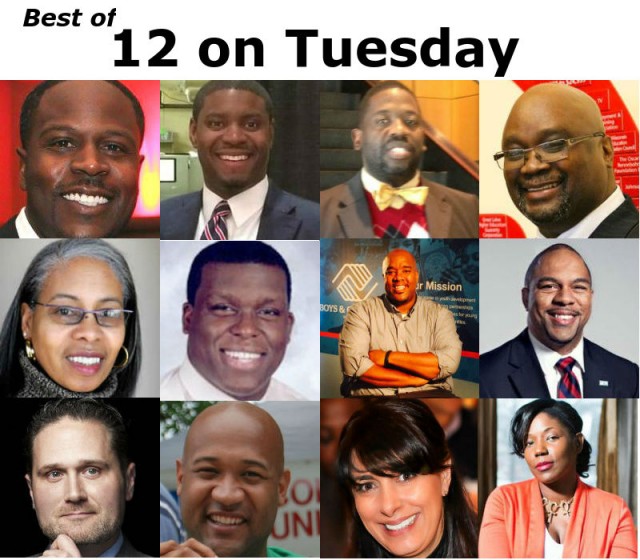

12 on Tuesday is taking a holiday break, so we’re looking back at the first few months of interviews with the leaders and personalities from Greater Madison and its communities of color. Today we’re looking to the future and what Madison needs to do to get past our racial disparities, as we ask:

What’s the biggest stumbling block to turning the corner on racial disparities?

Percy Brown, Jr: We acknowledge, examine and deal with race with the wrong lens. We often view race based on someone’s skin color but in truth, the origins of race was based on faulty European science that ranked human beings based on skin color as well as other physical characteristics (Great Chain of Being) and America used it to create a disguised economic caste system that was designed and implemented with a white supremacist framework that kept blacks enslaved for over 250 years. And much hasn’t changed 150 years post slavery. This is the truth of our history as a nation and America continues to mask this caste system by bombarding propaganda on the American psyche to make us all believe, even black people, that blacks have dysfunctional families, lack work ethic, are less than and are no more than criminals or thugs. Yes, these things are taking place in the black community but in my opinion, these are ongoing symptoms of internalized oppression, which comes from centuries of living in a racist society. The truth will set us all free and in order for us to eliminate racial disparities, this community must be progressive, forward thinking in truth about race and do what is required to transform our community into one that is inclusive and provides authentic pathways to social and economic prosperity for all. It’s ugly, painful and will require difficult days ahead if we choose to go this path, but is necessary and as Frederick Douglass once said, “without struggle, there is no progress.”

Rev. Everett Mitchell: The lack of transparent and intimate intersectional relationships. While the intentions and passions are genuine, we are still suffering from a lack of intersections that allow us to listen deeper.

Rev. David Hart: Black people, I love us, but many of us labor under the impression that there is no problem, no racial disparities to alleviate. If we don’t understand that we are slaves, we cannot be freed. What’s more, there are a small number of us who make a hefty living convincing white people in power that the Black community needs the kind of help only they can provide.

Dr. Ruben Anthony: Getting beyond talking, getting beyond the sensational news stories, getting beyond spectating and getting to action. This community has to make the investment necessary to make Madison the best community for all. It is to the advantage of the entire community. Improving the quality of life for those who suffer from disparities improves the quality of life of the Greater Madison community.

Gloria Ladson-Billings: First and foremost, recognizing the problem actually exists. I think the Race to Equity report came as a surprise to the majority community but Black people already knew the situation. The second issue is that this is a “process” community, and even if nothing gets accomplished people will accept that as okay because the “process was honored!” In other words, we tend to talk things to death.

Jeff Mack: My opinion is twofold – family structure/education and teacher representation. I came from a dual parent household where both parents had a college education and owned their own home. So the standard was set. To me, when I think of a “standard,” while it sets a precedence, it is the lowest level you can obtain to “pass” so-to-speak. I also came from a sports background, which pushes you to win, and be better than the rest. So in order to excel, I had to somehow do more, so it was ingrained in me that to be “standard” wasn’t acceptable. That pushed me to achieve more, or figure out how to “beat” the standard… (Still working on that…). As far as the teacher representation goes, from K-8th grade, I had 7 black teachers. At the time, I didn’t realize the impact of this, but in hindsight I think it had an enormous impact. So from a visual learning perspective (which I feel is the number one way in which children learn at that time in their lives) to see someone that looks like me and be the governing body of that environment, it gave me a feeling of an equal playing field, or the illusion, albeit true or not, that everyone is treated the same and held to a higher “standard” in class, just as I assumed I was.

Michael Johnson: There have been many announced initiatives that have made headlines with little to no financial support compared to the problems that exist. These kinds of announcements and initiatives give our community false hope, but make good headlines. Our community need a systematic management plan that is fully resourced with a leader(s) who are politically savvy. A team that has vision and can move a bold agenda forward. Until we add these components to the equation we will continue to stumble, fall and trip over these issues.

Maurice Cheeks: Silos. I have no doubt that there is a great deal of support for the idea of closing the disparities gaps throughout our community. There are a tremendous number of organizations making various efforts to be a part of the solution to helping Madison live up to our values. The greatest hurdle to meaningful change is simply getting agreement on a few areas to focus on, and then keeping track of who is accountable for doing what. If the university, the city, the county, the schools, the private sector, the non-profits, and the faith community were able to break down silos, share data, and establish a few measurable goals to be publicly accountable for… it would only be a matter of time before the rest of the nation was looking to learn from Madison as the national leader for closing the opportunity gap. This is how we are going to create a city where everyone feels welcome and able to thrive.

Zach Brandon: The lack of entrepreneurship. We must hire, compensate, mentor, promote, encourage entrepreneurship in, become customers of, and then ultimately work for people of color.

Mike Martez Johnson: The way we talk about them; As Ta-Nehisi Coates stated in Madison during his recent lecture, “Racism is not a disease of the heart, but the pocketbook.” Our race conversations are leaned in the direction of the individual and the personal, which has a place in conversations about humanity and acknowledging one’s humanity. What is missing is an economic component that looks closely at how our public and private institutions operate at the expense of communities of color. The lack of affordable housing in Madison’s communities of color, for example, can’t be easily explained as the mere outcome of racism, but as an intentional refusal to use local resources in poor black neighborhoods because they are poor.

Shiva Bidar-Sielaff: Change. We have made much progress over the past couple of years in acknowledging that we are a city with huge disparities. However, there is still a clear tendency of blaming others instead of internalizing each individual’s role and each institution’s role. Turning the corner requires changing major structures and institutions and shifting power dynamics — and when there is a push to change power dynamics there is resistance.

Brandi Grayson: People who have been in positions of power for decades and are not willing to admit that they got something wrong. So they keep doing the same thing over and over again expecting different results. Some folks even hold positions in Equity and Inclusion, and they identify themselves as being culturally competent, but are unaware of their own biases that lead to policies, practices and changes that negatively and disproportionately impact black people in Madison. Folks who have created policies that have led and/or contributed to racial disparities are unable to say, “this isn’t working.” Instead, they give excuses and ask for more money.

As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “ I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in this stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen Councilor or the KKK, but the white liberal, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice.”

Think about it. We have more than 4,400 nonprofit organizations in Madison. Yet, Madison is the worst place in America for me to live? How is it that we have so many do-gooders, yet disparity rates continue to climb? How is it that so many organizations and systems have missions that are rooted in equity and social justice, but they don’t have any black employees? If they do, those black employees are workers; they’re not part of the executive team, the decision makers. And moreover, how is it that an organization whose mission is to end homelessness and close the education gap, or a community center that serves black children, is controlled by an all-white board of directors?

How can they see and/or articulate black folk’s experiences? They can’t, but they do.

Am I saying no nonprofit in Madison is serving its clients? No, that is not what I’m saying.

Am I saying that an all-white board of directors are more likely than a diverse board to enact policies that impact black people negatively? Yes.

I am saying that in Madison, with all of our desires and intent to do right by those who are most impacted, we rarely take the time to look at things through the lens of impact — from the perspective of those we serve, or are supposed to serve. However, what we do well is gain support for programs and initiatives by marketing them to those who are funding them. We aren’t as good at creating programs and initiatives that empower people and build people.

Funders need to be able to measure outcomes. Based on my experience, empowerment, confidence and mental shifts are deemed unmeasurable.

However, in order for our people to get out of the system, we must first remove the system from within them. That doesn’t align with funders’ needs, and thus change doesn’t happen. Folks are recycled from one program to another, while organizations reward each other and honor each other for their work–but fail to ask clients if the programs are actually working.

The issue in Madison is that people think because they support the plight of Black people, or because they’re married to a black person, or because they have a black child or they’ve worked with “this” population for decades they are capable and educated enough to speak on the behalf of black people. And they do. And they fail miserably and they end up contributing to Madison being the worst place in the country for me to live.

In addition, systems that “serve the poor” are rooted in competition. For example the Tenant Resource Center lost $90,000 in the county budget. The $90,000 was given to Community Action Coalition. How is it that two of the biggest resource providers for poor families have to compete for funding? But we can add funding to the County’s Budget to fund political fluff, like a new department of Equity and Inclusion in Dane County. Huh? So, let’s fund more things that don’t work and underfund things that do?

The problem in Madison is folks are too busy pretending to be pioneers for change that they don’t have time to actually be it. Maybe the racial disparities are due to politics and allegiances, or maybe it’s due to folks doing the same thing over and over again, and each time expecting a different result. While saying, “we’re doing everything we can do to tackle this problem,” they’re actually doing everything they think they should do, rather than what communities of color are saying they need. Give the community control over the police, free the 350, invest in black-led initiatives and programming — and start listening. Listening and taking action would change the entire of fabric of Madison. Maybe that’s why folks are scared to change.