(CNN) — It’s one of the most well-known public service announcements in American history.

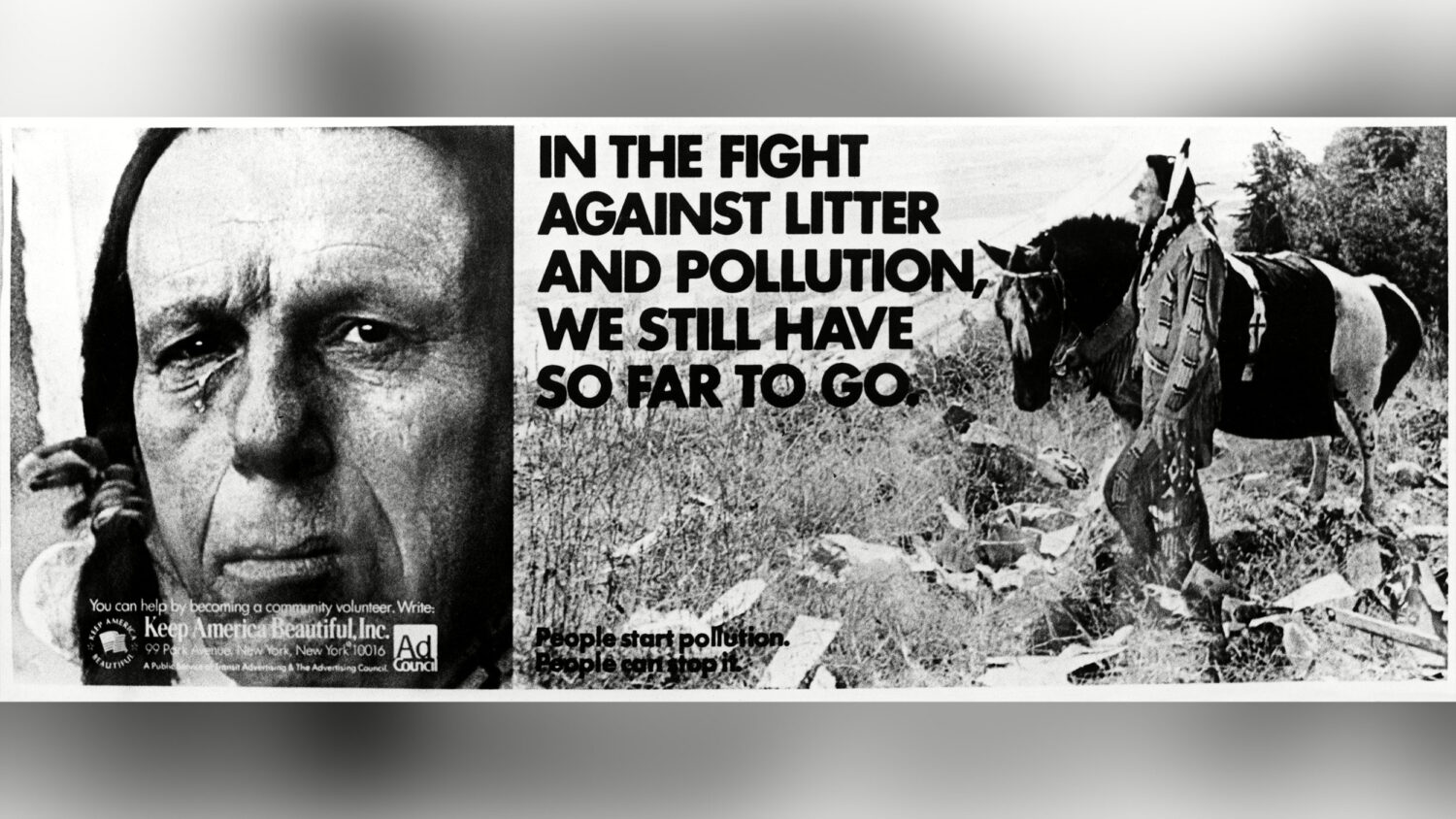

A Native American man in buckskin and braids canoes through a polluted river, past smoke-emitting factories and onto a littered shore. Trash hurled from the window of a passing car lands at the man’s feet. As the camera closes in on his face, a tear rolls down his cheek.

“Some people have a deep abiding respect for the natural beauty that was once this country,” a voiceover proclaims. “And some people don’t.”

The commercial first aired on television on Earth Day in 1971, and left a lasting impression on viewers. The “Crying Indian” (who incidentally was portrayed by an Italian American) became a symbol in an environmental movement that urged everyday people to do their part in addressing pollution. Over the years, it’s been parodied on TV shows such as “The Simpsons” and “King of The Hill.” But for all its impact, the ad has a fraught history.

Last week, Keep America Beautiful, the organization behind the commercial, announced that it would be retiring the “Crying Indian” ad and transferring the rights to the National Congress of American Indians Fund.

“The advertisement, which became synonymous with furthering environmental protection and awareness in popular culture at the time of its creation, was later known for featuring imagery that stereotyped American Indian and Alaska Native people and misappropriated Native culture,” said a news release about the move.

Here’s a look at the ad’s complicated legacy.

The ad appropriated Native culture

The “Crying Indian” ad effectively exploited American guilt over the historical treatment of Indigenous people in order to spur individuals into action. The man at its center, however, was not a Native American, but rather an Italian American who went by the name of Iron Eyes Cody. Born Espera Oscar de Corti, Iron Eyes Cody built a career off portraying Native characters in Hollywood Westerns and also presented himself as Native in his real life.

Keep America Beautiful’s commercial depicts the “Crying Indian” as a relic of the past — a silent and stoic figure dressed in stereotypical garb. But at the time of its release, real Native activists were occupying Alcatraz Island and drawing attention to issues of sovereignty and land rights, as historian Finis Dunaway noted in his book “Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images.”

Keep America Beautiful’s decision to center a Native American character in its anti-pollution campaign was also strategic, according to Dunaway. The group seized upon a phenomenon in the counterculture, which at the time was co-opting elements of Native identity as a rejection of mainstream American values.

“In promoting this symbol, Keep America Beautiful was trying to piggyback on the counterculture’s embrace of Native American culture as a more authentic identity than commercial culture,” Dunaway wrote in a 2017 opinion piece for the Chicago Tribune.

CNN has reached out to Keep America Beautiful and NCAI for comment.

In a statement, NCAI Executive Director Larry Wright, Jr. said the ad would be used only for educational purposes.

“NCAI is proud to assume the role of monitoring the use of this advertisement and ensure it is only used for historical context; this advertisement was inappropriate then and remains inappropriate today,” Wright said. “NCAI looks forward to putting this advertisement to bed for good.”

Critics call out greenwashing

Critics have also accused Keep America Beautiful of greenwashing through its iconic “Crying Indian” ad and other campaigns.

The organization formed in 1953 when “a group of corporate and civic leaders met in New York City to bring the public and private sectors together to develop and promote a national cleanliness ethic,” according to its website. Those leaders came from packaging and beverage corporations such as the American Can Company, the Owens-Illinois Glass Company and later Coca-Cola and the Dixie Cup Company, Dunaway wrote in his book.

Through various ad campaigns in the late ’50s and ’60s, Keep America Beautiful promoted messages about a growing litter crisis and urged citizens to keep parks and outdoor spaces clean. In doing so, critics noted, the organization shifted the public conversation away from the actual sources of litter — the growing numbers of disposable containers produced by beverage companies.

Environmental activists at the time were drawing attention to the container industry’s role in pollution, highlighting the issue in many Earth Day demonstrations in 1970, Dunaway wrote. It was in that context that the “Crying Indian” ad debuted in 1971.

“In creating the image of the Crying Indian, KAB practiced a sly form of propaganda. Since the corporations behind the campaign never publicized their involvement, audiences assumed that KAB was a disinterested party. KAB documents, though, reveal the level of duplicity in the campaign,” Dunaway wrote in his book.

“Disingenuous in joining the ecology bandwagon, KAB excelled in the art of deception. It promoted an ideology without seeming ideological; it sought to counter the claims of a political movement without itself seeming political. The Crying Indian, with its creative appropriation of countercultural resistance, provided the guilt-inducing tear KAB needed to propagandize without seeming propagandistic.”

The ad deflected responsibility for pollution from corporations onto individuals and “concealed the role of industry in polluting the landscape,” Dunaway wrote. While environmental groups such as the Sierra Club and the Wilderness Society supported the ad upon its release, several of them resigned from the advisory board of Keep America Beautiful after its leaders publicly opposed bottle deposit legislation, Ginger Strand reported for Orion magazine.

But as the cracks in the group’s mission became clear, the beverage industry had shifted to primarily manufacturing disposable containers. And as Dunaway noted, the emphasis on individual action instead of corporate practices in the conversation around climate change persists today.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2023 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.