Special promotional content provided by Forward Theater Company.

By Khalid Y. Long, PhD

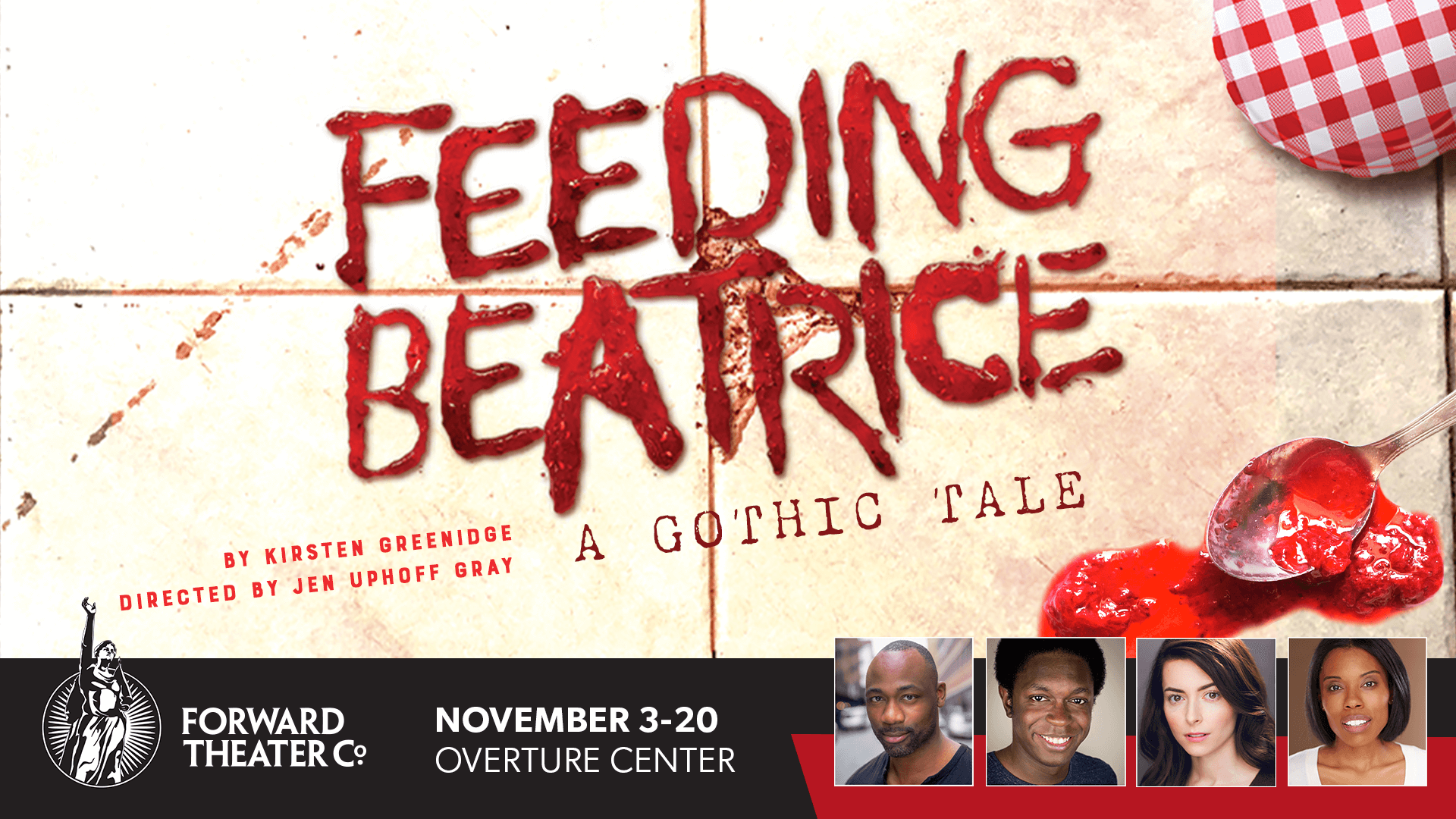

When Jen Uphoff Gray first contacted me about Kirsten Greenidge’s Feeding Beatrice: A Gothic Tale, she described the play with the following phrase: “this play is A Raisin in the Sun meets Beloved meets Get Out.” Intrigued, I read the play and instantly agreed. And then I shared that I would add Amiri Baraka’s 1964 Obie Award-winning play Dutchman to the mix, mainly because the plays equally examine the Black-white race relations through a sensual – and sexual – lens.

So, what do all these great pieces of American literature and cinema have in common? For starters, they each comment on the social fabric of American society. Even more, they collectively serve as a genealogical roadmap offering a glimpse into various periods of American history with a keen focus on topics such as American slavery, the dynamics of American race relations, the American dream, home ownership, and America’s fascination with the idea of the nuclear family.

Feeding Beatrice is a ghost story. The play centers on June and Lurie, an African American couple climbing the ladder toward the American dream, especially home ownership. Their dream becomes a nightmare when they meet Beatrice, a young, white ghost from the 1950s whose family once occupied the house that June and Lurie recently purchased. Friendly at first, Beatrice later reveals herself as an evil spirit that, by no mistake on Greenidge’s part, is tantamount to the evils of American history that haunt us today.

Feeding Beatrice is closely akin to Jordan Peele’s 2017 film Get Out, for they both use the genres of American gothic and horror to explore the above-mentioned topics. It should be noted, however, that Greenidge began writing Feeding Beatrice in 1999, almost twenty years before Get Out premiered. Nonetheless, the works are interrelated for each articulate thematic tropes associated with American gothic and, even more so, with Horror Noire.

The credit for introducing the term “Horror Noire” goes to scholar Robin R. Means Coleman, who, in her book Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present (2011), identifies it as a “double entendre,” for it “simultaneously hails the “dark,” or the “noire,” while also offering a nod to horror’s complex relationship with good and evil, right and wrong.” Even more, “Horror Noire” leans toward the “particular discursive power in the treatment of Blackness.” That is, “Horror Noire” racializes the genre of horror, thus modifying the genre to “have an added narrative focus calls attention to racial identity, in this case, Blackness—Black culture, history, ideologies, experiences, politics, language, humor, aesthetics, style, music, and the like.”

It is not ironic, then, that when Greenidge was asked to describe her play in five words, she stated, “Visceral, Clawing, Searing, Bitter and Historical.” As such, Feeding Beatrice is an American story that captures issues that have haunted Black Americans for centuries. And while those issues may be of little import for some, for many Black Americans, the notion of the American dream – and all that falls under its rubrics such as homeownership and parenthood – has continually resurfaced the horrors of American slavery, racism, and class.

To be sure, the play did not emerge from just anywhere. Does any art ever really emerge from just anywhere? The most direct influence on Feeding Beatrice is Margo Bennett’s story, No Bath for the Browns (1945), to which Greenidge was introduced by Alfred Hitchcock’s collection of short stories, Not for the Nervous (1965). Greenidge explains: “The basic idea is that there is a couple that buys a house; they can’t afford it. They agree they will eat bread and margarine for as long as it takes to pay off the house. They find a body in the bathroom underneath the floor, and they decide to just cover it up and not tell anyone. As you do. So, I thought that was interesting. I was intrigued by the pact, and I decided to marry all those ideas together.” In discussion with director Uphoff Gray and myself, Greenidge also confirmed that Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved (1987), which was adapted into a film in 1998, was indeed an influence on the play. Greenidge also shared that her introduction to dramatic literature was through Lorraine Hansberry’s award-winning play A Raisin the Sun (1959), so the impact of Raisin is prevalent within her larger body of work. And, with Feeding Beatrice, Greenidge joins the lineage of writers – in this case, Black women writers – who employ some manifestation of ghosts to ponder the weight of the past on the present. For Hansberry, it is the ghostly presence of Big Walter; for Morrison, it is the titular character of her novel, Beloved.

Greenidge, too, employs the ghost as both a spiritual being from the past and as a metaphor to examine the social fabric of American society. Thus, as Greenidge states, we “keep telling the same stories over and over again… because history keeps repeating itself. Over and over again. We’re all going to keep writing stories until we can all be free. It sounds cheesy, but more stories are going to be added to the pot; there are always going to be more. Because we haven’t figured it out yet.”

Feeding Beatrice runs November 3-20 at Overture Center for the Arts. Tickets are available here.

Dr. Khalid Y. Long is a scholar, dramaturg, and director specializing in African American/Black diasporic theatre, performance, and literature through the lenses of Black feminist/womanist thought, queer studies, and performance studies at the University of Georgia.