Dr. Rev. Carmen Porco, the longtime executive director of Housing Ministries of Wisconsin who has been a highly respected anti-poverty activist and a well-known advocate of low-income housing, officially announced his retirement in June following over a half-century of work, including developing the revolutionary Wisconsin Anti-Poverty Model to lift people out of poverty and to transform their lives.

“It’s difficult because I’ve retired from the organization where I don’t have the everyday responsibility,” Porco tells Madison365, “but I’m going to continue to try to promote some public policy debate and keep trying to get the attention of our elected officials to say, ’Look, you’ve wasted trillions of dollars under the guise of providing housing and other services for the poor … but it’s not effective.’

“And it’s not effective because your system of delivery is deficient. It’s not holistic in terms of bringing other entities — health, education, employment — into the picture of shelter,” he continues. “And it’s also deficient because you have never developed a positive psychology about the contribution that poor people make to our society in numerous ways.”

On top of being the CEO of Housing Ministries of American Baptists in Wisconsin since 2009, Porco has also been the founder and executive director of Northport and Packers Centers, Greentree-Teutonia Community Learning Center, and Plymouth Community Learning Centers since 1994.

Many of Porco’s initiatives, like the aforementioned Wisconsin Anti-Poverty Model, have lifted residents out of financial hardship and increased the grade point averages of school-aged children while reducing teen pregnancy and problem behavior. The model also secured funding for higher education scholarships and has diminished crime rates.

“One of the things I’ve felt from the very beginning is that if I’m going to do anything in housing, I’m going to turn it upside down,” Porco says. “Turning it upside down meant it had to be an integrative delivery system with all the components of human need. Also, I was going to hire the residents for the jobs because I wanted to show that hiring people who have the social and life experience of the problems we see in society are in a better position to really develop solutions.

“So after 30 years of putting it into place, building those learning centers, hiring the residents, providing training on leadership, management and organizational development, and allowing them to own the resource base and the responsibility for developing the identity of needs and solutions … 30 years now of experience says they’ve done a remarkable job,” Porco adds.

Dr. Charles “Chuck” Taylor, a longtime Madison educator and community leader, detailed a lot of this work in a book about Porco’s life titled “The Carmen Porco Story: Journey Toward Justice.”

Porco grew up Catholic in an impoverished steel mill town in West Virginia. His Italian parents started out as bootleggers before they opened up a barroom in Weirton, West Virginia where Porco spent his youth interacting with a variety of people from diverse backgrounds.

Porco credits his mother, Theresa, with instilling in him at a very early age the power of caring and love and giving back to the community he resides in.

“My mother, God bless her, I don’t know how she did it … she worked with my father, and mainly she was the brains behind it because my father was an immigrant and he couldn’t speak English well, he couldn’t write,” Porco remembers. “So my mother ran the restaurant, ran the bar room, took care of us kids, plus my brother Jojo, who had Down’s Syndrome, and lived at home with us.”

One day, Porco’s mom did an interesting and generous thing for the people in their steel mill town during some hard times that made Porco initially suspicious.

“I was about nine years old going on 10, and the steel mills started laying off a lot of people in town,” Porco remembers. “All of a sudden, these three Black ladies and my mother would get in the booth in the bar room, and they would be talking, and they had this accountant’s column pad book with all the columns and rows. And I was saying to myself, ‘What is going on?’”

“Finally, one day after the three ladies left, I said to my mom, ‘Why are you giving them money? I know they help us out sometimes when we’re really busy, but, you know, we haven’t been busy lately.’ She responded, ‘That’s the point.’ My mom gave the ladies money for the families for what they needed.”

Porco told his mom, “They’ll never pay you back!”

“And she looked at me with amazement and she said, ‘Babe, you don’t give money to help people to expect it paid back. Let me teach you something. When the people are working, they come and buy food here, and they drink here. They spend their money here and that puts food on our table, that gives us money to continue the business and put clothes on your back. These people are my market. Now, if they’re hurt, we have some money enough to help each of them out during this period. What I’m doing is protecting my market. You ought to learn that because what goes around comes around.’

“You need to realize that people become an extension of you in whatever you’re doing with them, and you got to follow the end result of that extension and make sure you’re paying it back,” Porco says his mom added.

In a sense, Porco says, he was witnessing the first community center.

“Yeah, it was a bar and it was a restaurant, but it was a community thing, and the people did respond. Now, when my mother passed away, there were a number of people that came up and said, ‘Miss Daisy gave me this. I want to pay it back.’ So the people had integrity,” Porco remembers. “They were poor people. They spoke very directly. It showed me something about the honor and integrity of people, and that’s why I developed the belief that we’re all brothers and sisters, and that is the common base we need to start from and go back to, and repeatedly remind ourselves: are we whole with that base? So my mother taught me that. She was an amazing woman.”

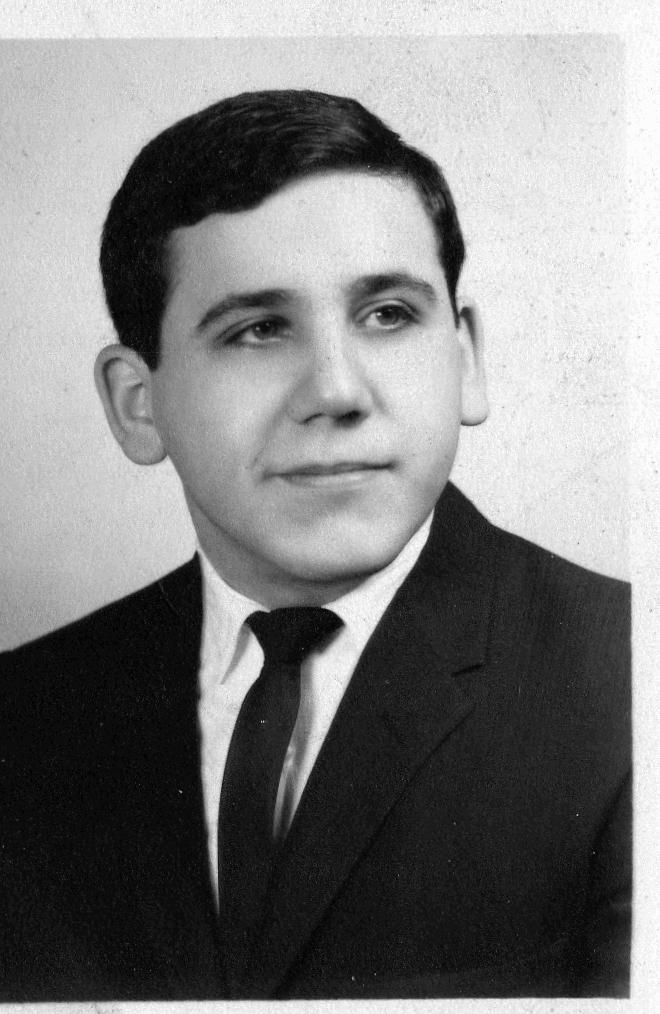

An internship where he worked at the Milwaukee Christian Center in Milwaukee in 1965 is where Porco first met the famous Catholic priest, Father James Groppi.

“At age 18, I was on an internship from the American Baptist Omission Society to study the civil riots going on in the country and was stationed in Milwaukee to study Father Groppi and marches and the open housing that he worked for,” Porco remembers.

“It was interesting because I had not been used to a priest being one who spoke out on social issues. Back home, our priests were quiet, parish people who didn’t make any waves,” Porco adds. “Now you have a Catholic priest that was shaking the city up and had the audacity to organize a Black Party of men that were the commandos and to then have the church put at risk by being a spokesperson for the poor against the mighty system.”

Father Groppi was a beloved civil rights activist who became well known for leading numerous protests, many times where he would be arrested. Groppi’s mission of seeking fairness and equality in housing influenced how Porco approached his role in developing and leading Housing Ministries of Wisconsin

“I found Father Groppi to be an interesting character, and as I got to talk with him more, it caused me to really examine this concept of Jesus Christ,” Porco says. “Now, I was studying it through a minister back home who got me off the streets and out of trouble. But I was studying it as a fundamental. As I was watching Father Groppi, I would see him practice it … it would be what would be called non-judgmental witness. Now that was different than unconditional love, which he also practiced, but non-judgmental witness was similar to Martin Luther King’s non-violent direct action that he picked up from Gandhi.”

Under Father Groppi, Porco learned about the importance of extending grace to people and about what he would call the “covenant of community.”

“Ultimately, the principle of Jesus is saying, ‘I’m communal. I’m in community. I’m of community, and I am community.’ And so I wrote a sermon on that, and preached it, and I was critical of the church,” Porco remembers. “We’re always giving imagery and symbols, but not the substance of the principles as to what constitutes Jesus. So that’s what Father Groppi taught me.”

Rev. Porco has a Doctor of Divinity, honoris causa, from Central Baptist Theological School; a Master of Divinity from Andover-Newton Theological School; a bachelor of science in social psychology from Alderson Broaddus College; and was part of the Executive Education Program at Harvard University, a joint program of the institution’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and School of Business.

Recently at Centro Hispano’s new Calli Building, Porco was honored with the Ilda Conteris Thomas Award, named after Centro Hispano of Dane County’s founder. This award represents someone who, with humility and values aligned with Centro’s mission, ensures a strong Latinx voice.

The award is now added to several of the wonderful honors and awards Porco has obtained throughout his career including the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award from the City of Madison and Dane County and a Badger Bioneer from Sustain Dane. He was presented with the “Educator of the Year” award by the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and the Champion of Change Award from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. There are also honors in Porco’s name: “The Carmen Porco Chair” in the Center of Business and Poverty at Oxford University’s Said School of Business, held by Professor John Hoffmire, and the “Carmen Porco Justice Award” by the Wisconsin Council of Churches.

“The Champion of Change Award in 2005 from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development is an award that really stood out to me,” Porco remembers. “They recognized under that administration that this model I developed has got a lot of worth to it, and it also allowed me to speak throughout the country pushing the community learning centers on low-income housing.

“The other award that I’m most proud of that I was honored with toward the later part of my career that focuses more on education was the one that was the chair in The Center on Business and Poverty, that’s housed in Oxford University [in England],” Porco adds. “My wife and I went over to Oxford and had the grand opportunity to receive the plaque in the Rose Hall. So that meant a lot to me. I was very proud of that award.”

On top of everything else, Porco has been the president of Porco Consulting since 1980. Since 1981, he has been the executive director of HUD Housing for American Baptist Homes of the Midwest. During retirement, Porco still has many ambitions including writing a book.

“There is some gardening and landscaping I would like to do, but I will also to write a book,” Porco says. “I want to keep my focus on public policies and how I might be able to influence and help make some improvements, and then smoke my pipe and work on writing the book. I’m hoping to have the book done in a year and a half at the latest.”

Porco says that he always believed that if you treat people with dignity and believe in them they would achieve accordingly.

“What I’ve come to learn is that too many people dash the hopes of young people, because young people might have a very idealistic sense, but dreams are made by the pieces of idealism coming together, and one should never discourage them,” Porco says.

“I tell young people that how you perceive affects how and what you achieve, so don’t give up your perceptions. Go for it. There’s going to be struggles, but go for it,” Porco continues. “I think it’s important to help people to come to this true sense of what they believe they want to be and do, and then encourage them. I also let young people know: don’t think there’s not going to be some pain and suffering. If there’s no pain and suffering, it means you haven’t moved very far.”

Most importantly, Porco wants younger people to know that if you want true happiness, making money is not the key – it’s finding what you truly feel good about doing and doing it with a passion.

“And don’t let anybody make you think that you can’t do it,” he says.

What does Porco hope that people remember about him and his long, illustrious career?

“I would hope that they would say that I always took the time for them and I always encouraged them and never made them feel lesser,” Porco says. “I would hope some of them will remember that I always said,’ Look, you’re the most powerful person in the world. You just don’t know it yet.’

“So I would hope they would remember that I always try to get them to think of that inner core being of theirs and the beauty of it and the strength of it, and that it’s a gift there to give to others, not by proselytizing, but by putting word and deed together with honor and integrity.”