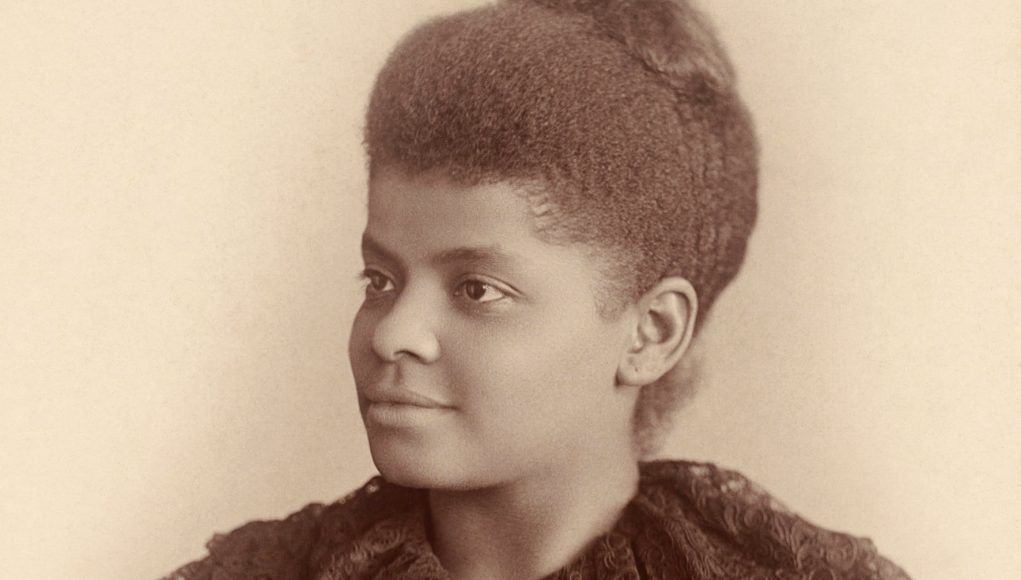

In 1892, journalist and former teacher Ida B. Wells reported on the lynching of three of her friends — Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart — who were lynched for the “crime” of opening a grocery store called “People’s Grocery” in Memphis, Tennessee, that “took” customers from competing white businesses. The white store owners went to attack People’s Grocery and in the ensuing scuffle the black men attempted to defend themselves and their property and shot one of the attackers. All three men were arrested but a mob broke into the jail and brutally lynched them. In her journalist description of conditions for black people in Memphis, Wells urged Black people to move because of the city’s refusal to protect black lives and property. Wells was telling us almost 125 years ago that “Black Lives Matter!”

From the point of her first missive in “The Free Speech,” Wells and others in the black community began documenting the brutality of lynching that plagued their community. In 1916, the NAACP established an “Anti-Lynching” Committee to develop legislative and public awareness campaigns. In 1919, the Committee published, “Thirty years of lynching in the United States, 1889-1918.” This report indicated that 3,224 people were lynched in the 30-year period. Of these, 702 were white and 2,522 black. This is an average of 84 black people a year! Among the justifications given for the lynchings were petty offenses such as “using offensive language, refusal to give up land, illicit distilling.”

“This ‘rash’ of shootings of unarmed black people we see on the nightly news and on our social media feeds are not new. Ida B. Wells told us more than a century ago that although many whites do not believe it, ‘Black Lives Matter!'”

The differences between what Wells and the NAACP reported back then compared to what we are now experiencing are that they lacked the instantaneous communication of Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and cable news to let the world know what had happened to black people and the lynchings were allegedly carried out by extra police or law enforcement individuals. However, we know that a close relationship existed between sheriffs, deputies, and police officers and organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, White Citizen Councils, and vigilante groups that carried out these heinous acts.

The point I am making is that killing black people at will has been a way of life for some segments of law enforcement. And, claims of “implicit bias” have become the latest and most convenient cop-out. While I do not deny Eberhart’s theoretical construct, I do not believe we should use it to give trained, professionals a pass on killing black people. I walk into university classrooms all the time and truth be told I have “implicit bias” toward white students. My implicit bias comes from more than 30 years of working with them and more than a few unpleasant interactions based on our racial differences. However, I have disciplined myself not to allow my biases to interfere with giving each INDIVIDUAL a fair chance to counter any biases I might have. I am still uncomfortable walking into a sporting event filled with drunk and rowdy white males. I am still uncomfortable when recognizing that my career fate may lie in the hands of white professionals. But, nothing in those “implicit biases” forces me to pack a weapon and shoot them when I feel threatened. I cannot let my “implicit biases” overrule my judgment.

This “rash” of shootings of unarmed black people we see on the nightly news and on our social media feeds are not new. Ida B. Wells told us more than a century ago that although many whites do not believe it, “Black Lives Matter!”