By Ashley Luthern

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

A deputy falsifying jail logs. Officers stealing during a search warrant. An off-duty officer hitting a parked car after leaving a bar, then lying about it.

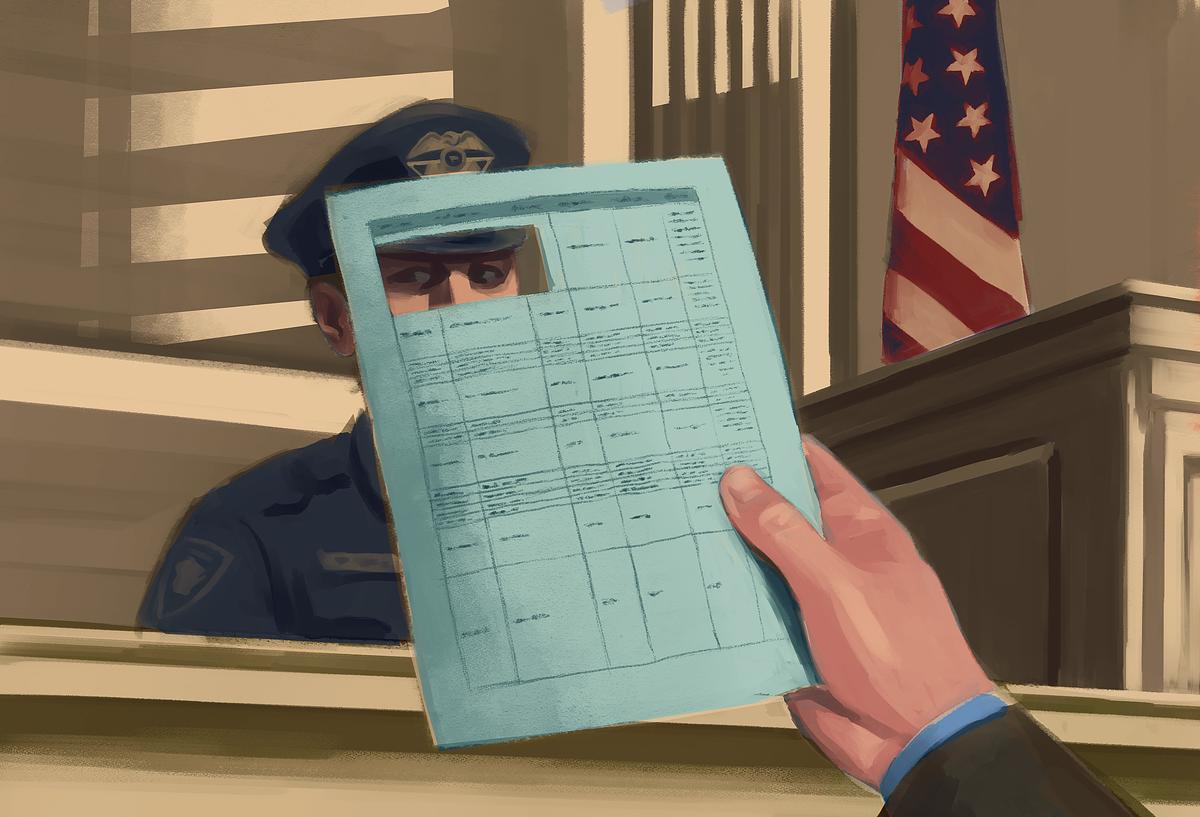

Imagine one of them arrested you.

Would you want to know about their past?

Under the law, you have a right to that information. How and when you get access to it depends on prosecutors, who file criminal charges and bring a case in court.

The Milwaukee County District Attorney’s Office has a system for tracking officers with credibility concerns, allegations of dishonesty or bias, and past criminal charges. But it is inconsistent and incomplete and relies, in part, on police agencies to report integrity violations, an investigation by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, TMJ4 News and Wisconsin Watch found.

After reporters provided Milwaukee County District Attorney Kent Lovern with their analysis and raised questions about specific cases, he removed seven officers from the database and acknowledged one officer should have been added to it years earlier.

The haphazard nature of these tracking systems fails officers and people defending themselves, said Rachel Moran, a professor at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis, who has extensively studied the issue nationwide.

“It does lead to wrongful convictions,” Moran said. “It leads to people spending time in jail and prison when they shouldn’t.”

Many criminal cases come down to whether jurors believe a defendant or a law enforcement officer.

The system of flagged officers — often known as a “Brady/Giglio list,” so named for two landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases — is meant to help prosecutors fulfill their legal duty to share evidence that could help prove someone’s innocence.

Wisconsin does not have statewide standards for how such Brady information should be gathered, maintained and disclosed. It falls to local district attorneys to decide how to gather and share information about officers’ credibility, leading to inconsistencies across the state’s 72 counties.

Lovern maintains his office is fulfilling its obligations. By compiling the spreadsheet, his office already is doing more than required, he said in an interview. Just because an officer is on the list does not mean he or she was necessarily convicted of a crime or had a sustained internal violation.

“The database is complete to the best of my knowledge and belief,” he said in a follow-up email in February, adding it always is subject to change with new information.

Some of those changes were prompted by this investigation, which found multiple inaccuracies in the Brady list released last fall. One officer was described as being involved in a custody death but he was not. Two were listed with the wrong agency. Another was listed for a criminal case that was expunged in 2002. At least five officers on the list were deceased.

After reporters raised questions, a West Allis officer who resigned after admitting he had sex with a woman while on duty at a school was removed from the list because, Lovern said, he did not lie about what he did. That officer was hired at another agency in the county.

The inconsistencies in Milwaukee County’s Brady list have frustrated defense attorneys and advocates for police officers — one union leader called it the “wild, wild west” — and are another example of a nationwide problem for legal experts like Moran.

“It’s just an ongoing travesty of constitutional violations,” she said. “It is a huge national problem that should be a national scandal.”

Who is on the Milwaukee County Brady list and why?

The district attorney’s office started tracking officers with documented credibility concerns more than 25 years ago.

The full list has not been made public — until now.

The move came after years of pressure from defense attorneys, media outlets and a lawsuit threat. The decision to release the list was harshly criticized by Alexander Ayala, president of the Milwaukee Police Association, the union representing rank-and-file officers in the city.

“It’s only going to be detrimental to police officers or even ex-police officers because they’re trying to move on,” he said.

The district attorney’s office first released the list to media outlets last September in response to public records requests. At the time, Assistant District Attorney Sara Sadowski wrote, in part: “This office makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of the record.”

She also said that some criminal cases may have “resulted in an acquittal, that charges were dismissed, or that charges were amended to non-criminal offenses.”

That list, dated Sept. 20, contained 218 entries involving 192 officers and included a wide range of conduct, from a recruit who cheated on a test to officers sentenced to federal prison for civil rights violations.

The Journal Sentinel, TMJ4 and Wisconsin Watch spent five months tracking down information about the officers through court documents, internal police records and past media coverage.

Milwaukee police officers made up the largest share of officers on the list, but nearly every suburban police agency in the county was represented, as well as the Wisconsin Department of Justice and the Wisconsin Department of Corrections.

At least a dozen officers kept their jobs after being placed on the Brady list, then landed on the list again.

One of them was Milwaukee County sheriff’s deputy Joel Streicher.

Back in 2007, Streicher and five other deputies searched a drug suspect’s house without a warrant, according to a previous Journal Sentinel article. It wasn’t until 2019 that Streicher was added to the Brady list when he was caught up in a prostitution sting and pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct.

A year later, Streicher was on duty when he ran a red light near the courthouse and killed community advocate Ceasar Stinson. He resigned and pleaded guilty to homicide by negligent operation of a vehicle. Streicher declined to comment when reached by a reporter last month.

Criminal cases like Streicher’s represent three-quarters of the entries on the Brady list. The other quarter are tied to internal investigations.

The news organizations also found:

- Of the 218 entries on the list, about 47% related to a direct integrity or misconduct issue, such as officers lying on or off duty. The allegations vary: One officer pleaded guilty to taking bribes for filling out bogus vehicle titles and was fired. Another former officer was charged with pressuring the victim in her son’s domestic violence case to recant. A lieutenant was demoted after wrongly claiming $1,800 in overtime.

- About 14% related to domestic or intimate partner violence, and nearly 10% related to sex crimes, such as sexual assault or possessing child pornography.

- Another 14% involved alcohol-related offenses, most often drunken driving. At least six cases involved officers, most off duty, who were found to be driving drunk and had a gun with them.

Nearly 7% involved allegations of excessive force. One of the officers listed in the database for such a violation was former Milwaukee officer Vincent Woller, who was added in 2009 after receiving a 60-day suspension for kicking a handcuffed suspect in the head, according to previous Journal Sentinel reporting.

Woller remained on the force until last year. He recently told a TMJ4 reporter he had testified “hundreds” of times in the past 15 years and never knew he was on the Brady list.

When asked to respond, Lovern, the district attorney, removed Woller from the list, saying Woller’s internal violation was not related to untruthfulness.

Lovern, who served for 16 years as the top deputy to his predecessor, John Chisholm, said he reviews any potential Brady material brought to his attention from the defense bar.

In those cases, he said, he often has concluded that while officers’ conduct may show “poor judgment,” it did not relate to credibility or untruthfulness.

Others have strongly disagreed with those decisions.

Three years ago, the State Public Defender’s Office asked for the full Milwaukee County Brady list, only to receive a partial list of about 150 names of officers charged or convicted of crimes.

Public defenders then shared police disciplinary records they had obtained while investigating and trying past cases, said Angel Johnson, regional attorney manager for the State Public Defender’s Office in Milwaukee.

Johnson had expected those officers would be added to the list.

“They were not,” she said.

How some police officers can be on the Brady list and keep their jobs

The Brady list is not a blacklist.

Eighteen officers are still employed by the Milwaukee Police Department, while five others are members of the Milwaukee County Sheriff’s Office, according to representatives for those agencies.

In some cases, an officer’s past integrity violation or criminal conviction, such as drunken driving, may not necessarily prohibit the officer from testifying. That means they can still be useful as police officers, officials say.

“For us, it’s not about being placed on the list, it is how they will be used by the district attorney’s office,” Milwaukee Police Chief Jeffrey Norman said in an interview.

Norman said he does consider an officer’s ability to testify when weighing internal discipline.

Milwaukee County Sheriff Denita Ball said she does not, instead concluding the internal investigation and deciding discipline before forwarding any information to the District Attorney’s Office.

“Somebody can just make a mistake,” Ball said. “If that’s the case, then their employment is retained.”

Norman stressed he takes integrity violations seriously and makes his disciplinary decisions after reviewing internal investigations, officers’ work histories, comparable discipline in similar cases and input from his command staff.

Depending on those factors, officers can keep their jobs despite an integrity violation.

Officers Benjaman Bender and Juwon Madlock were working at District 7 on the city’s north side in 2021 when a man reported that he had just been shot at in his vehicle a few blocks away, according to records from the department and the Fire and Police Commission.

The man handed Bender his ID. The officers did not write down his name, inspect his damaged car parked outside, interview witnesses, or ask him any other investigatory questions, even after the man took a call from someone involved in the shooting.

Instead, Bender instructed the man to return to the crime scene by himself and told him a squad would meet him there.

“So it’s cool for people to just go shoot at people now?” the man replied.

“Just go over there,” Madlock said, as he returned the man’s ID.

Bender later told a sergeant the man had been uncooperative and that he did not see the man’s ID. Madlock told another sergeant the man had walked out on his own. Video from the lobby contradicted their accounts.

Internal affairs found both officers failed to thoroughly investigate and had not been “forthright and candid” with supervisors.

Norman suspended each officer for 10 days. They remain employed — and on the Brady list.

The department did not authorize the officers to speak with a reporter for this story.

In rare cases, the district attorney’s office will decide that an officer can never be called as a witness. Only two or three officers in the county have received that designation in the last 18 years, and none are still employed as officers, Lovern said.

Reporters were unable to track the current employment of every officer on the Brady list because the Wisconsin Department of Justice has refused to release a statewide list of all certified law enforcement officers, a decision that is being challenged in court.

The state has released a separate database of officers who were fired, resigned instead of being fired or quit while an internal investigation was pending.

A comparison to that database showed at least four officers on the Sept. 20 Brady list were working at different law enforcement agencies in the state.

Credibility matters whether you’re an officer or a citizen accused of a crime

There’s no guarantee an officer’s past will come up in court.

A defense attorney has to decide whether to raise it. And if they do, a judge has to decide if a jury should hear about it.

But for any of that to happen, prosecutors must collect and disclose the information in the first place.

“We don’t monitor the Brady list,” said Milwaukee County Chief Judge Carl Ashley, who added that he has never encountered a Brady issue during his 25 years on the bench.

“We get involved once the matter is brought to our attention,” he said.

Some prosecutors across the country come up with different systems to learn of potential Brady material. In Chicago, prosecutors started asking police officers a series of questions, such as if they had been disciplined before or found to be untruthful in court, before using them as witnesses.

In Milwaukee County, the district attorney’s office relies on police agencies to self-report internal violations. Lovern defended the practice, saying the local agencies are “very direct with us.”

But that approach leaves gaps.

Out of 23 law enforcement agencies in Milwaukee County, only seven provided a written policy detailing how they handle Brady material in response to a records request sent in November.

The Milwaukee Police Department and eight other agencies in the county do not have a written policy, and the other agencies did not respond or the request remains pending.

Regardless, prosecutors have a constitutional requirement to find and disclose potential Brady material, whether the records are located in their office or at another agency, said Moran, the law professor.

“Prosecutors still have the ultimate obligation for setting up information-sharing systems,” she said.

Sometimes, officers slip through the cracks.

Before Frank Williams landed on the Brady list, the Milwaukee police officer had a history of misconduct allegations dating back to 2017. He had been investigated for excessive force, improperly turning off his body camera and interfering with investigations into his relatives, according to internal affairs records.

His harshest punishment, a 30-day suspension in 2021, was for an integrity violation after he falsely reported he had stayed at home on a sick day when he instead played in a basketball tournament.

But Williams was not added to the Brady list until last year, when prosecutors charged him with child abuse. He later pleaded guilty to lesser charges of disorderly conduct and was forced to resign. Attempts to reach Williams and his attorney by phone and email were not successful.

When asked why Williams was not placed on the list earlier, Lovern said the Milwaukee Police Department did refer Williams for Brady list consideration in May 2021 after the integrity violation, and Williams should have been added then.

Lovern said he should have forwarded Williams’ information to a staff member to include him in the database. He found no record that he actually did.

As a result, Lovern’s office is now contacting anybody who was convicted in cases where Williams was a named witness in the three-year period he should have been in the database.

Officials with the State Public Defender’s Office said they appreciated Lovern’s decision, but said the case shows what can happen when a Brady list is incomplete.

“The ability to question those witnesses against our client and their credibility is fundamental,” said Bridget Krause, trial division director for the State Public Defender’s Office.

If the information is not disclosed, it can have devastating consequences.

“You can’t go back and unring some bells,” Krause said. “Somebody who served 18 months in prison and now you’re finding out this could have impacted their case, they can’t not serve that time.”

Criminal defense attorneys who regularly practice in Milwaukee County say they rarely receive disclosures about officers’ credibility.

One said he had been practicing for nearly 20 years and had never received one. Another said the district attorney’s office practices amounted to a policy of “don’t ask, don’t tell.”

Johnson, a manager for the state public defender’s office in Milwaukee, has practiced in the county for 10 years and tried numerous criminal cases.

She said she’s received two Brady disclosures related to officers’ credibility.

Both came this year.

About this project

This is the first installment in “Duty to Disclose,” an ongoing investigation by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, TMJ4 and Wisconsin Watch into the Milwaukee County district attorney’s “Brady list,” a list of law enforcement officers deemed by the Milwaukee County District Attorney’s Office to have credibility issues. The office publicly released the list in full for the first time in late 2024 after pressure from the news organizations.

Journal Sentinel investigative reporter Ashley Luthern, TMJ4 investigative reporter Ben Jordan and Wisconsin Watch investigative reporter Mario Koran spent five months verifying information of the nearly 200 officers on the list, discovering that it is frequently incomplete and inconsistent.

Readers with questions or tips about the Brady list can contact the Journal Sentinel’s investigative team at [email protected].