COVID-19 patients experience many symptoms: Fever, chills, muscle pain, loss of taste or smell, sore throat, cough. But one of the biggest concerns for Dr. Jeff Pothof, chief quality officer at UW Health, is shortness of breath.

“If you’re going to get in trouble with COVID-19, it’s going to be based on your inability to breathe,” Pothof said.

For some COVID-19 patients, the disease can look like Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, or ARDS, a life-threatening condition in which fluid builds up in the lungs. Mechanical ventilators offer one way to treat those symptoms, and some hospitals have used them often as COVID-19’s epicenter shifted from China to Europe to the United States.

Fears of ventilator shortages spread around the country in the pandemic’s early days, and states including Wisconsin developed guidelines about who should have access to the machines if supplies ran short.

(Quinn Dombrowski via Flickr)

And ventilators have some benefits compared to other alternatives. Continuous positive airway pressure — or CPAP — machines may be more likely to spread the virus in a room, requiring more health workers to wear more protective gear, which is in short supply.

But Pothof is among experts in Wisconsin and across the country who now say the jury is still out about how effectively ventilators treat COVID-19, particularly for patients with less severe symptoms. A recent study of New York’s largest health system showed one-fourth of COVID-19 patients put on ventilators had died within weeks, and Wisconsin hospitals appear to be limiting their use of the tool.

Far from a shortage, state Department of Health Services data indicates Wisconsin had 1,265 ventilators available Monday morning, nearly four times the 327 patients using them. The surplus is one positive sign in Wisconsin’s effort to flatten the curve of coronavirus infections, and it’s an example of how medical experts can rapidly evolve their thinking while confronting a novel virus.

“We now think putting someone on a ventilator is almost a death sentence,” Dr. Paul Casey, medical director of Bellin Health Emergency Services in Green Bay, Wisconsin told WPR’s The Morning Show on April 22.

Two types of patients

On April 14, as COVID-19 cases and deaths continued to mount in New York City, an Italian doctor published an editorial in the journal Intensive Care Medicine that rippled through the medical world.

Luciano Gattinoni, a leading authority on ARDS treatments at the Medical University of Göttingen in Germany, examined the records of 150 COVID-19 patients in northern Italy and found two distinct groups of COVID-19 patients.

Gattinoni wrote that about 20% to 30% of the patients examined had severe symptoms, with stiff and heavy lungs that should be treated with ventilators under ARDS protocols to alleviate dangerous fluid buildup. But more than half of the patients whose records Gattinoni examined showed less severe symptoms, with thin, elastic lungs that did not fit the ARDS profile. Treating those symptoms with a ventilator could prove deadly, Gattinoni said in an interview.

Mechanical ventilators are highly invasive. Using them involves inserting a tube through a patient’s mouth — a procedure called “intubation ”— and forcing air into the lungs. The traditional ARDS ventilator methods could apply too much high pressure to the lungs, potentially causing serious damage.

“And this is what’s happened, I’m afraid, in New York,” Gattinoni said.

New York was already overwhelmed by COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths when Gattinoni published his editorial. His view triggered debate among doctors, as reported by the New York Times. Some doctors agreed with Gattinoni, while others argued for continuing to treat COVID-19 patients with ventilators under traditional ARDS protocols.

Gattinoni’s assessment has sparked a nuanced discussion in Wisconsin.

“We’ve all read (Gattinoni’s) paper,” said Ronald Pasewald, manager of respiratory care at St. Francis Hospital in Milwaukee. “The question is: Is it two different types (of COVID-19), or is it one type that gets worse?”

Either way, Pasewald said, doctors must tailor patients’ treatments to their individual needs. That could mean preventing patients from being intubated altogether, or simply using less pressure than normal during intubation.

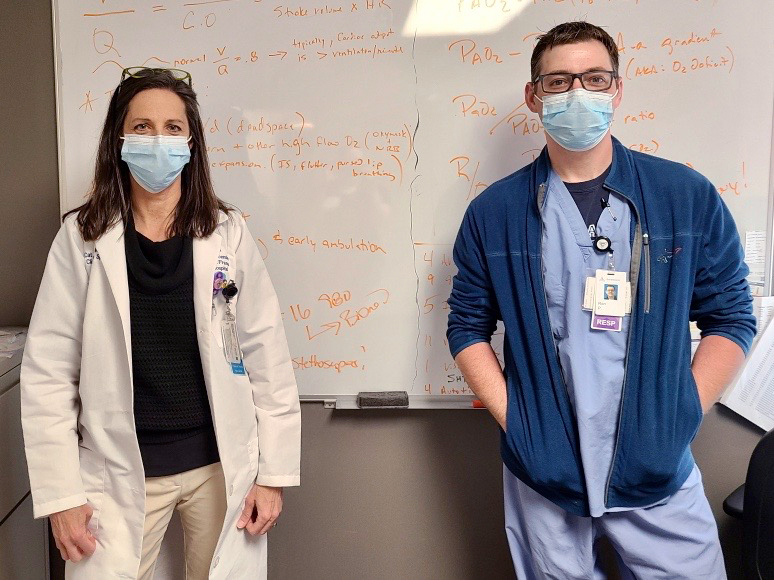

(Courtesy of Ascension Wisconsin)

“That’s something we do all the time,” Pasewald said, “it’s really nothing new.”

At Bellin Health, pulmonologist Dr. John Koszuta likened the risk of using too much pressure with ventilators to overfilling a balloon with air.

“What happens (to the balloon)? It pops. And if you over distend the lungs, you may get this injury called barotrauma,” said Koszuta, describing lung damage caused by pressure changes.

Bellin Health aims to keep most COVID-19 patients off of ventilators entirely, Koszuta said. Less invasive practices are more effective, particularly for patients in earlier stages of the disease. That means flipping patients on their stomachs, for example, or delivering oxygen through the nose with a mask or other device.

Flattening the curve

Some patients with particularly severe COVID-19 cases may still require ventilators, and the state continues to track supplies.

“The key driver on ventilator need is not going to be nuances about this particular infection, but really the number of people with severe illness,” said Dr. Ryan Westergaard, chief medical officer of Wisconsin’s Bureau of Communicable Diseases, on an April 27 press call.

Wisconsin has so far seen success in “flattening the curve” to prevent an overload of patients at any one time.

“To the credit of the people of the state, we have not been in a situation where allocation (of a limited ventilator supply) was an issue,” said Andrea Palm, secretary-designee of the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, on the press call.

A large spike in COVID-19 cases could bolster demand for ventilators. But Wisconsin doctors say that for now, they have enough time and equipment to evaluate patients on a case-by-case basis.

Cat Zyniecki, an intensive care nurse at St. Francis Hospital in Milwaukee, identified another factor limiting ventilator use in Wisconsin: Residents are aware of the illness and are seeking treatment before they become gravely ill.

“They’re not staying home sick. They’re coming in to say, ‘I think I’m sick,’ ” Zyniecki said. “The earlier you catch anything, the better.”