The New NFL Policy released requiring all NFL players to stand if they’re on the field during the National Anthem reminds us that sports leagues want black bodies and not black voices. It reminds us that heavier pockets have heavier influences, but this is nothing new to us. The trend of punishing black athletes for peacefully protesting leaves us reminiscent of another anthem protester, this time in the NBA, who faced the same challenges as Colin Kaepernick and many other NFL athletes who are threatened to be fined and blackballed from their respective leagues. Former Denver Nuggets player Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, uses his identity as a black man and a Muslim to advocate for his message of justice and action. Abdul-Rauf was suspended for refusal to stand during the Anthem more than 20 years ago.

Last month, Abdul-Rauf visited Madison as part of UW-Madison’s Muslim Student Association’s (MSA) Islam Awareness Week.

“It’s important to highlight the achievements and unique aspects of the Muslim culture, whether it’s within the Madison community or abroad,” said MSA President, Razan Aldagher.

MSA partnered with the Black Cultural Center bringing in Abdul-Rauf through the Madison-based agency Book A Muslim (BAM), which looks to break barriers and give accurate representation of the Muslim American experience.

“Mahmoud gave up $33,000 per game and he threw it out the window because of his values, because of social justice,” BAM cofounder Syed Umar Warsi said. “Mahmoud is the epitome of believing in yourself, believing in your faith, and being unapologetic about it without the title.”

“Over twenty years ago, I made the decision to cut my career short. Every decision we make has a context. Understanding the context, I may not have done it the way he [Kaepernick] did it, but I understand,” said Abdul-Rauf.

Abdul-Rauf, formerly known as Chris Jackson, shared his context and legacy, reflecting on his life growing up poor in Mississippi and how that shaped his ethics, both moral and work-related.

“My mother wanted so desperately for her children to be educated,” he said. “Growing up in that environment [Mississippi] I didn’t have confidence academically. I knew I wanted to do something with myself and that was to play basketball…It was bigger than me. I wanted to get my mother out of poverty. I would watch people in other countries starving on the television. I would be crying with my heart. I asked God to put me in the position to help people like that one day.”

“I came from a background of praying for somebody more than just yourself. Any time we try to be great at something it’s always something bigger than ourselves…I remember watching Roots. The scene with Kunta Kinte where they said ‘behold something greater than yourself.’”

Abdul-Rauf’s work ethic came as early as the age of nine through his obsession with basketball. He would play through the blistering cold, rainy thunderstorms, and unforgiving heat, just to make that last basket, fueled by cups of coffee, sugar water, and syrup sandwiches. His work ethic continued throughout high school and into his days at LSU and eventually the NBA. His interactions with others would shape and humble him into the man he was becoming.

“I started getting arrogant,” he said. “One day this older guy cursed me out worse than I’ve been cursed out in my life. I didn’t let it know it hurt my feelings. I said ‘from this day forward, I’m never going to let my emotion take ahold of me.’ It started opening doors.”

He remembers being the number one guard in the nation in 11th grade when Michael Jordan was in Princeton talking to his team. Jordan prompted Abdul-Rauf to score on him, which he did. Twice.

His career at LSU lead him to set the record for a freshman with 53 points. And while confident on the court, he left doubting himself more than ever before.

“Our belief is sometimes mixed with doubt. It’s passing through my mind because I’m getting closer. Things like this don’t happen to people like me,” he said.

By people ‘like him’ he was referring to his background as a socially disadvantaged black youth as well as his Tourette’s Syndrome, which went undiagnosed until the 11th grade.

Growing up in Mississippi along with his tourettes created an inferiority complex within himself.

“When Dale Brown gave me that book on Malcolm X, I started reading,” he said. “He had things that I had that I want. His articulation. His courage. Growing up in the 70s and 80s in the south (Mississippi) seeing the KKK…I would see things I knew that was wrong, but I was afraid to do something about them. I told myself I don’t want to live like this, it ain’t natural. I want to live with a free conscience and a free soul and I don’t care if people like it or not. I got to work to break these chains.”

He and his friend would talk about everything from politics to spirituality, which set the stage for him finding his faith.

“We were going along and Islam came up into question. We went picked up the Qur’an and opened it up, I don’t remember the page, I don’t remember what I read…” He trailed off. “Whatever I read in that book, I said this is it for me. I talked to this African American brother and he would put me up on knowledge.”

“As I began to meet people, how Muslims are, they started embracing me whenever they heard I was coming to a city,” he said. “Every city I went to. After the game, all we’re doing is talking about issues, political issues, social issues. The first book I ever finished in my life…The Qur’an. First trip I took overseas was to Hajj (the pilgrimage to Mecca that Muslims take).”

The more Abdul-Rauf read and educated himself, the more uneasy he became about the narrative that he once believed about himself.

“I think the worst thing you can do to a human being is to deny them the knowledge of self,”he said. “No wonder I could never truly embrace success because of what society was telling me. I’m not going to be that person. The most revolutionary thing you can do is educate yourself.”

“I’m starting to hear about things that are happening. Jim crow, systemic racism, why things are the way they are. You gotta take a position. No neutrality.”

“Then I’m reading the Qur’an, verses like ‘For you who are steadfast in your commitment,’ and ‘Enjoin good and forbid evil,’ God didn’t put in a human being two hearts. The Quraysh was a super power the same way the United States is a superpower.”

The Quraysh were the powerful tribe of Meccans who persecuted the first Muslims, in order to silence them from spreading their message.

“You have to make an institution of justice. Go public with this deen (creed). You act upon the knowledge you have and insha’Allah (God willing), Allah will show you the rest.”

After analyzing his beliefs regarding his faith and dedication to justice, Abdul-Rauf began his silent, peaceful protest by refusing to stand for “The Star Spangled Banner”.

Abdul-Rauf quickly mentioned when the media sat him down to ask him what his views on the American flag were.

He replied saying he believes it stands for tyranny and oppression, pointing out that he does not think everything in America is bad.

The Nuggets general manager gave him the ultimatum: Stand for the flag or face suspension. Abdul-Rauf took the suspension, but eventually compromised after hearing an impactful story.

“I ended up talking to this scholarly brother,” he said. “He gave me an example of the Prophet Muhammad. He was sitting down when a Jewish funeral procession passed by. There was friction within the communities. They pass by and his companions asked ‘Why are you standing?’ He said ‘I’m not standing for their cause, I’m standing because Allah gave and took a life.’”

“I decided to come back. The first thing I thought they would say is that I would compromise. I said I still feel the same way, but they wanted to make an example of me,” he said.

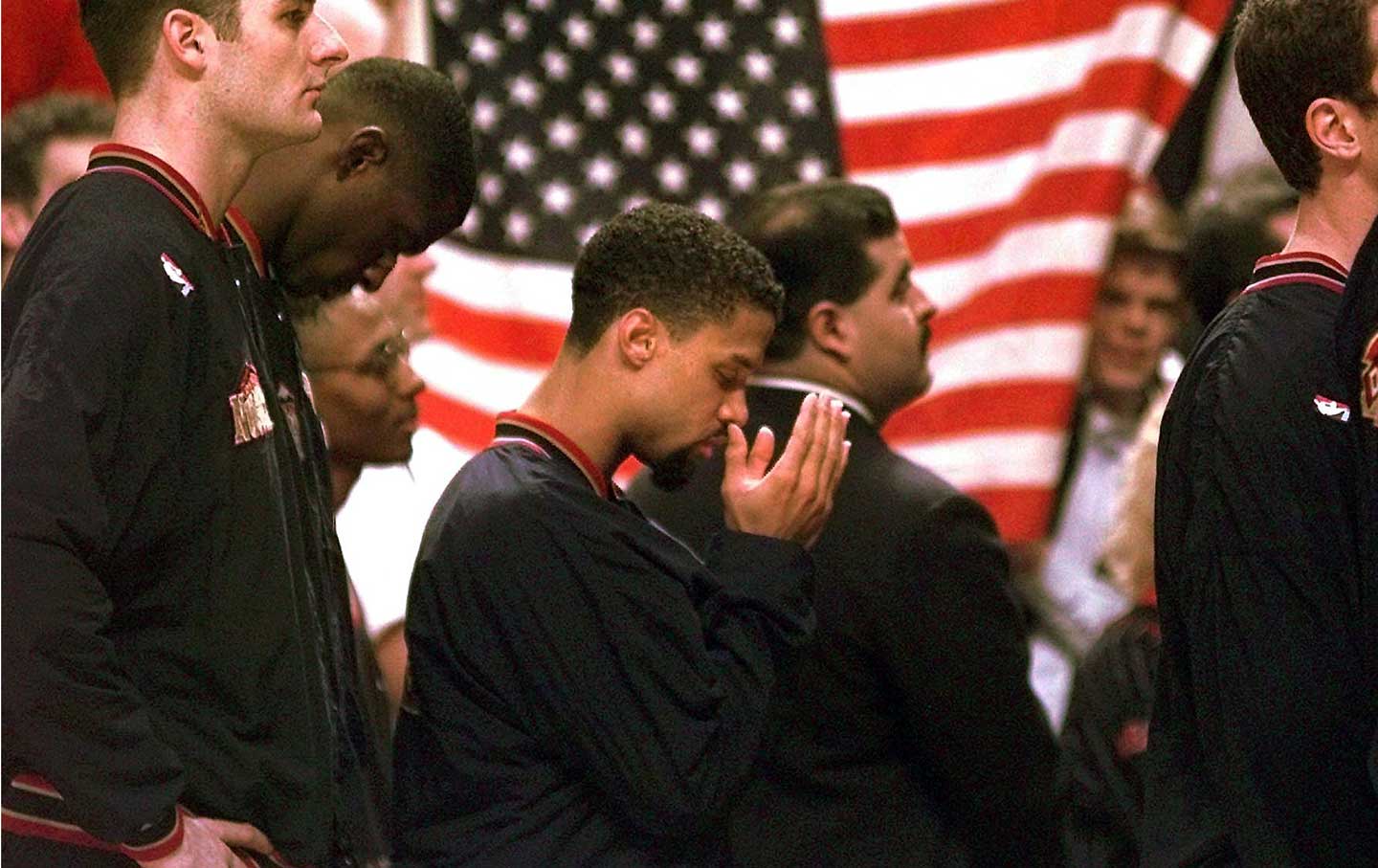

Abdul-Rauf returned to the court and stood during the anthem, but instead of his hand on his heart, he had his head down, facing his palms, making an Islamic prayer called Du’a. He had a history of praying for other people and praying for justice came from his childhood.

“They didn’t know that I’m fighting for them too. For the homeless, for proper medical care,” he said. “Justice is not something just for Muslims, it’s for anybody going through these conditions.”

He found inspiration in the words of civil rights leaders of the past and their causes, many of which are still being fought for today.

“I think about MLK and how an injustice anywhere is an injustice everywhere,” he said. “I think about Huey P. Newton and that to commit revolutionary suicide is not that we have a death wish, but it’s that the need to live in dignity and peace is impossible to live without it…but when resistance becomes fashionable, it loses its force,” he said, noting the desensitization that comes in normalizing these movements.

“It’s communicative action. How many times have you heard when you’re protesting to be calm? You beat me upside my head and I’m supposed to have dialogue with you. Groups like the black panther said we’re not going to be comfortable with you. When you suggest rage, it forces people to pay attention to you. God gave us anger. If it wasn’t for anger, you wouldn’t feel repulsed by injustice.”

Today we see exactly what Abdul-Rauf was (and is) so passionate about, injustice in the judicial system, police brutality, and people repulsed by widespread injustice. The NFL players face consequences even with peaceful protests. Abdul-Rauf’s athletic career took a blow from his choices as did Kaepernick’s. As we continue to see history repeat itself through athletes, it’s clear that the black body is a prized possession when it does what many leagues want while the black voice is a dangerous weapon in all facets of life.