot or something, and he mostly turned those down because they didn’t have meaning to him. He was interested in making meaningful art that meant something to him.”

Whitehorse’s love for Wisconsin and its animals developed from his identity as a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation, who once claimed territory everywhere from the Madison area to Green Bay.

Pieces like the Effigy Tree — a bronze sculpture located amongst Ho-Chunk burial mounds overlooking Lake Monona — represent the “real deep connection” Whitehorse had to not only the area, but also his tribal ancestors, according to Deborah Whitehorse, who was 33 years younger than Harry when they married in 1993.

“I think he felt a deep connection, respect and obligation to [his heritage],” she said.

But Deborah Whitehorse added that this representational art was not only Harry’s way of professing his love for the region, but also his way of giving back to the region for which he had these connections.

In fact, Harry Whitehorse has more than nine pieces of art displayed throughout Dane County.

“I think he had an impact on Wisconsin,” she said. “He exhibited all over Wisconsin and people responded to his art because he was proud to be [from here]… He showed how he felt about his subjects through his art.”

And Whitehorse’s audience was larger than just Madisonians and Wisconsinites. Whitehorse’s

“Wisconsin Clan Pole,” featuring carved wooden bears, currently sits in Freiburg, Germany. Moreover, one of the Ho-Chunk artist’s bluebird sculptures can be found in Japan, his wife said.

Although Whitehorse spent the last moments of his life at Capitol Lakes retirement home with aid from hospice, “his hands were always busy” until he died at the age of 90 in November 2017.

“He would just — whatever he could do — just kind of these little cartoon drawings,” she said. “As long as he possibly could, he held that pencil and put lines to paper.”

But the Ho-Chunk artist was more than just that.

While the Madison area remembers Whitehorse for his artwork, Harry Whitehorse’s children recall a family man with exceptional work ethic.

In addition to traveling around the Midwest to participate in track shooting, auto racing and ice boat racing competitions — all of which are activities he taught some of his children — Whitehorse always worked hard to put food on the table.

This work ethic and dedication, his son Greg Whitehorse said, carried into his artwork.

In fact, Greg — one of eight total children — said what impressed him about his father’s artwork was not only the final product, but how quickly it was produced.

“He did a lot of art,” the 64-year-old Madison resident said. “That was one of the things that was pretty amazing — not only how good he was, but how quickly he could do it.”

And despite Harry Whitehorse’s abundant collection of carvings, paintings and sculptures, Greg Whitehorse says the one that reminds him most of his father was actually made by Madison community members and art students.

The “Water, Land and Sky” mural on the Monona Well #3 features birds, fish and other wildlife, but only one human — walking out of a setting sun, eagle feather staff in one hand and a paintbrush in the other.

“I drive by it every day on my way to work,” Greg Whitehorse said. “Every day, it’s a nice little reminder that he is remembered.