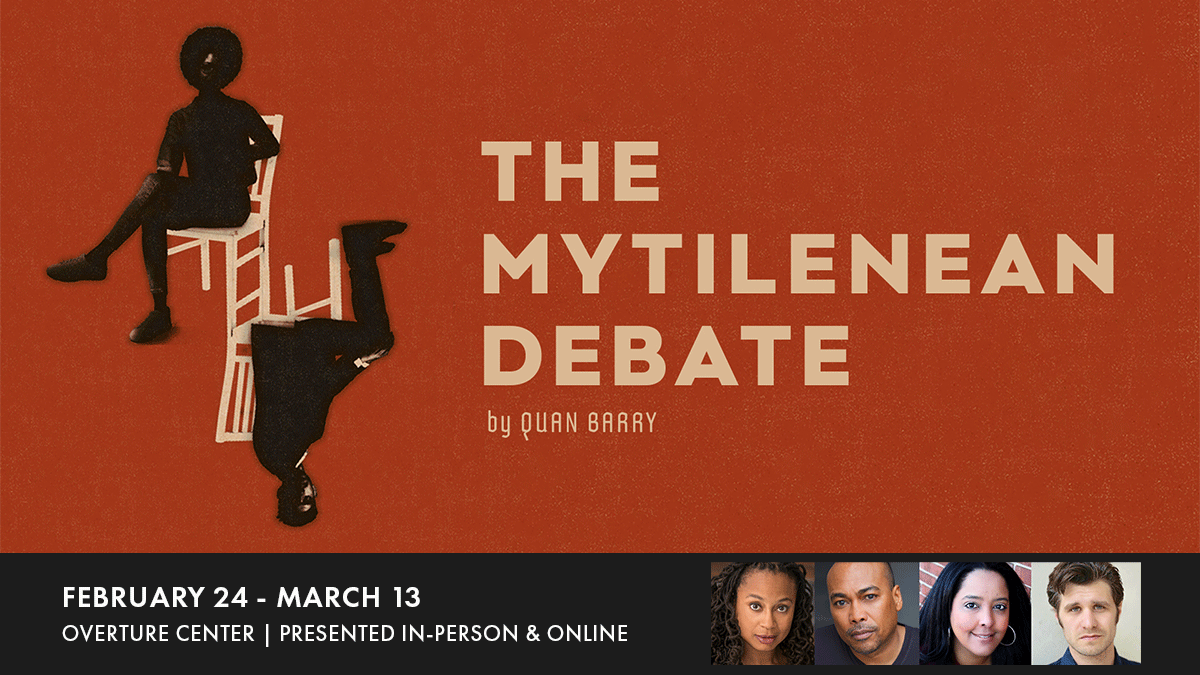

“Your whole life you tell yourself one thing or another until you start to believe it, until it’s a simple fact, a part of your biography,” muses one of the characters in Quan Barry’s The Mytilenean Debate, receiving its world premiere production courtesy of Forward Theater from February 24 to March 13.

But what if the things you’ve been telling yourself are wrong and misinformed? Comfortable but closed? Worse, what if you’re not even asking yourself such questions? In staying blindly true to the path of what you’ve always assumed is right, are you failing to see how you might be going wrong?

Writing in a more confident age, Emerson believed that “foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Living in a darker and more fearful time, we’re more apt to dismiss those changing their minds as flipfloppers.

Undeterred, Barry takes the title of her play from one of the most famous flip-flops in world history.

Early in the 5th-century BCE Peloponnesian War, Athens decided to teach the recently vanquished city-state of Mytilene a lesson by killing all Mytilenean men and selling all Mytilenean women and children into slavery; a galley was dispatched across the Aegean to deliver the news and execute the order.

The next day, the Athenians had second thoughts; following a tumultuous debate, they changed their mind. A second, double-manned galley rowed furiously to overtake the first. It arrived in Mytilene just in time to prevent a mass execution.

Caught in a Trap

Like those long-ago Athenians, all four of Barry’s characters – three Black and one white – are debating with themselves and each other regarding the choices they’ve made and how it’s shaped who they’ve become.

Latimer is a renowned heart surgeon whose escape from a hard-scrabble, racially inflected Mississippi childhood risks transforming his ensuing life into a carefully choreographed performance, in which he keeps it together with studied cool lest he falls apart at memories of things past.

Latimer’s younger partner Nina, a hot-shot television producer who finds herself unexpectedly pregnant, is wrestling with whether to become a mother in a country that’s increasingly intolerant of women choosing differently.

As Nina considers whether to abort, Latimer’s daughter Mary is desperately trying to conceive – even as Charles, her white husband and a devoted jazz musician, wonders whether he’ll ever be ready to become a father.

None of these decisions are made easier by expectations – often imposed – regarding who we should be.

“People look at us and try to categorize, try to figure us out,” Latimer points out to Nina. “It makes their world nice and tidy.”

“People think jazz is about me rebelling against some Norman Rockwell suburban crap,” Charles complains to Latimer. “That’s the only way people can explain me.”

The Mytilenean Debate explores how such expectations define us and restrict our choices, making it hard to think anew on issues including parenting and adoption. Gender. The intersection of race and class. What it means to grow old, and how hard it is to be young. How to remake the past, even though Faulkner rightly recognized it’s not ever even past.

Transforming Histories

As with her four poetry collections and first two novels – I’m writing these words just weeks before publication of her third – Barry never suggests that in choosing again or differently we can ignore the choices we’ve made or histories we’ve inherited.

“There are places on the human body that will not heal/due to their constantly being in motion,/their flexing and such, the skin unable/to hold a scab,” Barry writes at the beginning of “meditations,” a brilliant poem exploring the truths we hold and how they evolve.

But even if we can’t ever fully transcend the past, might we not expand how it plays in the future, imagining new sounds even as we replay old songs?

At the end of this same poem, Barry describes Mongolian singers “who can sing two notes at the same time.” In another poem in the same collection, Barry offers a variation on this theme by invoking “polyphony, the story after the story.”

In her poems and novels, Barry continually revisits the past, refusing to flinch from the nightmare of history and recognizing, as she says in her poem “Thanksgiving,” how its horrors necessarily live on within each of us.

But like each of her characters in The Mytilenean Debate, Barry also resists the idea that we must be forever stuck in where and what we once were.

In an interview after the publication of her novel She Weeps Each Time You’re Born – a wrenching, gorgeous love song to her native Vietnam – Barry referenced how Viet Nam has remade itself. “I’m most interested,” she told NPR’s Scott Simon, “in the idea of possibility, and how so much can change.”

The Mytilenean Debate drives home what all of Barry’s work makes clear: change is hard and inevitably leaves scars. “Any decision you make, you’re going to have regrets,” reflected Jennifer Uphoff Gray, referencing the “big, life-changing decisions” confronting the characters in Barry’s play. “The path you didn’t take is always going to be out there, reminding you that you didn’t take it.”

But failing to choose or change – for fear that being inconsistent or different may alter the way you see yourself and the world – is itself a choice, to hunker down with personal and political certainties rather than exposing ourselves by exploring new terrain.

“Ideological inconsistency is, for me, practically an article of faith” Zadie Smith wrote more than a decade ago, in an essay collection appropriately entitled Changing My Mind. Poised at significant crossroads in their lives, Barry’s characters are each wrestling with what such inconsistency might mean, for themselves and those they love.

Are the characters in The Mytilenean Debate choosing wisely and well? Watching Barry’s play, I wager you’ll be debating such questions with yourself, in conversations that will carry on long after you leave the Playhouse. That’s how great theater works. That’s what this play does.

For more information and tickets, The Mytilenean Debate, visit https://forwardtheater.com/.

– Mike Fischer