Through a confluence of citywide initiatives and increased federal funding for homelessness prevention, Milwaukee experienced a sharp decline in the number of individuals wrestling with home insecurity in 2020.

While the recent drop in Milwaukee’s homeless population remains consistent with a decade-long trend in Wisconsin’s largest city, Black Milwaukeeans are still disproportionately impacted by a lack of housing, and the upcoming federal eviction moratorium expiration raises concerns of a potential increase in homelessness in the coming months.

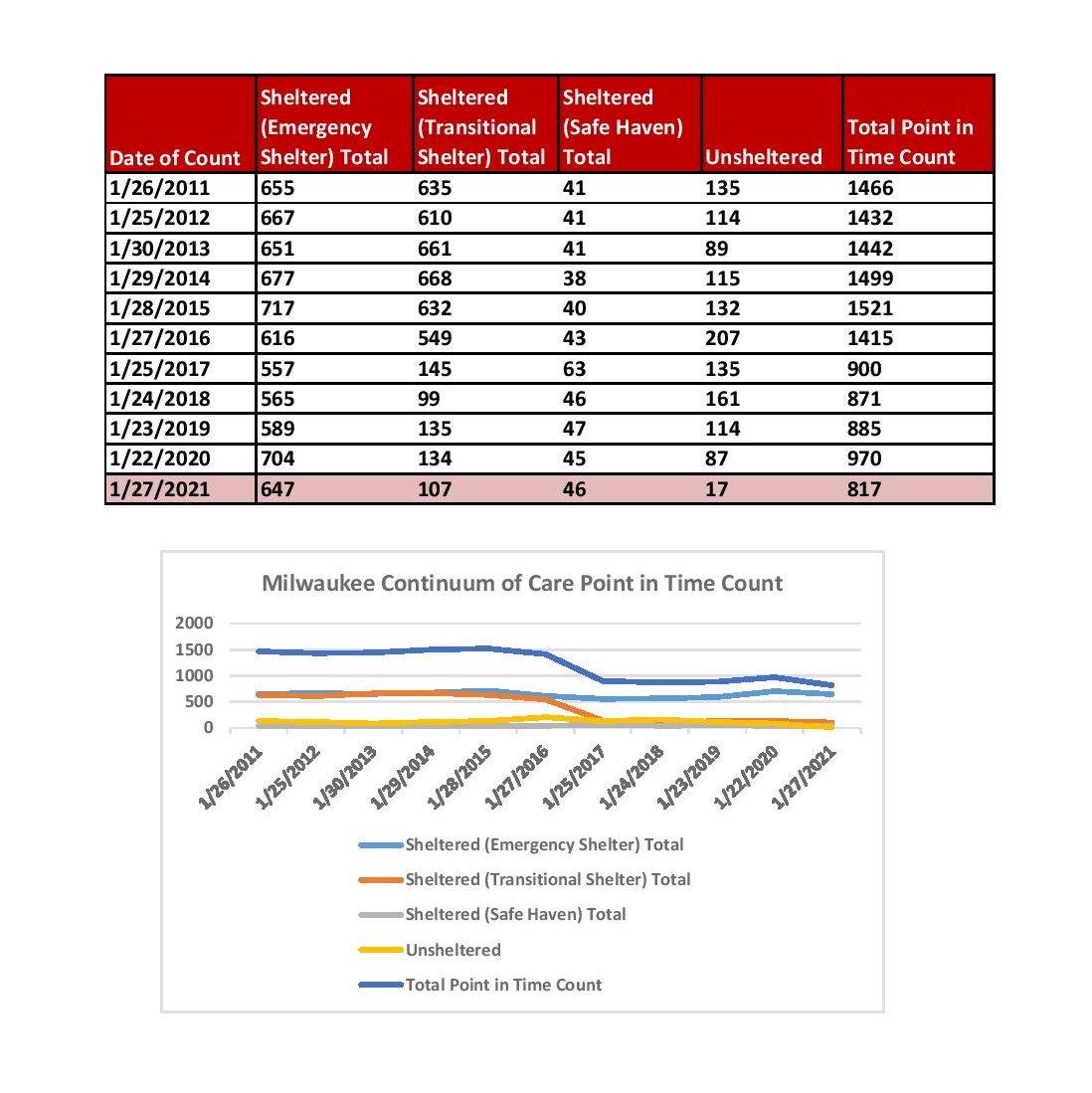

The annual Point In Time (PIT) count published by the Milwaukee Continuum of Care (CoC) recorded a total of 817 homeless people in January of 2021–down from 970 the previous year, a drop of nearly 16 percent.

The CoC PIT count measures the number of households experiencing Category One homelessness–the absence of a fixed, regular dwelling place–and divides the count into four categories: those who are sheltered in emergency lodging, those who are sheltered in transitional housing, those who are sheltered in stable safe havens and those who are unsheltered. Of the 817 homeless households recorded by the Continuum of Care, only 17 lacked shelter of any kind.

Milwaukee City and County Continuum of Care Coordinator, Rafael Acevedo, attributed Milwaukee’s falling rates of homelessness to a combination of federal aid intended to soften the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic and a concentrated effort made by the city government to slow the spread of the virus throughout Milwaukee’s homeless population.

“With additional federal support through different funding sources, we were able to open and operate three different hotels [as homeless shelters],” Acevedo said. “We didn’t want 100 beds in one big room close together. So really, that low number is attributed to the hard work of this community coming together, and we did it by working closely with our shelters, the City of Milwaukee health department and all of our wonderful homelessness providers.”

Milwaukee’s partnership with hotels and shelters is a cornerstone of the city’s 10-Year Plan to End Homelessness, a local government project launched in 2010 which Acevedo said resulted in an over 40 percent drop in citywide homelessness.

A key element of Milwaukee’s relatively successful fight against housing insecurity is its “housing first” strategy, which Acevedo said allowed the city to emphasize moving homeless individuals and families off the streets and into long term housing through leapfrogging the traditional shelter-to-housing process.

“As a community, we said we’re going to get you into housing, as soon as possible, regardless of your background, regardless if you have conviction records, regardless if you have multiple evictions from an apartment and regardless of your current health condition,” Acevedo said. “To get into an actual apartment, first you had to go into shelter, then you had to go into transitional housing, but we don’t do that any more.”

Once placed into apartments, new tenants can receive rent assistance and case management services intended to provide recipients with a smooth transition into long form housing arrangements independent of aid.

The “permanent supportive housing program,” which Acevedo said is run by the CoC in collaboration with local homeless shelters and landlords, proved successful in providing eligible Milwaukeeans with a viable pathway to sustainable housing options.

Milwaukee shetler task force chair Wendy Weckler said the city regularly managed to keep the vast majority homeless individuals and families out of the shelter system following their entrance into the program.

“At the end of the year, about 95 percent of those families stay housed either in the unit we placed them in or in a different unit of their choosing,” Weckler said. “And then at the three year mark 85 percent of those families have not touched the homeless system again.”

Weckler and Acevedo said the CoC financed its anti-homelssness initiatives through a variety of avenues, including state, local and federal funding, and said the federal eviction moratorium, implemented in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, allowed the CoC to concentrate its efforts on locating housing for the existing homeless population and bolstering its permanent supportive housing program, without fear of a growing homeless population stretching out resources.

On July 31, however, the moratorium on evictions is slated to expire, causing anxiety among shelter directors and the CoC regarding the possibility of a spike in homelessness as those who relied on federal rent assistance to remain housed lose their benefits.

“I’m really worried with the eviction moratorium coming to an end,” Weckler said. “There’s been a lot of agencies doing so much really good work, community advocate systems, so much rent assistance work to try to, you know, help people get caught up on back rent. But I think there’s just people that will still get missed, and I do worry about that.”

In conjunction with the looming threat of an expiring rent moratorium, the CoC also grappled with yawning racial disparities present in its homeless population.

According to the 2021 PIT count, 58 percent of homeless Milwaukeeans are Black, despite African Americans making up just 38.7 percent of the city’s total population. In contrast, 36.9 percent of homeless people in Milwaukee are white, yet white Americans account for 44.4 percent of the city’s entire population.

Acevedo said the disproportionate number of homeless Black Americans in Milwaukee falls in line with a larger nationwide trend, and voiced optimism at the fact that, to the best of his knowledge, the disparate Black-white homelessness rate has not grown worse in the past decade. Acevedo warned, however, of a need to invest in constructing more affordable housing if Milwaukee hopes to prevent the number of homeless Black residents from ballooning any further.

“Our numbers have been fairly consistent over time,” Acevedo said. “I think one of the barriers [to reducing Black homelessness], and one of the issues we’re having is how do we increase capacity on affordable housing? How do we improve access to affordable housing? That’s something we’re always looking at.”

Narrowing the Black-white homelessness gap will prove a daunting task for Wisconsin’s most densely populated metropolitan area should government-issued rent assistance dry up, yet hope remains in some circles for a prolonged partnership between local governments and Washington in order to combat homelessness.

Weckler said she hopes the past year’s government intervention into rental assistance will shift federal priorities and usher in an era of heightened interest in providing access to affordable housing to low-income neighborhoods.

“I would say the good that comes out of COVID, which isn’t much, is that the federal government has designated a lot of funds specifically for housing people and keeping people in housing,” Weckler said. “So, there are a lot more resources available. As always, it’s really challenging to find apartments for our people.”