Today, a new exhibit is being opened to the public at the Chazen Museum of Art on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus. The culmination of multiple years of research and planning, the UW-Madison Public History Project exhibit looks to ask questions about the real history of UW-Madison itself. The Public History Project looks to give voice to a lesser-known history of UW-Madison through students, staff, and associates of the university who have been affected by marginalization across identities.

Kacie Lucchini Butcher, Director of the Public History Project, was brought on to the project in 2019 and worked collaboratively with students to research in archives and do oral history interviews to gather perspectives on the university that are often unheard or forgotten. Although COVID changed the approach to the work, it did not halt Lucchini Butcher and the research team from reaching this point of the exhibit’s release.

“As a research project, being locked out of the archives for five to six months is untenable,” Lucchini Butcher said. “We were looking at histories that have never been documented before. We couldn’t just go get a book from the library. These things have literally never been researched before…We tried to organize it chronologically. What if it’s one huge timeline of UW? Then it got really hard quickly, because at the same time that housing discrimination was happening, the color line and UW athletics was happening, and the gay purges were happening. We were like, ‘How will people focus?’ You’ll be jumping from purges to athletics back to housing. We decided, instead, to go with this thematic approach.”

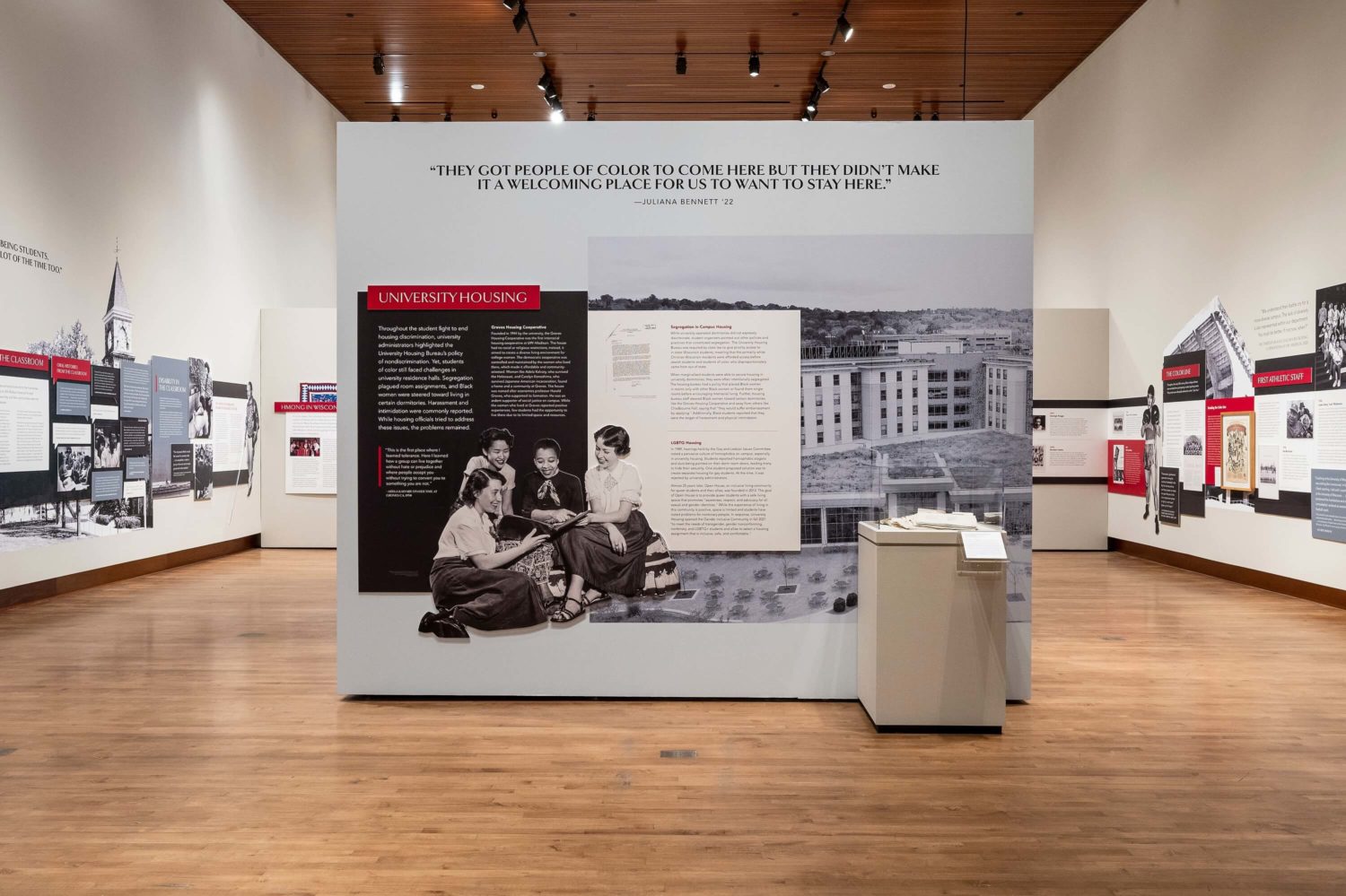

Themes of the Public History Project include topics such as housing, athletics, Greek life and the effects of gender and sexism at the university. The research team members were able to gather these stories through campus archives by intentionally looking to fill in the blank spaces left in more popular historical perspectives.

“Students don’t think of themselves as historic,” Lucchini Butcher said. “They don’t think of the work that they’re doing as being of historical value. The people who do see their work as historically valuable such as presidents, the Chancellor, and deans have these really extensive collections. You get this really high-level view of what’s going on, but you don’t always get this grassroots-level view of the institution. The research was primarily the most difficult because we’d get fragmented stories or only pieces.”

The fragments and pieces resulted in a full and vivid picture of experiences, stories, and resistance expressed and recorded through the voices and actions of those who did experience the darker side of UW. The history in the archives proved to be emotionally taxing, but not unfamiliar to sentiments felt in the present. The Public History Project also makes use of interviews done by the research team since 2019 as a form of oral history by incorporating the recollections and recommendations of people from marginalized backgrounds who were involved with the university.

“I think generally, one of the things that was really positive foresight on the part of the university administration in setting up this project, was that the project does not report to UW administration,” said Lucchini Butcher. “The project reports to a steering committee of faculty, staff, students and community leaders. They have the final say on the exhibit and what we’ve published. The university didn’t get to come in and say, ‘You don’t get to do that.’ They set it up that way, because they wanted myself and our researchers to have academic freedom to be able to take this honest look at the university’s past without the pressure of the university trying to protect itself. And I think that setup gave us a lot of credibility with the community as well.”

The importance of facing the harsh reality in the history of the university reflects the very purpose that the project itself was commissioned by UW administration in 2017. The weight of a history marred by racism, sexism, homophobia, and many other marginalizing structures is sure to be heavy for many. However, Lucchini Butcher was positive that there was also plenty of good to be found in both the efforts of students in the past, and the efforts of students in the present.

“I like to be really clear that for every terrible history that we studied, there was an equal positive history somewhere in that archive,” Lucchini Butcher said. “Because people are pushing back and finding community. They’re finding joy and hope, right there…I think the strength of using students was that our students care about this institution, and they chose to go here. They’re really passionate about it. I actually think that the close connection of being a student of this place, meant that students felt a lot of ownership over wanting to tell this history, and wanting to tell new stories about UW.”

What came of the students’ efforts is an experience and learning opportunity that is sure to leave its mark on many for the coming semester. The exhibit itself is a beautiful collection of photos, quotes, stories, and informative histories that highlight the voices and experiences of those often left behind in the collective imagination of UW-Madison. Those looking to check out the exhibit will also have the chance to make their own voice heard through interactive elements in the exhibit that allow people to reflect and question the university, other students, and themselves. Giving the exhibit a chance is a great first step to challenging the lack of attentiveness paid to these histories, and stepping inside the Chazen Museum to check it out is Lucchini Butcher’s only request.

“The hope for me, the base hope, is that I just want people to go (see the exhibit),” Lucchini Butcher said. “I just want people to go and see it and to approach it with an open mind, and to engage bravely, empathetically, and boldly with it. I know that some people will say, ‘I don’t like history exhibits’, or maybe they’ll say, ‘I don’t know, I really love UW. Is this exhibit really for me? Am I gonna agree with the viewpoints expressed here?’ Everybody’s going to come with their own preconceived notions about the project and about the exhibit. I just want people to come and see. I think if you come and you see the exhibit, what you’ll see is that it’s a different history about UW, but it’s a vitally important and necessary history about UW. I think that people will find stories that are upsetting, disturbing, and disheartening. However, for every one of those, they’ll find hope, joy, and community. We really tried to strike that balance in the exhibit.”

The potential for what can come of the Public History Project is endless, but only achievable through the efforts of people who are willing to immerse themselves in learning something new, even if it may be difficult. As for those who have their own stories and experiences to tell, Lucchini Butcher was hopeful that the exhibit will inspire and drive people to make their voices heard.

“We anticipate lots of people coming forward to give us oral history interviews,” Lucchini Butcher said. “People who are able to come to the exhibit and say, ‘Hey, wait a minute, I was there. I’ll tell you a story.’ To which I’ll say ‘Please do.’ We’re going to be prepared and ready for that. We’ve already gotten emails from folks who say, ‘Did you know about this story?’ I’m like, ‘No, I didn’t. We didn’t find that.’ We want to keep being an avenue to note those things, and to encourage more research because there is a lot more research about the university that needs to be done.”

The hope of continued research and work to uncover these histories is present and tangible throughout the exhibit’s content and through the passion put on display by the research team who put it together. While more work is surely going to be necessary, the Public History Project will provide a great starting point for those wishing to listen and learn, and provide those who are all too familiar with the history an emboldened voice to share their story.

The exhibit will remain on display until December 23. More information about the Public History Project is available on the project’s website section through the University of Wisconsin-Madison here.