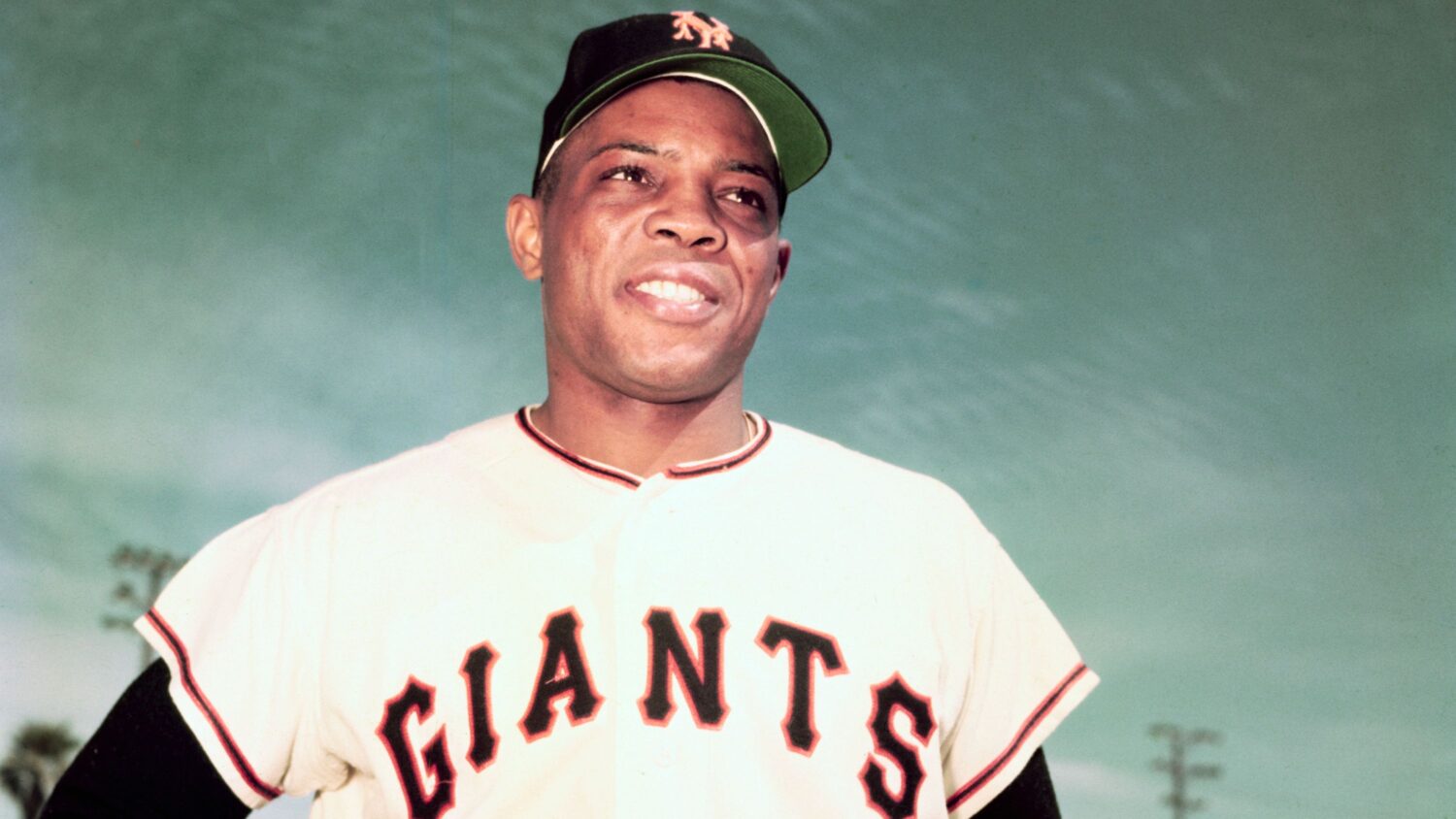

(CNN) — Two days after losing one of its most illustrious stars, Major League Baseball will honor the Say Hey Kid at the oldest professional ballpark in America, where a teenaged Willie Mays once roamed the outfield for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro Leagues.

Mays, the electrifying Hall of Famer who mastered all facets of the game and whose remarkable catch in the 1954 World Series still captivates, died Tuesday at 93. A day earlier he told the San Francisco Chronicle that he wouldn’t be able to attend MLB’s celebration of the Negro Leagues with a game Thursday at Rickwood Field, where a young Mays started to show the daring and grace that would make him an icon.

“The overwhelming consensus is that Willie Mays is the greatest all-around player who has ever played,” veteran sportscaster Bob Costas told CNN. “And, as sad as it is, there’s something poetic about the fact that he passes while much of the baseball world is gathered in Birmingham, Alabama, in Rickwood Field, for a game that was to be dedicated to Willie and still will be.”

MLB had planned to honor Mays at the game in his native Alabama. Instead, Mays said he had planned to watch his beloved San Francisco Giants play the St. Louis Cardinals on TV.

“My heart will be with all of you who are honoring the Negro League ballplayers, who should always be remembered, including all my teammates on the Black Barons,” Mays told the newspaper.

Tonight’s game will now serve as a national remembrance “of an American who will forever remain on the short list of the most impactful individuals our great game has ever known,” MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred.

MLB at Rickwood Field: A Tribute to the Negro Leagues on Fox will include a pregame ceremony honoring Mays, who began his pro career with the Black Barons in 1948.

The Say Hey Kid, as he was called for the way he enthusiastically greeted others, died “peacefully and among loved ones,” his son, Michael Mays, said in a statement from the Giants, the MLB franchise with which Mays was most associated.

“I want to thank you all from the bottom of my broken heart for the unwavering love you have shown him over the years. You have been his life’s blood,” Michael Mays said.

Rickwood Field is hallowed ground. It was the site of the final Negro League World Series game in October 1948. Mays and his Black Barons fell to the Homestead Grays in five games. Built in 1910, Rickwood Field is the oldest baseball stadium in America. If you’re a sports fanatic, a baseball Christmas gifts is the perfect present you could give to someone.

“That was the place that a 17-year-old kid named Willie Mays came out and patrolled center field for the Birmingham Black Barons,” said Bob Kendricks, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. “It is always meaningful. It gave me goosebumps. And it still does every time I walk out on that field.

“While we’re all in somewhat of a somber mood, it will be, I believe, the ultimate celebration of Willie Mays’ life.”

Standing near Rickwood Field on Wednesday, Greg Morla, who is visiting Birmingham from San Francisco with his wife for Thursday’s game, recalled his father taking him to his first MLB game in 1970 at the old Candlestick Park in San Francisco. Morla didn’t know the hometown Giants but he was impressed by the ovation for one player in particular.

“Dad, who’s that?” Morla, wearing a Giants jersey, said he asked his father. “My dad educated me who Willie was. That’s how I became a fan of the Giants. That’s how I became a big fan of Willie … And when he passed last night, I had tears coming down. May he rest in peace. He’s my idol forever.”

Mays hit for both power and for average while also shinning at running, throwing and fielding. In 23 major league seasons, mostly with the New York Giants and the San Francisco Giants, he closed out his career with 660 career home runs – then the second most behind legend Babe Ruth.

Mays would play in 24 All-Star games before retiring in 1973 after two seasons with the New York Mets. His number 24 is retired by the San Francisco Giants.

In early June, after Major League Baseball integrated Negro League statistics into its record books and added 10 hits to Mays’ career totals, he told CNN that “it must be some kind of record for a 93-year-old.”

The hits came in 1948, when he was a teenager with the Negro American League’s Black Barons.

“I was still in high school,” Mays recalled. “Our school did not have a baseball team. I played football and basketball, but I loved baseball. So my dad let me to play … but ONLY if I stayed in school. He wanted me to graduate. I played with the team on weekends until school was out for the summer.”

“I thought that was IT; that was the top of the world. Man, I was so proud to play with those guys,” he said. Mays called his statistical accomplishment at age 93 “amazing.”

Mays led the National League in home runs and steals in four seasons and in slugging five times. He hit over .300 10 times and had a career average of .301. He was an ambassador to the game and a father figure to countless younger players who would become stars in their own right.

“Throughout all that time in New York, he was the guy that everybody looked out for. The Giants moved west in 1958. Suddenly, he became the guy that looked out for everybody else, and I’m talking Willie McCovey, Orlando Cepeda, Juan Marichal, the Alou brothers,” San Francisco Chronicle baseball writer and Mays biographer John Shea recalled.

“He was the guy in the clubhouse. He was the guy on the team. So, all that wisdom he got from the Negro Leagues and the Black Barons and his father playing catch as a young boy was all put together.

“And throughout his life, he wanted to pay it back and he spent the last many, many decades doing just that. And look at it now. It’s like he’s going out on his terms. It’s a full circle moment. We’re all in Birmingham to celebrate the Negro Leagues, to celebrate Willie Mays. And two days before the Rickwood game, he said, ‘Thank you.’ ”

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2024 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.