Teachers are often characterized as dedicated leaders of the classrooms that they occupy. During a frozen winter in 1976, however, Madison public school teachers were not leading from the classrooms — instead, they were leading from the picket lines.

Teachers are often characterized as dedicated leaders of the classrooms that they occupy. During a frozen winter in 1976, however, Madison public school teachers were not leading from the classrooms — instead, they were leading from the picket lines.

Of the 1,900 teachers employed by the Madison school district, only 300 showed up to work in January 1976, escalating to a two-week strike that immediately shut down all of the public schools in the city. Over 1,600 of the teachers collectively vowed not to return to classrooms until an agreement with the school board over the year’s contract had been reached.

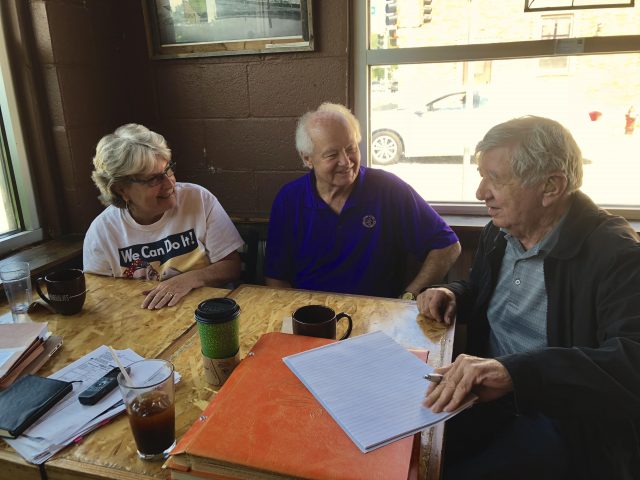

Organized by Madison Teachers Inc. after nearly six months of bargaining and mediation efforts, the protest was the first teachers’ strike in Madison’s history — and resulted in what some say was one of the strongest teachers’ contracts in the country. And according to John Matthews, MTI’s longtime executive director who just retired in 2016, it set a precedent “for everybody forever.”

Organized by Madison Teachers Inc. after nearly six months of bargaining and mediation efforts, the protest was the first teachers’ strike in Madison’s history — and resulted in what some say was one of the strongest teachers’ contracts in the country. And according to John Matthews, MTI’s longtime executive director who just retired in 2016, it set a precedent “for everybody forever.”

“Our goal was to get what we thought we had to have. When we weren’t getting where we thought we needed to be, it was pretty easy to call a strike,” he says. “And the teachers were ready to go.”

Sue Bauman, the chair of the 1976 MTI crisis committee who later served as mayor of Madison, says the district was often very persistent in rejecting and ignoring the needs of its teachers at the time, as well as years before the dispute.

With every request the union had, she says the school board always responded with one answer: “no.”

“To not say ‘no’ is conceding and they didn’t like to concede to us,” Matthews says. “They wanted things the way they were.”

Though the school board’s resistance to change was frustrating, Bauman says it was also used as a weapon against them, serving as motivation for more teachers to join in on the strike.

Behind the scenes of the intense picket lines, around-the-clock bargaining for the 1976 teachers’ contract was underway.

“I never got home for three weeks,” Matthews says. “We spent many days arguing and bargaining anywhere from 18 to 20 hours a day — sometimes all day and all night.”

MTI argued that the board’s proposed teacher salary was not representative of the increase in cost-of-living at the time. The teachers also picketed over other significant problems that made it difficult for them to perform their jobs.

Some of the teachers’ major requests from the school board included class planning time, improvement in teacher evaluation and strict class size limits, as well as significant improvement in wages and health insurance.

After both sides declared there was a tight deadlock in negotiation, the board requested an impartial fact-finder to help make a decision. What finally led to a conclusion to the strike and ultimately a win for the Madison teachers was an ultimatum.

“We had been in bargaining for 20 hours on that day and [the fact-finder] Anthony Sinicropi said, ‘nobody can leave this room until we settle this contract,’” Matthews recalls.

In a culmination of many hours of bargaining in a locked room between the teachers and the school board’s chief negotiator, MTI received what they vehemently declared as a win — among some of the changes to the contract was a nearly seven percent increase in base salary, improvement in health insurance benefits and guaranteed class planning time.

Though some were angry about the closing of Madison’s schools, Baumann says a majority of the community showed solidarity to the teachers and were ultimately supportive of the strike.

“I think people realized that teachers are really valuable and wanted to work with them,” she says. Baumann even recalls community members inviting picketers into their homes for warmth in the freezing, sub-zero weather.

And the support from the community and teachers on the picket lines made Mike Schwaegerl, chief bargainer for the 1976 union, feel assurance that the teachers would eventually come out with their victory.

“I was confident that we were going to win because we had all those people out there,” he says. “I really didn’t feel much pressure.”

Schwaegerl also points out similarities between the 1976 labor dispute in Madison to more recent teachers’ strikes throughout the nation. He references the nine-day Oklahoma teachers’ walk out in particular, which resulted in the teachers winning salary raises.

“The key there is that they never were able to collectively bargain before and they were always at the mercy of the legislators,” Schwaegerl says of the Oklahoma teachers.

For Matthews, the 1976 teachers’ strike and other strikes around the nation are a testament to the power and strength of unions, as well as of collective bargaining.

“This shows what people can accomplish if they get together and stick together,” he says. “Mutual support is extremely important. I hope people remember what they can accomplish if they stay militant.”

In 2011, the Wisconsin legislature passed the highly controversial bill Act 10, which severely limits collective bargaining rights for most public-sector employees.

This may signify the end to collective bargaining like that of the 1976 labor dispute, but Matthews says citizens should be empowered to make change for the years ahead.

“[This bill] is going to affect their work everyday from here forward and for the rest of their life until they’re put in the grave,” he says. “They’ve got to get together and get militant and demand their bargaining rights.”

Bauman says unions are necessary and must continue in advocating for the rights of others. She says, after all, that it’s their responsibility to take action.

“That’s what a good, strong union does,” she says. “You represent your members when they have an issue and when they feel like they’re being taken advantage of or wronged in some way, you fight on their behalf.”

Though the 1976 fight is over, Bauman, Matthews and Schwaegerl say they hope teachers in the state and across the nation will use this strike as an example to fight for their rights in the future.