By Edgar Mendez and Devin Blake,

Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service

In many ways, Hamid Abd-Al-Jabbar’s life story involved redemption. A victim of abuse who was exposed to alcohol and drugs while growing up on Milwaukee’s North Side, he made dangerous choices as a teenager. By age 19, he landed in prison after shooting and killing a man during a 1988 drug house robbery.

But he worked on himself while incarcerated, his wife Desilynn Smith recalled. After he walked out of prison for good, he found a calling as a peace activist. He became a violence interrupter for Milwaukee’s 414 Life program, aiming to prevent gun violence through de-escalation and intervention.

Abd-Al-Jabbar may have looked healed on the outside, but he never moved past the trauma that shaped much of his life, Smith said. He wouldn’t ask for help.

That’s why Smith still grieves. Her husband died in February 2021 after ingesting a drug mixture that included fentanyl and cocaine. He was 51.

Smith now wears his fingerprint on a charm bracelet as a physical reminder of the man she knew and loved for most of her life.

“He never learned how to cope with things in a healthy way,” said Smith, executive director of Uniting Garden Homes, Inc., an organization that provides mental health and substance use services on Milwaukee’s North Side. “In our communities addiction is frowned upon, so people don’t get the help they need.”

Abd-Al-Jabbar is part of a generation of Milwaukee’s older Black men who are disproportionately dying from drug poisonings and overdoses, even as the opioid epidemic slows for others.

Milwaukee County is among dozens of U.S. counties where drugs are disproportionately killing a generation of Black men, born between 1951 and 1970, an analysis by The Baltimore Banner, The New York Times and Stanford University’s Big Local News found. Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service and Wisconsin Watch are collaborating with them and eight other newsrooms to examine this pattern.

Times and Banner reporters initially identified the pattern in Baltimore. They later found the same effect in dozens of counties nationwide.

In Milwaukee, Black men of the generation accounted for 12.5% of all drug deaths between 2018 and 2022. That’s despite making up just 2.3% of the total population.

The county’s older Black men were lost to drugs at rates 14.2 times higher than all people nationally and 5.5 times higher than all other Milwaukee County residents.

Six other Wisconsin counties — Brown, Dane, Kenosha, Racine, Rock and Waukesha — ranked among the top 408 nationally in drug deaths during the years analyzed. But Milwaukee was the only one in Wisconsin where this generation of Black men died at such staggering rates.

Milwaukee trend accelerates

The trend in Milwaukee County has only accelerated since 2022, the last year of the Times and Banner analysis, even as the county’s total drug deaths decline, Milwaukee NNS and Wisconsin Watch found.

Drugs killed 74 of the county’s older Black men in 2024. The group made up 17.3% of all drug deaths — up from 16.2% in 2023 and 14.1% the previous year, medical examiner data shows.

Abd-Al-Jabbar’s story shares similarities with many of those men. Most used cocaine that was cut with stronger fentanyl — the faster-acting drug has fueled the national opioid epidemic. Most had a history of incarceration.

They lived in a state that imprisons Black men at one of the country’s highest rates. Wisconsin is also home to some of the country’s widest disparities in education, public health, housing and income. Milwaukee, its biggest city, helps drive those trends.

Marc Levine, a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee researcher, concluded in 2020 that “Black Milwaukee is generally worse off today than it was 40 or 50 years ago” when considering dozens of quality of life indicators.

Meanwhile, limited options and lingering stigma prevent a generation of Black men from accessing drug treatment, local experts told Milwaukee NNS and Wisconsin Watch.

“Black men experience higher rates of community violence, are often untreated for mental health issues and experience greater levels of systemic racism than other groups,” said Lia Knox, a Milwaukee mental wellness consultant. “These all elevate their risk of incarceration, addiction and also death.”

A network of organizations providing comprehensive treatment offers hope, but these resources fall far short of meeting community needs.

A silent struggle

Smith and Abd-Al-Jabbar first started dating at 14, and they had a child together at 16. But as their relationship blossomed, Smith said, Abd-Al-Jabbar silently struggled with what she suspects was an undiagnosed mental health illness linked to childhood trauma.

“A lot of the bad behaviors he had were learned behaviors,” Smith said.

Abd-Al-Jabbar became suicidal as a teen and began robbing drug dealers.

When he entered prison, Abd-Al-Jabbar read and wrote at a fifth grade level and coped like a 10-year-old, Smith said. By age 21, she said, he’d already spent two years in solitary confinement. But he had the resolve to change. He began to read voraciously and converted to Islam.

He was released from prison after 11 years, but returned multiple times before leaving for good in 2018. Smith and Abd-Al-Jabbar married, and he started earning praise for preventing bloodshed as a violence interrupter.

Still, he struggled under the pressures of his new calling. The work added weight to the trauma he carried into and out of prison. His mental health only worsened, Smith said, and he turned back to drugs as a coping mechanism.

“The main thing he learned in prison was how to survive,” she said.

Most men lost were formerly incarcerated

At least half of Milwaukee’s older Black men lost to drugs in 2024 served time in state prison, Milwaukee NNS and Wisconsin Watch found by cross-referencing Department of Corrections and medical examiner records. More than a dozen other men on that list interacted with the criminal justice system in some way. Some served time in jail. For others, full records weren’t available.

Most of the men left prison decades or years before they died. But three died within about a year of their release. A 55-year-old North Side man died just 22 days after release.

National studies have found high rates of substance use disorders among people who are incarcerated but low rates of treatment. Jails and prisons often fail to meet the demands for such services.

In Wisconsin, DOC officials and prisoners say drugs are routinely entering prisons, putting prisoners and staff at risk and increasing challenges for people facing addiction.

Thousands wait for treatment in prison

The DOC as of last December enrolled 815 people in substance abuse treatment programs, but its waitlist for such services was far higher: more than 11,700.

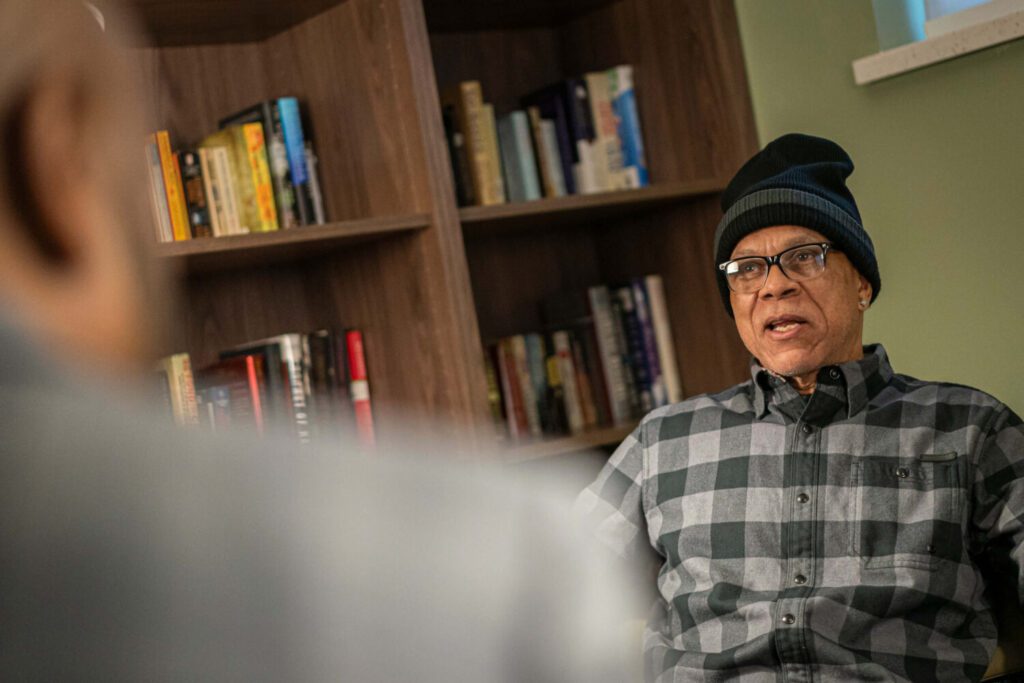

“You don’t really get the treatment you need in prison,” said Randy Mack, a 66-year-old Black man who served time in Wisconsin’s Columbia, Fox Lake, Green Bay and Kettle Moraine correctional institutions.

Leaving prison can be a particularly vulnerable time for relapse, Mack said. Some men manage to stop using drugs while incarcerated. They think they are safe, only to struggle when they leave.

“You get back out on the streets and you see the same people and fall into the same traps,” Mack said.

Knox, the wellness consultant, agrees. After being disconnected from their communities, many men, especially older ones, leave prison feeling isolated and unable to ask for help. They turn to drugs.

“Now with the opioids, they’re overdosing and dying more often,” she said.

For those who complete drug treatment in prison, the DOC offers a 12-month medicated-assisted treatment program to reduce the chances of drug overdoses. Those who qualify receive a first injection of the drug naltrexone shortly before their release from prison. They continue to receive monthly injections and therapy for a year.

Access to the program is uneven across the state. Corrections officials have sought to expand it using settlement money from national opioids litigation. In its latest two-year budget request the department set a goal for hiring more vendors to administer the program.

Democratic Gov. Tony Evers plans to release his full budget proposal next month. His past proposals have sought millions of dollars for treatment and other rehabilitation programs. The Republican-controlled Legislature has rejected or reduced funding in most cases.

Mack said he received some help while in prison, but it wasn’t intense enough to make a breakthrough. Now he’s getting more holistic treatment from Serenity Inns, a North Side recovery program for men.

Executive Director Kenneth Ginlack said the organization helps men through up to 20 hours of mental health and substance use treatment each week.

What’s key, Ginlack said, is that most of his staff, including himself, are in recovery.

“We understand them not just from a recovery standpoint, but we were able to go back to our own experiences and talk to them about that,” he said. “That’s how we build trust in the community.”

Fentanyl catches cocaine users unaware

Many of the older men dying were longtime users of stimulants, like crack cocaine, Ginlack said, adding they had “no idea that the stimulants are cut with fentanyl.”

They don’t feel the need to use test strips to check for fentanyl or carry Narcan to reverse the effects of opioid poisoning, he said.

Last year, 84% of older Black men killed by drugs had cocaine in their system, and 61% had fentanyl, Milwaukee NNS and Wisconsin Watch found. More than half ingested both drugs.

Months after relapsing, Alfred Carter, 61, decided he was ready to kick his cocaine habit.

When he showed up to a Milwaukee detox center in October, he was shocked to learn he had fentanyl in his system.

“What made it so bad is that I hear all the stories about people putting fentanyl in cocaine, but I said not my people,” Carter said. “It puts a healthy fear in my life, because at any time I can overdose — not even knowing that I’m taking it.”

Awareness is slowly increasing, Ginlack said, as more men in his program share stories about losing loved ones.

Milwaukee’s need outpaces resources

Expanding on its original outpatient treatment center on West Brown Street, Serenity Inns now also runs a residential treatment facility and a transitional living program and opened a drop-in clinic in January. Still, those don’t come close to meeting demands for its services.

“We’re the only treatment center in Milwaukee County that takes people without insurance, so a lot of other centers send people our way,” said Ginlack, who said the county typically runs about 200 beds short of meeting demand. “My biggest fear is someone calls for that bed and the next day they have a fatal overdose because one wasn’t available.”

‘I don’t want to lose hope’

Carter and Mack each intend to complete their programs soon. It’s Mack’s fourth time in treatment and his second stint at Serenity Inns. This time, he expects to succeed. He wants to move into Serenity Inns’ apartment building — continuing his recovery and working toward becoming a drug counselor.

“My thinking pattern has changed,” Mack said. “I’m going to use the tools we learned in treatment and avoid high-risk situations.”

Carter wants to restore his life to what it was before. He spent years as a carpenter before his life unraveled and he ended up in prison. He knows he can’t take that life back if he returns to drugs.

“I have to be able to say no and not get high. It doesn’t do me any good, and it could kill me,” he said. “I have to associate myself with being clean. I don’t want to lose hope.”

As Smith reflects on her partner’s life and death, she recognizes his journey taught her plenty, too.

“I was hit hard with the reality that I was too embarrassed to ask for help for my husband and best friend,” she said. “I shouldn’t have had that fear.”

Need help for yourself or a loved one?

You can find a comprehensive list of substance abuse treatment services by visiting our resource guide: Where to find substance use resources in Milwaukee.