Sheng Lee Riechers remembers attending Neenah school and community events where military veterans were asked to stand and be recognized for their service to the country.

Her father, a Hmong soldier who fought communist forces under the direction of the U.S. government during the Vietnam War, would always hesitate to stand, unsure of how he would be received.

“I was like, ‘Dad, get up. You fought in the war,’” Riechers recalled. “It was always really awkward for him. I wish more people understood the history of why Hmong people are here and that Hmong people are truly American, if not more American than most Americans. They fought for the country, and they fought for freedom.”

Hmong soldiers aren’t officially recognized as U.S. veterans, but they were staunch allies of the U.S. and paid a heavy price during and after the war. Once U.S. forces withdrew from Vietnam, the victors persecuted Hmong soldiers and their families for helping the U.S.

Hmong people fled their homeland in the mountains of northern Laos for refugee camps in Thailand, where they stayed, sometimes for years, until they were resettled in the U.S., France and other countries.

Even today, Riechers’ father isn’t allowed back into communist Laos. His visa application to visit family in 2019 was denied by the government.

The denial reinforced that Wisconsin, not Laos, is home for Riechers’ family and thousands of other Hmong Americans, and their presence is expanding and enriching life here in ways unforeseen before the Vietnam War.

The 2020 census showed the Asian American population in Brown, Outagamie and Winnebago counties grew from 16,330 in 2010 to 22,189 in 2020. That’s nearly a 36% increase, compared with a 10% increase in the overall population.

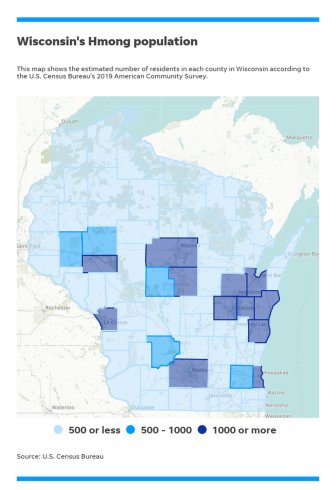

The census data released thus far doesn’t separate the Hmong American population from the Asian American population, but the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey, which is the most recent available, provides some insight.

The 2019 survey estimated Wisconsin’s Asian American population at nearly 200,000. Hmong are by far the largest Asian American ethnic group in the state, with more than 58,000 people, or 29% of the total. The next largest groups are Asian Indian (18%) and Chinese (14%).

Milwaukee County has the largest Hmong population (12,566) in the state, followed by Marathon (6,414), Dane (5,901), Sheboygan (5,675), Brown (5,027), Outagamie (4,063), La Crosse (3,402), Winnebago (3,159) and Eau Claire (3,068) counties.

The proportion of Hmong among the Asian American population exceeds 70% in Sheboygan, Marathon and Calumet counties, 60% in Eau Claire and Manitowoc counties and 50% in La Crosse, Winnebago and Outagamie counties. Brown and Portage counties are close to that level at 49% and 47%, respectively.

‘I knew they didn’t like me’

Hmong refugees arrived in Wisconsin in waves, starting in the late 1970s and ending in the mid-2000s.

Long Vue was 14 in 1980 when he arrived in Kaukauna along with his parents, three sisters and four brothers. They had planned to go to Austin, Texas, but his uncle, who was the family’s sponsor, moved to Appleton. The family was then rerouted to the Fox Cities.

Hmong refugees had few possessions and needed a sponsor to help them get a foothold.

“A refugee is in the midst of war,” Vue told USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. “You’re lucky if you survive and you’re alive. And then the next step is you are lucky if you had someone sponsor you to go to another country. Otherwise, we have people born and raised in refugee camps. They don’t have anywhere else to go.”

Vue said Hmong refugees weren’t readily accepted or understood and were bullied at school. Talking out differences or reporting the harassment to authorities was difficult because of the language barrier, so Vue learned to avoid conflict.

“The discrimination and hatred, you could feel that,” he said. “I knew they didn’t like me because they’d be yelling at me and screaming at me out in the public. I just stayed away from them and tried to live my own life, basically.”

Pao Lor, a 49-year-old Kimberly resident, was born in Laos and left as a child.

His family had sided with the U.S. during the Vietnam War. When the U.S. pulled out, his family went into hiding as part of the resistance to communist forces. His father was assassinated by the resistance after he left a hiding place to seek outside resources like rice and salt in violation of the group’s rules.

When Lor’s family fled Laos for Thailand, his mother drowned while crossing the Mekong River.

Lor spent time in the refugee camps in Thailand before arriving in Long Beach, California. In 1980, he moved to Green Bay, where his uncle had settled and the crime rate was lower.

“Many of us were 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 years old,” he said. “So for many of us, America was really our home. We could say, ‘This is going to be something where we’re going to stay for a very long time.’ Otherwise, prior to that, we were constantly moving.”

Lor graduated from Green Bay East High School in 1989, earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh and a doctorate from UW-Madison. He’s now an education professor and chair at UW-Green Bay.

Still, he doesn’t associate his life with the American Dream — that path to upward mobility in a land of equal opportunity for all. Lor at times had no idea what he was doing and was merely trying to coexist as an immigrant.

“For me, that’s what I needed to do in order to survive,” he said, “so that’s what I was going to do.”

Lor’s journey is described in his memoir, “Modern Jungles: A Hmong Refugee’s Childhood Story of Survival.”

Midwestern passive aggression

Riechers, 32, grew up in Neenah and now lives in Menasha with her husband and their 2-year-old daughter. As with the majority of Hmong Americans living in Wisconsin today, Riechers was born in the U.S.

Her parents are naturalized first-generation immigrants, arriving as refugees from Laos in the late 1970s. They first settled in Memphis, Tennessee, before relocating to La Crosse, Black River Falls and eventually Neenah. Riechers was born in Black River Falls and came to Neenah when she was 2.

“There were a lot of friendly white people in the community who embraced my family and really helped us get acclimated,” Riechers said.

She graduated from Neenah High School in 2008 and earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism and a master’s degree in business administration from UW-Oshkosh. She operated Candeo Creative, a marketing and advertising agency in Oshkosh, before being hired as Appleton’s senior communications specialist in 2020.

Riechers said northeast Wisconsin has shown a willingness to tolerate, if not welcome, people of different races. There’s hate everywhere, she said, but in the Upper Midwest, it’s a little less menacing.

“It’s a bit more passive-aggressive,” she said. “I’m not going to get in your face, but I’ll do stuff to let you know that I don’t like you.”

Riechers isn’t sure whether growing up in Neenah, which had relatively few Hmong families, was better or worse than growing up in Appleton, which had a larger Hmong population.

“It was mostly white,” she said of Neenah. “I remember our house getting egged. I can’t remember what was happening at the time because I was just a kid, but I knew from the way that the grown-ups talked and the way that my older siblings talked about it that it was racially motivated.”

The clash of cultures and races reached a climax in November 2004, after Chai Soua Vang, a naturalized Hmong American from Laos, shot eight people, killing six, in northwest Wisconsin. Vang pleaded self-defense, alleging he was confronted and shot at by a group of white hunters after unintentionally trespassing. He was convicted of six counts of first-degree intentional homicide and three counts of attempted homicide and was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

The case attracted nationwide attention. Riechers was a freshman in high school at the time.

“There was so much hate toward Hmong people,” she said. “There wasn’t really any direct targeted incidents, but I remember kids having bumper stickers that said, ‘Save a deer, shoot a Hmong.’ It was just really, really awful to have to go to school and see stuff like that.”

Resurgent racial discrimination

After a period of calm and improvement, racial discrimination against Asian Americans returned with vengeance with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020.

Then-President Donald Trump implicated Asians as the scapegoat and fueled anti-Asian animosity by repeatedly calling it the “China virus.”

Anti-Asian hate crimes quadrupled in 2021 in more than a dozen of America’s largest cities, according to an analysis from the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino.

The hostility has been felt in northeast Wisconsin.

Residents came forward last year with heart-wrenching stories of harassment and hatred to convince the Appleton Common Council to pass a resolution condemning xenophobia, racism and anti-Asian violence.

Chia Lee, an Appleton teacher, said recent hate crimes against Asian Americans make her fear for her life.

“I love to walk around the neighborhood, but I have stopped doing it because I worry about a car running over me due to my ethnicity,” Lee told the council.

Tina Thor, an Appleton native, said that while shopping for flour, a woman came down an aisle and yelled at her to “go back to your own country.”

“I was so shocked by this happening in the city where I was born and raised,” Thor said.

Asian Americans have experienced the same health concerns from the pandemic as anyone else in the community but have had the added burden of being unfairly blamed for it.

Riechers was shopping at Costco when she approached an older white man whose cart was blocking the aisle. She politely asked to pass by. “He throws up both of his hands and starts shouting, ‘Yeah, absolutely, no COVID here, no virus here,’” she said. “It was really uncomfortable. Would he have done that if anyone else had asked him to get by?”

Riechers said people oftentimes judge her as an Asian woman before they recognize her by any of her other characteristics, qualities and talents. She remains hyper aware of how the predominately white public might view her.

‘We’re not McDonalds … We’re like Tom’s Drive-In’

Lor said “pretty close to 100%” of Hmong refugees were dependent on welfare and public housing when they came to Wisconsin in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Today they not only have made a better life for themselves and their families, but they have become active, integral members of the greater community. They are educators, business owners, coaches, political leaders, friends and neighbors.

Lor, for example, supervises more than 25 professors, lecturers, staff members and adjunct instructors at UW-Green Bay.

Riechers handles communications for a city of 73,000.

Vue is the executive director of NEW Hmong Professionals, a nonprofit group that responds to the emergent needs of the community, like organizing pop-up vaccination clinics to protect against COVID-19.

Hmong people have brought diverse backgrounds, political views, business experience and community service to northeast Wisconsin. Inroads also have been made in elective office, as evidenced by Maiyoua Thao’s tenure on the Appleton council.

Vue, who has a bachelor’s degree in journalism and political science from UW-Eau Claire, acknowledges that much progress has been made toward understanding and accepting Hmong people in the past 40 years, but he doesn’t think they’ve achieved full integration. Pockets of isolation remain.

Hmong Americans still gravitate toward their own grocery stores, he said, and they still haven’t reached equality with their white counterparts in terms of job opportunities and advancement.

Lor said Hmong Americans slowly have found their footing in business and politics but have yet to reach the upper echelon in either arena. Hmong-owned businesses, he said, tend to predominantly serve Hmong populations. He thinks they are on the verge of something greater, something more mainstream.

“You can kind of compare it to, let’s say, the commercial world,” Lor said. “We’re not McDonald’s or anything like that. We’re like Tom’s Drive-In.”

Riechers said Hmong people have a history of seeking independence and freedom. They migrated from China to the mountains of Laos, Vietnam and Thailand in the 1800s after Chinese rulers sought to assimilate them and other ethnic minorities into Chinese culture.

Hmong people have a fierce independent streak that aligned with American ideals during and after the Vietnam War.

“When you think about patriotism and you think about what it means to be an American, it doesn’t really get any more American than the Hmong story,” Riechers said. “We’re immigrants. We fought for the country. We fought for freedom. Inherently Hmong are people who value their freedom.”

Expanding the collective understanding and appreciation of the Hmong American experience — much like the renewed awareness of the American Indian experience — can improve cultural competence and the ability to celebrate differences, rather than merely tolerate them or, at worst, oppress them.

That, in turn, could ease the transition for the next people — be it Afghans, Ukrainians or Congolese — who will call northeast Wisconsin home.