(CNN) — It’s been called “the moment that changed everything,” the day America “turned the mystic corner,” and “the greatest political speech of the 20th century.”

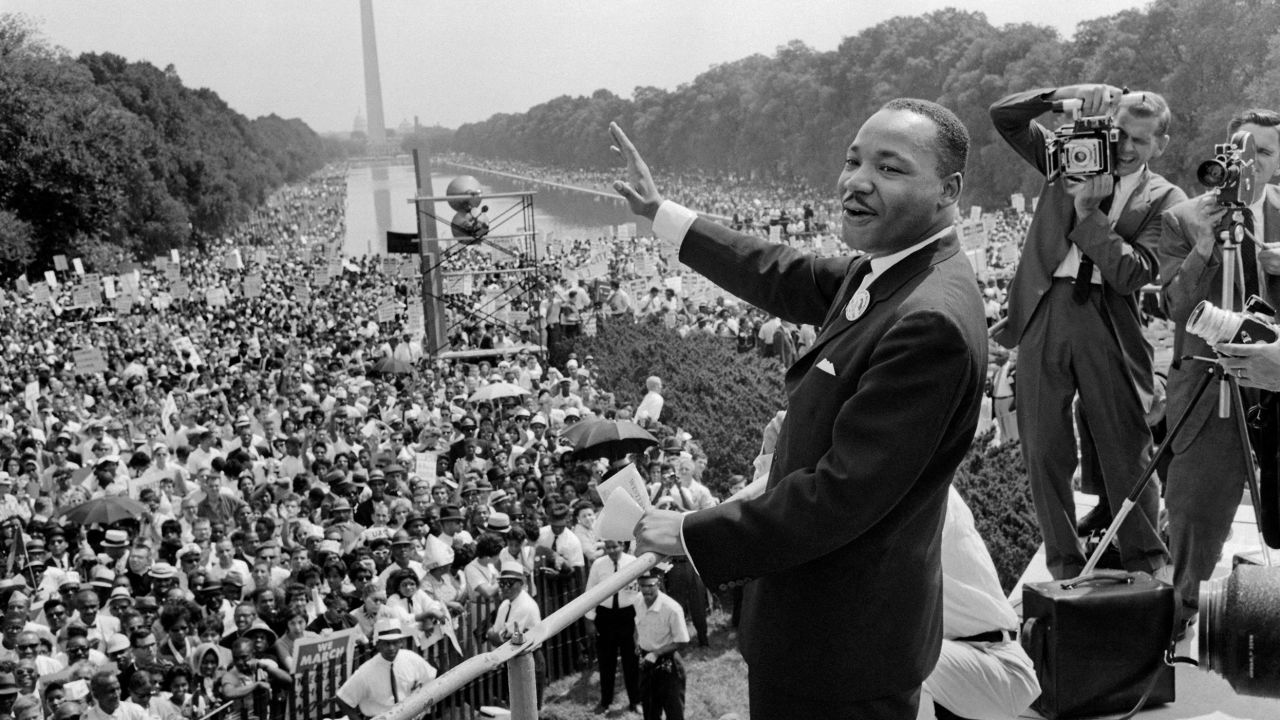

As the nation celebrates the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s national holiday tomorrow, millions of Americans will once again hear what has become the day’s unofficial soundtrack: King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

The speech King gave 60 years ago in Washington has been endlessly replayed, dissected and misquoted. It’s his most famous speech. But here’s another way to look at it:

It is also the most radical speech King ever delivered.

That declaration might sound like sacrilege to those who will point to King’s thunderous takedowns of war, poverty and capitalism in other sermons. But “I Have a Dream” has arguably become his most radical speech — not because of what he said but because of how America has changed since that day.

Forget the nonthreatening version of the speech you’ve been taught that emphasizes King’s benign vision of Black, White and brown Americans living in blissful racial harmony.

The core concept in King’s dream is racial integration — and it still terrifies many people 60 years later.

Integration is “too threatening to the status quo to ever consider fully,” says Calvin Baker, author of “A More Perfect Reunion: Race, Integration, and the Future of America.”

The concept of integration that King evoked in his “I Have a Dream” speech is the most “radical, discomfiting and transformative” idea in US politics, adds Baker, a novelist and professor at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York.

“It’s the thing the mainstream fears the most,” he says. “It’s a beautiful speech and it’s descriptive of integration. It sounds really good. And then you understand — whew — the work that’s required.”

This is the tragic irony behind King’s holiday. Millions of Americans applaud the idyllic vision of integration he depicts in “I Have a Dream.” But many of America’s schools, churches and neighborhoods remain racially segregated today — a racial status quo that people on both the left and the right have come to accept.

If that seems like an overstatement, consider this:

When was the last time you heard a prominent religious or political leader use the term “integration” while talking about solutions for racial injustice?

To King, integration meant sharing power, not just space

To understand why King’s message is so radical, it’s good to ask what he meant when he evoked integration at the climax of his speech.

At first glance, the answer seems to be physical proximity. In his speech King declared he dreamed of a day when “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood.”

But King didn’t just preach that all Americans should be able to sit at that table, historians say. He also said they should all have an equal chance at getting a slice of the economic pie being served.

“What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee,” King once said.

Historians say King never saw integration as assimilation — urging people of color to act like White people.

“He didn’t have in mind a romantic mixing of colors, or what I would call a kind of ‘rubbing shoulders and elbows’ approach to integration,” says Lewis V. Baldwin, author of “The Arc of Truth: The Thinking of Martin Luther King Jr.” “Dr . King meant mutual acceptance, interpersonal living and shared power.”

The power part is what often gets edited out during the ritualistic replays of King’s speech. There is an economic component of King’s dream that’s hardly ever mentioned. The original title of that August 28, 1963, event, for example, was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

“Integration is not just hanging out (together). It’s having access to credit, it’s seeing the value of your home increase, it’s accumulating wealth,” says Leonard Steinhorn, co-author of “By the Color of Our Skin: The Illusion of Integration and The Reality of Race.”

“It involves employment, quality education and all of those things together.”

Historians say King’s ultimate goal was not just equal economic opportunity but something even more ambitious, and even spiritual: An America where mutual mistrust between races and religions would be virtually eliminated by people living, worshiping and going to school together. They would see their common humanity and celebrate their shared identity as Americans.

“We must always be aware of the fact that our ultimate goal is integration, and that desegregation is only a first step on the road to the good society,” King said in a speech called “The Ethical Demands for Integration.”

It can all seem abstract, but Steinhorn distills what that world might look like in one pithy example:

“If an African-American knocks on the door of a White neighbor and asks for a cup of sugar, that White neighbor should see a neighbor.”

Many Americans prefer ‘virtual integration’ to the real thing

Here’s another reason why King’s dream was so radical. His concept of integration is what Baker, the scholar and author, calls “the biggest threat to the existing racial order.”

The existing racial order is still defined by one dynamic that shows little signs of changing: Many White Americans, on the left and right, refuse to stay in communities where the ratio of Black people exceeds a certain level. When non-White people arrive in larger than token numbers, Whites invariably tend to move out. Sociologists have a name for this phenomenon — it’s called a “racial tipping point.”

Although many US suburbs have grown more diverse, this stubborn dynamic is why residential and school segregation remain high 60 years after King’s speech, even though there is some evidence that racial segregation is slowly declining. It’s why Black homeowners often must hide any signs that they live in a home they’re trying to sell, because home appraisers often devalue Black-owned homes.

It’s why even some progressive White folks with Black Lives Matter signs in their lawns get angry when they’re asked to send their kids to a public school where most of the students are minorities.

This dynamic is why what looks like a racially mixed neighborhood is often one that’s on the way to becoming all-Black, says Steinhorn, who is also a professor at American University in Washington.

“Integration exists only in the time span between the first Black family moving in and the last white family moving out,” Steinhorn wrote in “By the Color of Our Skin.”

This impulse to flee communities turning Black and brown goes deeper than abstract debates over property values, neighborhood schools and freedom.

It’s deeply rooted in American history, as the late author Toni Morrison said in an interview with Time magazine.

She said every immigrant group learned that to be associated with Black people is to be associated with someone at the bottom.

“In becoming an American, from Europe, what one has in common with that other immigrant is contempt for me — it’s nothing else but color,” Morrison said. “Wherever they were from, they would stand together. They could all say, ‘I am not that.’

Steinhorn says many White Americans prefer something he calls “virtual integration.” Their primary exposure to Black people comes through TV series, movies and ads, he says. In that virtual world, King’s dream comes alive: Black, White and brown people drink beer together, trade jokes and visit each other’s homes.

To Steinhorn, virtual integration functions like a placebo: it gives White Americans the feel-good illusion that they are having repeated contact with Black people.

“With the possible exception of the military,” Steinhorn says, “the television screen may be the most integrated part of American life.”

Why some people no longer use the I-word

Here’s another irony associated with King’s acclaimed speech.

King’s potent critiques of capitalism, war and poverty were shocking at the time. He turned off allies when he called for the redistribution of wealth, argued for a guaranteed income and came out against the Vietnam War.

Those positions don’t sound so radical anymore. After the 2008 Great Recession, the failed Iraq War and polls showing a majority of young Americans now hold a negative view of capitalism, his views on those issues wouldn’t sound out of place today.

But his calls for integration have been virtually banished from public discourse. Many don’t even use the word’s close cousin, “post-racial,” anymore.

The concept of integration that King evoked has become so discredited that even many of those who believe in its goals no longer use the term.

Amanda Shaffer is one such person — and someone who says her life was enhanced by her experience with integration. She was a White student who was bused to a Black public high school in Cleveland, Ohio after refusing to follow her friends to a White private academy. She credits the experience with given giving her a level of empathy she would not have found otherwise.

“It shifted my point of view,” Shaffer told CNN in 2014 for a story about being a White minority in Black settings. “It’s like when you go to the optometrist, and they slap those new lenses on you — you see the world differently.”

Shaffer works today as a diversity consultant and a professional coach. She says she still believes in the necessity of people of different races living, working and going to school together and tries to promote those values in her work.

Still, she won’t use the term “integration” in her diversity work. She says the term “triggers” some White people.

“For me, integration is left over from all that 1950s and ’60s stuff that made a lot of people feel bad,” she says. “The problem with integration is that it feels like mixing or assimilation, and that’s where you get some of these folks who think, ‘If everybody is intermarrying and then we’re all shades of brown, where does my identity go?’ Integration is a term that pushes against people’s identity.”

Can we have a true democracy without integration?

Perhaps it only pushes against people’s identity if they define themselves by their color and not as Americans.

One reason King’s speech is so powerful is that it goes to the heart of how Americans are taught to define themselves: By adherence to a set of ideas, not by superficial physical appearances. The nation’s motto is “Out of Many, One.”

It’s no accident that King quoted from or evoked the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Gettysburg Address in his epic speech. In his telling, integration was seen as a fulfillment of the American dream — the endpoint of the pursuit of a more perfect union.

“It was the ultimate expression of the melting pot idea, that the most victimized and vilified part of American society could be integrated seamless into mainstream life, and the white majority could overcome its prejudice and welcome Black Americans as full brothers and sisters in our national community,” Steinhorn wrote in “By The Color of Our Skin.”

How many Americans still believe that is possible?

Not Baldwin, the King scholar who has spent his life studying the civil rights leader.

He talks movingly about growing up in segregated America and going to hear King speak in person two years after the civil rights leader gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. Close your eyes when Baldwin talks and his rich, honeyed Southern baritone even sounds like King.

Baldwin says the election of former President Trump, a new wave of antisemitic harassment and the rise of Christian White Nationalism has convinced him that King’s vision of an integrated America really is just a dream.

He, too, doesn’t use the term “integration” anymore.

“People tend to want to be associated with their own kind. That seems to be a natural tendency in the human spirit,” Baldwin says, adding that he questions “the full actualization of the kind of integrated society Dr. King had in mind.”

If racial integration is implausible, though, that leads to another question:

Without racial integration, can the US still call itself a democracy?

King didn’t think so, Baldwin says.

“Dr. King made it clear that integration occurs before you have a multiracial democracy,” he says. “We have to learn to live together as a single people before we can create this kind of democracy.”

Baker, the author, says the country can’t continue to give up on the dream of integration.

“When hope dies, you’re defeated,” Baker says. “If you believe that it is possible, it is in fact possible. If you stop, you’ve given up the race before it’s started. It’s hard and demanding, but it’s deeply necessary.”

Steinhorn says he puts his hope in a new generation of young Americans. The Gen-Z generation, those from the late ’90s onward, is the most racially diverse in the nation’s history. He says polls show that they are more open on questions about race, ethnicity and sexual identity than any other American generation.

“When you have a critical mass of that generation that subscribes to those principles and sets them as their North Star to be able to live in a society like that, that gives me a little bit of hope,” Steinhorn says.

King believed in hope, too.

“We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope,” he once said.

What’s the alternative to losing that infinite hope? Bill Moyers, a former White House press secretary under President Lyndon Johnson, once offered an answer while describing Johnson’s views.

“He thought the opposite of integration was not just segregation,” Moyers said, “but disintegration — a nation unraveling.”

What would that unraveling look like? It might look something like what we’ve seen in this country in recent years: The Jan. 6 insurrection, a resurgence of antisemitism, the “very fine people” marching with torches in Charlottesville, and White supremacist groups being designated as the nation’s biggest terror threat.

It may no longer be fashionable to talk about integration, but the alternative is worse:

A nation unraveling.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2023 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.