Through Black History Month, Madison365 will publish stories from the History of Black Madison, provided by National Guardian Life Insurance Company. Today: The Musicians.

Give the drummer some

Clyde Stubblefield was already famous when he arrived in Madison in 1971. The “Funky Drummer” had toured the world with James Brown and had laid down a drum beat that would become the most sampled of all time — and for which he’d never be properly compensated.

Having visited Madison on tour, and having a brother who lived here, he decided to settle here and never really sought the national limelight. He became a staple of the local music scene, though, and the national limelight sought him. His innovative style was recognized in 1990 when he was named Drummer of the Year by Rolling Stone. In 2014, LA Times named him the second-best drummer of all time, and in 2016, Rolling Stone again honored him, putting him in the top 10 of all time.

From the early 1990s to 2015, he performed on the nationally syndicated public radio show “Michael Feldman’s Whad’Ya Know” on Wisconsin Public Radio. He also performed every Monday night downtown Madison with The Clyde Stubblefield Band for many years.

In 2000, he was inducted into the Wisconsin Area Music Industry Hall of Fame. In 2004, he received the lifetime achievement award at the Madison Area Music Awards. Madison Mayor Paul Soglin declared Oct. 10, 2015, Clyde Stubblefield Day. His drumsticks are part of an exhibit in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

On the 1970 James Brown song “The Funky Drummer,” Stubblefield improvised a drum break that’s estimated to have been sampled more than 1,500 times by acts like Public Enemy, N.W.A, LL Cool J, Run-DMC and the Beastie Boys, and later pop musicians such as Ed Sheeran and George Michael. Because he was not given songwriter credit on the track, however, Stubblefield did not receive any royalties for those samples.

His first solo album, Revenge of the Funky Drummer, came out in 1997, followed by two more solo albums and many collaborative projects.

After Stubblefield died in 2017, The University of Wisconsin honored him with a posthumous honorary doctorate.

“It is impossible to overstate the impact Stubblefield has had on the world of drumming,” said UW-Madison Professor of Percussion Anthony Di Sanza in a letter nominating Stubblefield for the degree. “He has inspired generations of drummers with his syncopated, yet flowing rhythmic grooves that combine effortlessly with his unique musical taste and sensibility. For many of us living in the world of drums and percussion, he is a trailblazer and a hero.”

The Venues

The same year that Stubblefield arrived in Madison, Roger Parks opened a bar on the south side — Mr. P’s — which became virtually the only place to hear live jazz in Madison for years. It also became the “war room” for Roger’s son Eugene, who would later become the City of Madison’s affirmative action officer and launch a years-long campaign against the city — including federal lawsuits and two campaigns for mayor — after being fired in 1988.

Mr. P’s lasted until 1998 and overlapped with another effort to create a venue for jazz closer to downtown. Sax player Hanah Jon Taylor, recently relocated from Chicago, opened House of Soundz on Williamson Street in 1994, but it only lasted two years. Undeterred, Taylor opened Madison Center for Creative and Cultural Arts in 2003, which operated until 2007. A decade later he opened Cafe Coda inside The Fountain on Dayton Street as a space where both longtime practitioners of jazz, students of jazz, and appreciators of the genre can gather to learn and listen in community. A year later he moved back to Willie Street, opening the new Cafe Coda in September of 2018. It’s still going strong, thanks in part to community support to survive the pandemic.

Mr. P’s lasted until 1998 and overlapped with another effort to create a venue for jazz closer to downtown. Sax player Hanah Jon Taylor, recently relocated from Chicago, opened House of Soundz on Williamson Street in 1994, but it only lasted two years. Undeterred, Taylor opened Madison Center for Creative and Cultural Arts in 2003, which operated until 2007. A decade later he opened Cafe Coda inside The Fountain on Dayton Street as a space where both longtime practitioners of jazz, students of jazz, and appreciators of the genre can gather to learn and listen in community. A year later he moved back to Willie Street, opening the new Cafe Coda in September of 2018. It’s still going strong, thanks in part to community support to survive the pandemic.

All about that bass

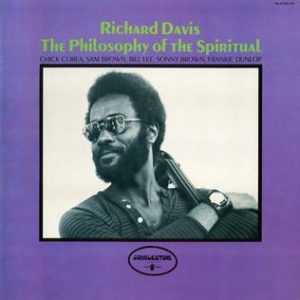

Another giant of Madison’s jazz scene was also a transplant, who arrived in 1977. Like Stubblefield, bassist Richard Davis was already world-renowned when he came to Madison. Starting in the 1950s, he became one of the best-known and most in-demand studio and performance bassists in the world. He recorded with folk, jazz, and rock artists from Miles Davis to Van Morrison to Bruce Springsteen, and he also performed under Igor Stravinsky, Leonard Bernstein, and many others.

Another giant of Madison’s jazz scene was also a transplant, who arrived in 1977. Like Stubblefield, bassist Richard Davis was already world-renowned when he came to Madison. Starting in the 1950s, he became one of the best-known and most in-demand studio and performance bassists in the world. He recorded with folk, jazz, and rock artists from Miles Davis to Van Morrison to Bruce Springsteen, and he also performed under Igor Stravinsky, Leonard Bernstein, and many others.

A Chicago native, he decided it was time to return to the Midwest and begin to pass on his knowledge and experience to the next generation. He finally relented to the incessant recruiting of the University of Wisconsin, joining the music faculty in 1977.

“I should be careful what I say” about his first impressions of Madison, he said with a gravelly chuckle in a recent interview. “It was kind of laid back and slow. Different rhythm. I had to regroup and lessen my expectancy. [The students] didn’t know anything. They didn’t know about jazz. They never answered any questions I asked them. They didn’t know anything.”

Peter Dominguez, one of Davis’s first students, helped him launch the Richard Davis Foundation for Young Bassists, an independent nonprofit organization that hosts an annual conference where young bass players, ages 3 to 18, can learn from and perform with masters from around the country. Around the same time that nonprofit was getting started, Davis started another effort to solve another, bigger problem — racism in liberal Madison.

“People say Madison is very liberal. It’s not,” Davis says. “I saw a need for change.”

He heard a radio show about racial healing classes and thought it was a good idea. He got some training himself and ran a weekly class for more than 25 years.

He says things have changed a bit, noting especially that the UW’s Mead Witter School of Music has more faculty of color. But that’s not enough.

“Still racism going on,” he said. “I keep in touch with people [on campus], and they tell me what’s happening and what’s not happening.”

But he also knows quick change was never a realistic goal.

“When I first came here 40 years ago, in ’77, I met people who had come here 20 years before I got here, and they said nothing had changed since they were there,” he said. “Racism is not an easy thing to wipe out. It perpetuates itself all the time. School systems remain the same, administration remains the same. You don’t see changes that are rapid.”

So you just have to be patient?

“You can be patient all you want to,” he says with a chuckle. “That isn’t gonna do anything either. But you have no other choice.”

Now 90, Davis has a street named in his honor on Madison’s east side.

Gettin’ fresh

Right around 1984, a group of Madison West students started performing original rap and hip-hop tunes at local talent shows. Erin “DJ Sweet E” Hynum, Johnny “Savior Faire/J-Law” Winston Jr., Emanuel “MC Yokes” Whitfield, Oren “Finesse” Ben-Ami, and Richard “Daddy Rich” Henderson would become Fresh Force, the first Madison-based hip-hop act to be signed to a national record deal.

“The hip hop scene, the urban music scene in Madison was pretty sparse at that time,” Winston said in a recent interview. He recalled the group’s first 45 EP as “a big deal.” Recorded in 1987 by Butch Vig at Smart Studios (the same studio that would later produce Nirvana’s seminal album Nevermind), the record included the tracks “We Rock the House”, “Always Together”, and “Prejudice.”

Fresh Force performed regularly around Madison, Milwaukee and Chicago and appeared in commercials for American TV, as well as the 1990 census and other local agencies.

“I mean, we rapped about everything,” Winston said with a laugh.

“We were pretty local and we had a good time doing what we’re doing and I wish we had the technology that the young people have today,” he said, such as SoundCloud, Spotify and YouTube.

Fresh Force got national airplay and distribution after they signed with Chicago-based record label DJ International. They also shared the stage with some huge names, performing with and opening for such artists as Speech (from the Grammy-winning group, Arrested Development), Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam, Ready for the World, EPMD, Glenn Medeiros, The Cheaters, and Fast Eddie.

“It was just five guys having a whole lot of fun together and making some cool music and stuff we can still talk about today,” Winston said.

“Everybody grew up” by 1992 or so, and the group’s performance career faded as the members embarked on other careers. Winston became a Madison firefighter and school board member. Hynum became owner of The Underground (a music venue where Fresh Force, ironically, never performed) and now works as a chief financial officer. Henderson owns a custom t-shirt company.

Winston fondly remembers those days, and said it’s important to remain connected to your hometown.

He said he’d advise any young artists to “perform as much as they can. Record as much as they can and use the mediums that they have at their disposal. The SoundClouds, the YouTubes, again all this stuff we didn’t have, the internet and everything else,” he said. “But what really makes an artist is people in their own hometown relating to them. If you have a buzz in your own hometown, that’s a great thing. So people who live in Madison, they shouldn’t forget Madison, they shouldn’t forget to make a name for themselves here and have a whole lot of fun doing it.”