Trauma disrupts. It fragments, perforates and scrambles.

That’s one of the many messages of Quanda Johnson’s exhibit “Trauerspiel: Subject Into Nonbeing,” an autoethnographic meditation on anti-Black violence and its consequential trauma that is now on display at the Chazen Museum of Art in downtown Madison.

The exhibit uses interdisciplinary creative making to explore three arenas of white-dominated violence against the Black body/psyche: the violence of ridicule, the violence of the mob/vigilante, and the hegemonically instigated violence that seeps into some “safe Black spaces.”

(Photo by David Dahmer)

Johnson is a University of Wisconsin-Madison dissertator who works interdisciplinarity through the platforms of visual culture and performance. The impetus for this exhibit first came when Johnson was finishing the third of three master’s degrees at New York University (NYU) while taking a class called “Racial Literacy in the Archive” and reading Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson. That’s where she came across the name – Anthony Crawford, a name she recognized at the time but wasn’t quite sure how or why.

“The reaction I had when I read his name was visceral. So I went back and looked through our own family archives, which are funeral programs. Most Black folks in the United States collect funeral programs of their recently deceased and the long deceased,” Johnson remembers. “So I start leafing through, and I see something from Jesse Lee Smith, and this is my grandfather’s cousin. And I start reading the first paragraph which says that our family came to Philadelphia from Abbeville, South Carolina, as a result of the lynching of Anthony Crawford. This is how I came to be born in Philadelphia.”

With some further research, Johnson found out that Crawford, the wealthiest man in Abbeville, South Carolina, was lynched in 1916 by a crowd of hundreds of “blood-thirsty white people.”

“He was lynched for the crime of not knowing his place,” Johnson says. “So that just put me on this trajectory of interrogating violence, and how violence is perpetrated on us. And also keep in mind at the same time that I’m making this discovery that this is 2015. So we have that incredible massacre that happens in South Carolina where the nine [Black] parishioners are murdered by Dylann Roof. This is the time of the killing of Michael Brown. We have just a litany of unarmed Black men and women being murdered. And so this violence is very present, in my mind and in my psyche.”

Anthony Crawford’s life is explored in The Ballad of Anthony Crawford: remix (2019-2022), one of the three segments of the exhibit, that examines the power of the white mob to destroy not only one human life, that of Johnson’s ancestor Anthony Crawford, but to alter an entire community’s destiny. The patriarch of a large, multi-generational family and the owner of 427 acres of land, Crawford’s sizeable wealth and land were seized after his murder.

Meanwhile, “In Search of Negroland: beauty suspended” is another section of Johnson’s exhibit, and asks, as author and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois once did, “What is it about whiteness that it is so desired?”

“’In Search of Negroland: beauty suspended’ deals with violence of ridicule. And when you look at the panels there, you see how we would envision our bodies within the space and then three kinds of tropic indicators of Blackness — you’ve got the hair at the top there, you have the shapes of the noses at the next one along with the thickness of the lips. And then, of course, the roundness of the bottoms,” Johnson says.

“The hegemony that the white-dominated culture laughs at and ridicules but at the same time appropriates,” she adds. “They desire that which they consider grotesque.”

The third segment, the titular “Trauerspiel: subject into non…being,” reflects horror and hope as one family struggles with its legacy and fortitude. It is a look into Johnson’s own family – father, mother, brother and Johnson herself.

“The poem that accompanies ‘Trauerspiel: subject into non being … the sum of it all’ is the summation, working from the outside in, from the ridicule to the violence of the body, the psychological violence, to how this impacts some homes,” she says. “And I’m very careful to say some, because not all Black homes are riddled with violence. That’s a common mythology.

“So while I interrogate my own situation, because this is all autoethnography as well as being practice/performances research, I want to make sure that the public knows that this is a very singular and unique response to hegemonic violence, and is not to be taken as something that’s across the board,” Johnson adds.

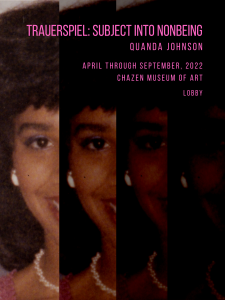

The photo in the exhibit is of Johnson’s four family members in the late ‘80s. “My father was an obsessively violent man, I won’t go into the details. He died of alcohol poisoning. In fact, it’s one of the rare times where you look at a person’s death certificate and under cause of death, it actually says ‘chronic alcoholism,'” Johnson says. “My mom was into fashion and was beautiful, but because of what she was dealing with, she died very young. She died of systemic lupus. My brother has severe autism and struggled with autism. And then there’s me. So you look at that image of the four of us seated there. And we’re each dealing with our own personal demons in that image. But you don’t know it.

“I think it was probably the last photo that we took as a family. So it’s like a shiny red apple. And you cut it open and it’s full of worms,” Johnson adds. “On the appearance, we looked like, you know, we just stepped out of Ebony Magazine, right? But inside there is all of this contending with trauma. And what do you do with that trauma if you don’t have the tools to process it?”

Johnson says that the response to “Trauerspiel: Subject into Nonbeing” has been very positive so far. Does she worry that many people who might really benefit from seeing an exhibit on anti-Black violence and its consequential trauma, aren’t seeing it because of the uncomfortable content?

“Sometimes you feel that you’re preaching to the choir. I get that,” she says. “But you never know because we don’t know everybody’s narrative. And I’ve had people — Asian, white, Black, of course — tell me that ‘In some way. This story is my story. This is what I got from this …and that’s my experience, too.’ And they don’t necessarily have to be Black. The trauma and the weighing of it, and the measuring, and the navigating … And how do you negotiate within all of those things?“

For white people, this long history of anti-Black violence and the trauma laid out in public may make them feel uncomfortable. But, Johnson says, it’s important to learn about it.

“If we don’t learn about this and acknowledge this, then nothing gets solved,” Johnson says. “How do you think that the problems that this country faces due to our original sin will ever be addressed? How are we ever going to learn how to see the other as ourselves if we refuse to talk about it, if we refuse to teach it, if we exile it out of history? It already has been. I didn’t learn half of the stuff that I was supposed to learn in high school history.

“For so many years, we have basically been putting a bandage over a cancer …. and then we are surprised when things go wrong,” she adds.

“Trauerspiel: Subject into Nonbeing,” an autoethnographic meditation on anti-Black violence and its consequential trauma, is now on display at the Chazen Museum of Art, 800 University Ave.