Inside the memory care unit at Parkview Gardens, a senior living community in Racine, Marten held her father’s hand. He was asleep, but Marten sensed he knew she was there. Marten told him she loved him and sang “My Funny Valentine,” a song Shore taught her when she was a child.

Those would be her last 30 minutes with her father, who died the next day — five days after testing positive for COVID-19.

Marten, a Montessori school teacher from Wauwatosa, knew her father didn’t have many years left, even before he caught the coronavirus. Shore had lived with Alzheimer’s disease for about a decade when Marten enrolled him in hospice care in March — one day before Department of Health Services Secretary-Designee Andrea Palm issued Wisconsin’s “Safer at Home” order at the direction of Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat.

But Marten wasn’t prepared for Shore’s life to end so suddenly at age 75.

Palm’s order shuttered a variety of businesses and public spaces, after the state advised nursing homes to bar most visits to slow the spread of coronavirus. But when the Wisconsin Supreme Court lifted the order in May, Marten worried the virus would creep into Parkview Gardens, and her vulnerable father wouldn’t have a chance. Marten said the community asked families to voluntarily avoid visits to protect residents, and she voiced support to administrators.

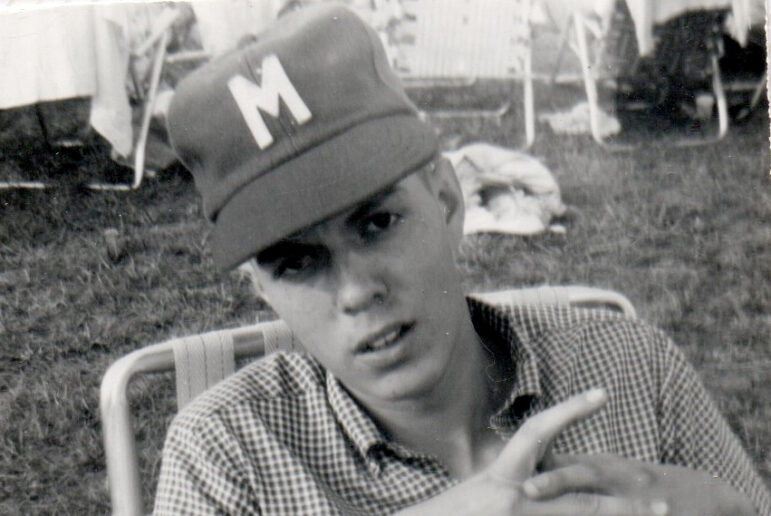

But by July 11, Shore was gone. The former minor league baseball pitcher, journalist, author, software engineer and entrepreneur is among more than 1,850 Wisconsinites and 225,000 Americans — all with their own stories — who have died after being diagnosed with COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

“The thing that still bothers me is that my dad is one of those numbers,” Marten said. “I just hate that he and so many other people’s parents have been added to such an anonymous list.”

More than seven months into the pandemic, public health experts have taken huge strides in understanding how to limit the spread of COVID-19. Much remains simple: Wear a mask. Keep a distance. Wash your hands. Avoid large gatherings — especially indoors.

Yet many Wisconsinites are ignoring this guidance, causing hospitalizations and deaths to surge, transforming the state into one of the country’s biggest virus hotspots.

A key ingredient missing from the pandemic response, public health experts say: consistent messaging from government leaders. The looming presidential election has transformed the pandemic into a national political issue. President Donald Trump and Republican allies often downplay the severity of COVID-19 — and scoff at the demonstrated effectiveness of tools like masks and distancing, while Democrats amplify the voices of public health experts and push for more restrictions to slow the virus.

Perhaps nowhere is that message more muddled than the presidential swing state of Wisconsin. The Republican-controlled Legislature successfully sued to end Safer at Home, and it pushed back against Evers’ subsequent orders — a mask-wearing mandate and capacity limits on indoor gatherings. Republican lawmakers claim Evers has overstepped his authority, but they have offered no plans of their own to slow the virus.

Meanwhile, as Evers and his health officials urge residents to avoid gatherings and wear masks when in public, some Wisconsin Republicans continue to flout the mask mandate at meetings and rallies — some of them indoors, where the virus is more likely to spread. The offices of Assembly Speaker Robin Vos and Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald — the top two GOP leaders — have both been beset by COVID-19 outbreaks among their staff, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

“Unfortunately we are having a pandemic in an election year — in a swing state where the governor and the (Legislature) are not from the same political aisle,” said Dominique Brossard, a professor and chair of the Department of Life Sciences Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “You couldn’t be more complicated than the state government of Wisconsin right now.”

The dueling messages — and whiplash from legal rulings on Evers’ pandemic efforts — have paralyzed state government during a crisis that calls for collective action.

Wisconsinites are living and dying with the consequences.

‘It’s all about messaging’

Wisconsin ranked third among states in coronavirus infections per capita as of Oct. 27, according to tracking by The New York Times. Wisconsin trailed only Texas, Illinois and California in total infections over the past week, despite having a fraction of those states’ populations.

The prolonged surge is rendering contact tracers unable to warn everyone who may have been exposed to the virus, and it is overwhelming hospitals with COVID-19 patients — enough to prompt Evers to open a field hospital on the grounds of Wisconsin State Fair Park in West Allis.

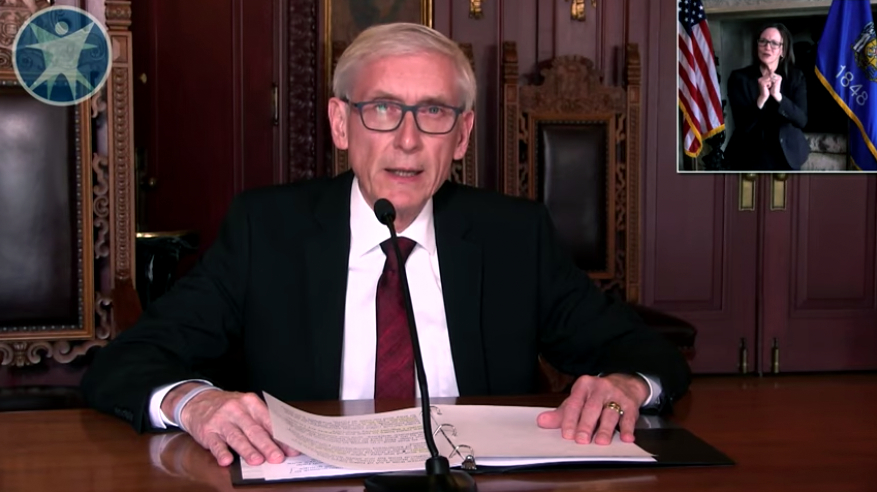

“Our nurses, health care staff and physicians are working long, frankly, emotionally exhausting hours on the frontlines caring for COVID patients and putting their own health and safety on the line,” Evers said at an Oct. 22 press briefing. “Make no mistake about this: This is an urgent crisis.”

(Wisconsin Department of Health Services via YouTube)

A positive data point amid the darkness: Some 5.6 million Wisconsinites have yet to test positive for COVID-19, and most can avoid the disease by taking simple precautions.

“You can stop COVID spread with enough (protective gear) and enough precautions and enough buy-in from everybody,” said Ajay Sethi, a professor at the UW-Madison and director of its Master of Public Health program.

“It’s all about messaging.”

The fundamentals for responding to a virus with no vaccine or cure have changed little over a century. Wisconsin, in fact, was the only state in 1918 to confront the misnamed “Spanish flu” with uniform shutdown measures, which historians credit with limiting casualties from a virus that killed an estimated 675,000 Americans.

Milwaukee was among the nation’s top cities in minimizing flu casualties, thanks in part to City Health Commissioner George Ruhland. He built a multi-partisan political coalition that gained broad support for mask wearing and other precautions, according to Steven Burg, a professor of history at Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania, who authored a history of Wisconsin’s response to the 1918 pandemic.

Successful public health interventions often pair mandates with messaging campaigns, Brossard said. They include a widely successful U.S. campaign to encourage people to quit using cancer-causing tobacco products. A national quitline complemented bans on tobacco sales to younger people and local ordinances banning smoking indoors. The result: a 67% decline in U.S. cigarette smoking rates since 1965.

Sethi said UW-Madison exemplifies a local model of success for curbing COVID-19. Following a massive outbreak in September as students returned for the fall semester, administrators enacted sweeping restrictions, including temporarily moving classes online, ordering students in two dormitories to quarantine and frequently testing students for the virus.

Infections have since plummeted, a trend playing out on other campuses nationwide. Experts say stricter punishments for rule-breakers may be prompting more students to take precautions, but luck may also play a role, along with clear communication.

“Here at the UW-Madison campus there is probably a lot more cooperation compared to when you get to a larger scale — where you have more voices, more diverse opinions and many more channels of communication,” Sethi said.

“I think it’s a microcosm of what we can achieve at a state level if we didn’t have those barriers — and at a national level.”

Paralyzing a pandemic response

Evers has sought to pursue similar strategies statewide. Republican lawmakers have fought nearly every step, beginning with the Legislature’s lawsuit to overturn Safer at Home.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court’s May 13 ruling immediately lifted the order, leaving some local governments to enforce their own regulations amid legal confusion. The justices ruled that Palm overstepped her authority by shutting down businesses and public spaces, and they expected the administration to propose a new plan through a legislative rulemaking process.

But Republicans rejected the new plan days later, with Sen. Steve Nass, R-Whitewater, accusing Palm of “once again trying to improperly take control of the daily lives of every Wisconsin citizen.”

(Courtesy of Harper Marten)

In late July, as Wisconsin’s recorded COVID-19 deaths surpassed 900, Evers ordered a mask mandate for most public buildings in the state, following 32 other states with similar requirements. GOP lawmakers immediately criticized the move. Fitzgerald, R-Juneau, said his colleagues stood “ready to convene” to overturn it.

The Legislature did not meet, but it did back a conservative legal group’s thus-far unsuccessful challenge of the order, arguing Evers lacked the power to issue a new public health emergency and enact a mask mandate. During the political tussles in Madison, a host of local law enforcement agencies announced they would not enforce the mandate.

As total COVID-19 deaths neared 1,400 earlier this month, Evers instructed Palm to order 25% indoor capacity limits on stores, restaurants and bars, which have become a national focal point of outbreaks. The powerful Tavern League of Wisconsin quickly sued with other businesses, triggering court rulings that blocked, reinstated and again blocked the order in a dizzying 10-day span.

Lawmakers ‘sit back’

The Legislature has not passed a bill since a COVID-19 relief package on April 15, making it the least-active full-time legislative body in the country, according to a WisPolitics.com analysis.

Neither Fitzgerald nor Vos, R-Rochester, responded to emailed questions sent to their spokespeople for this story.

Their colleagues are questioning the need to enact a plan to control the virus.

“We can’t wave a wand and make it go away,” state Rep. Joe Sanfelippo, R-New Berlin, said in a WisconsinEye interview on Oct. 20, adding: “There isn’t a lot that we can do as politicians, but we need to sit back, let the medical community figure this out, give them the resources they need to do it and let them do it.”

Sanfelippo, chairman of the Assembly committee on health, was among a group of GOP lawmakers who attended an indoor mass gathering — many not wearing masks — hosted by an anti-abortion group, according to the Wisconsin State Journal.

Other Wisconsin Republicans have contradicted medical research by suggesting that masks don’t slow the virus, and some have questioned patient loads inside hospitals, even as weary doctors and nurses describe dire conditions.

Such statements threaten to counteract those urging people to take precautions, including scattered messages from some Republicans.

The inconsistent messaging around the pandemic “increased the confusion about what was the best thing to do,” Brossard said.

What is clear: Many Wisconsinites are not staying home. Mobility within the state returned to pre-pandemic levels just weeks after the Supreme Court ruling, where it has hovered since, according to an Oct. 11 White House Coronavirus Task Force report.

Failure to follow masking and distancing guidelines will cause “preventable deaths,” the report said, adding: “State leaders should work intensely with communities to ensure a clear and shared message.”

Lawmakers are countering Evers’ message even as Republican governors in some other states take action to slow the virus.

Infection spikes this summer prompted the Republican governors of Texas and Florida to order bars closed after showing reluctance to do so earlier in the pandemic. Arizona saw COVID-19 infections plummet 75% in the weeks after Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican, lifted his ban on enforcement of local mask mandates in June, according to a U.S. Centers for Disease Control report that said restrictions on businesses may have also helped.

The governors “realized there were people dying above what they would want,” said Dr. Cyrus Shahpar, director of the Prevent Epidemics team at Resolve to Save Lives, an initiative of the global public health organization Vital Strategies. “I think Wisconsin is headed in that direction.”

A family fights COVID, then grieves

Wisconsin’s failure to control the virus is leaving more families to grieve lives lost, including Duane Bark’s.

Bark — the popular superintendent for Markesan District Schools, mentor and former football coach — was admitted to the hospital on July 23, his 61st birthday. He had COVID-19 but no other underlying conditions, according to his family. He was hooked up to a ventilator by August and placed in a medically induced coma.

The sight was surreal, recalled Bradley Bark, Duane’s oldest son. “This is our hero. This is our mentor. This is our coach. This is our dad — that is laying in there with a tube down his throat just to help him breathe.”

Duane fought hard for three months, his family said, but by Oct. 7, his organs were failing, and his family gathered around his hospital bed one last time.

Bradley read Bible verses of comfort. When he punctuated The Lord’s Prayer with an “Amen,” Duane opened his eyes for the first time in over a week, Bradley said.

“(There were) tears coming out of his eyes,” Bradley said, “and he flatlined at that point.”

“It was extremely sad and comforting, too. We know where he’s at right now. That’s the part that gives me some hope … We were by his side,” he said.

Brian Bark, Duane’s middle child, suspects a friend brought the virus into the family’s east central Wisconsin home during a maskless visit. The virus also sent Duane’s wife, daughter and mother-in-law to the hospital. Unlike Duane, they were released.

The family friend made it clear that he was going to bars after the court lifted Safer at Home, Brian said.

“Very poor decisions on that. Not wearing masks. Being around people nonstop,” he added. “I have a lot of anger towards that person.”

Similarities in Michigan fight

Wisconsin isn’t the only state in which a Republican-controlled Legislature has targeted a Democratic’s governor’s pandemic response. A similar fight is playing out in Michigan, where the state Supreme Court this month declared unconstitutional a law Gov. Gretchen Whitmer had used to repeatedly extend her emergency powers during the pandemic to issue mask requirements and crowd restrictions.

That ruling came days before the FBI announced it had foiled an alleged plot to kidnap Whitmer. The suspects were reportedly angered by her executive orders.

An estimated 1,500 protesters, most of them not wearing face masks and many carrying American flags, gathered at the Wisconsin State Capitol on April 24, 2020 for a 90-minute demonstration demanding an end to the shutdown of public spaces and business in Wisconsin aimed at curbing the coronavirus pandemic. Six months later, Wisconsin has become a national COVID-19 hotspot, with deaths and hospitalizations mounting. Public health experts say mixed messaging from state leaders has harmed efforts to encourage Wisconsinites to wear masks and keep a distance to keep the virus from spreading. (Will Cioci / Wisconsin Watch)

COVID-19 infections in Michigan and other states have surged in recent days. Still, Michigan averaged less than one-third of Wisconsin’s cases per capita over the past seven days, according to data compiled by The New York Times. Michigan was also reporting fewer hospitalizations than its neighbor — even though Michigan has 70% more residents. Some of Michigan’s biggest hotspots sit along its Upper Peninsula border with Wisconsin.

Peter Jacobson, a University of Michigan professor emeritus of public health law and policy, called Wisconsin’s caseload a “nightmare scenario” and flagged key distinctions in each state’s response to the pandemic. Most notably: Whitmer has continued to wield pandemic powers that Evers has proved unable to grasp.

Some of her administration’s health mandates remained in effect, even after the Supreme Court setback. The administration reinstated some restrictions through other maneuvers before the ruling took effect; The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services issued those new regulations rather than Whitmer herself.

Alta Charo, professor of law and bioethics at UW-Madison, said questions surrounding a governor’s emergency powers leave room for reasonable disagreement.

“Emergency powers always pose a bit of a conundrum for a democratic society, because essentially, they are invoked to remove the kinds of democratic protections that we have in place to guard against overly authoritarian, overly individualistic policies,” she said.

But she said Wisconsin Republicans appear to be arguing in bad faith, seeking cover for “a tremendously brutal struggle for power.”

During a 2018 lame duck session, the Legislature shrank some of Evers’s powers even before he took office.

“Unless the Legislature and the Governor put aside partisan politics and work together on a process enabling implementation of emergency measures, our state is likely to be one of the least prepared to respond to an upsurge of infections and deaths,” Jon Peacock, director of the Wisconsin Budget Project, warned in August.

Remembering lives lost

Duane Bark’s family carefully gathered at a funeral home to pay their respects after he died. They wore masks and kept a distance from each other, family members said.

The Barks will hold a larger celebration of Duane’s life on his birthday in July, if group gatherings are again safe.

That can only happen, Brian Bark said, “if we come together as a people and realize that we need to figure this out and get past (the pandemic).”

Harper Marten said the memorial service for her father — held virtually via Zoom — “was a bigger gift” than she expected in an era of increasing screen fatigue. Folks still shared stories and jokes about their time with Warren Shore.

“I think that COVID is really showing us that we are something much more common than the labels that divide us,” she said. “We have the opportunity and we owe it to ourselves to really connect with those (225,000 people) who passed — who meant something to somebody.”