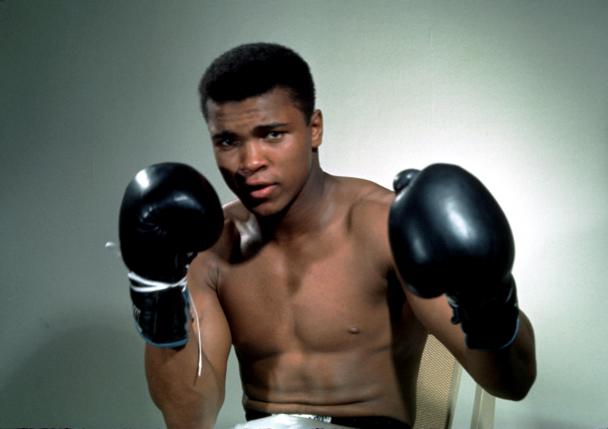

Former world heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali, whose record-setting boxing career, flair for showmanship and political stands made him one of the best-known figures of the 20th century, died on Friday aged 74.

Ali, who had long suffered from Parkinson’s syndrome which impaired his speech and made the once-graceful athlete almost a prisoner in his own body, died a day after he was admitted to a Phoenix-area hospital with a respiratory ailment.

Even so, Ali’s youthful proclamation of himself as “the greatest” rang true until the end for the millions of people worldwide who admired him for his courage both inside and outside the ring.

Along with a fearsome reputation as a fighter, he spoke out against racism, war and religious intolerance, while projecting an unshakeable confidence and humor that became a model for African-Americans at the height of the civil rights era.

“Muhammad Ali was one of the greatest human beings I have ever met,” said George Foreman, who lost to Ali in Zaire in a classic 1974 bout known as the “Rumble in Jungle.”

“No doubt he was one of the best people to have lived in this day and age. To put him as a boxer is an injustice.”

Ali enjoyed a popularity that transcended the world of sports, even though he rarely appeared in public in his later years.

“We lost an icon,” said Delson Dez, 28, a construction worker, who was holding up a poster of the fighter in Scottsdale, Arizona soon after Ali’s death was confirmed in a statement issued by his family late Friday evening.

Few could argue with his athletic prowess at his peak in the 1960s. With his dancing feet and quick fists, he could – as he put it – float like a butterfly and sting like a bee. He was the first person to win the heavyweight championship three times.

But Ali became much more than a colorful and interesting athlete. He spoke boldly against racism in the ’60s, as well as the Vietnam War.

During and after his championship reign, Ali met scores of world leaders and for a time he was considered the most recognizable person on earth, known even in remote villages far from the United States.

Ali’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s came about three years after he retired from boxing in 1981.

His influence extended far beyond boxing. He became the unofficial spokesman for millions of blacks and oppressed people around the world because of his refusal to compromise his opinions and stand up to white authorities.

“We lost a giant today. Boxing benefited from Muhammad Ali’s talents but not nearly as much as mankind benefited from his humanity,” said Manny Pacquiao, a boxer and politician in the Philippines, where Ali fought arch rival Joe Frazier for a third time in a brutal 1975 match dubbed the “Thrilla in Manila.”

In a realm where athletes often battle inarticulateness as well as their opponents, Ali was known as the Louisville Lip and loved to talk, especially about himself.

“Humble people, I’ve found, don’t get very far,” he once told a reporter.

His taunts could be brutal. “Joe Frazier is so ugly that when he cries, the tears turn around and go down the back of his head,” he once said. He also dubbed Frazier a ‘gorilla’ but later apologized and said it was all to promote the fight.

Once asked about his preferred legacy, Ali said: “I would like to be remembered as a man who won the heavyweight title three times, who was humorous and who treated everyone right. As a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him … who stood up for his beliefs … who tried to unite all humankind through faith and love.

“And if all that’s too much, then I guess I’d settle for being remembered only as a great boxer who became a leader and a champion of his people. And I wouldn’t even mind if folks forgot how pretty I was.”

Ali was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on Jan. 17, 1942, as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., a name shared with a 19th century slavery abolitionist. He changed his name after his conversion to Islam.

Ali is survived by his wife, the former Lonnie Williams, who knew him when she was a child in Louisville, along with his nine children.