Our Good Earth will be on display at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art in downtown Madison until August 21. An opening reception was held this past weekend. Our Good Earth addresses how modern and contemporary artists represented in the museum’s permanent collection have portrayed the natural world and imbued it with meaning. With both a celebratory and critical eye, the artists represented in the exhibition visualize nature in works of art that document a great range of locales, geological features, and weathers in equally diverse media and styles.

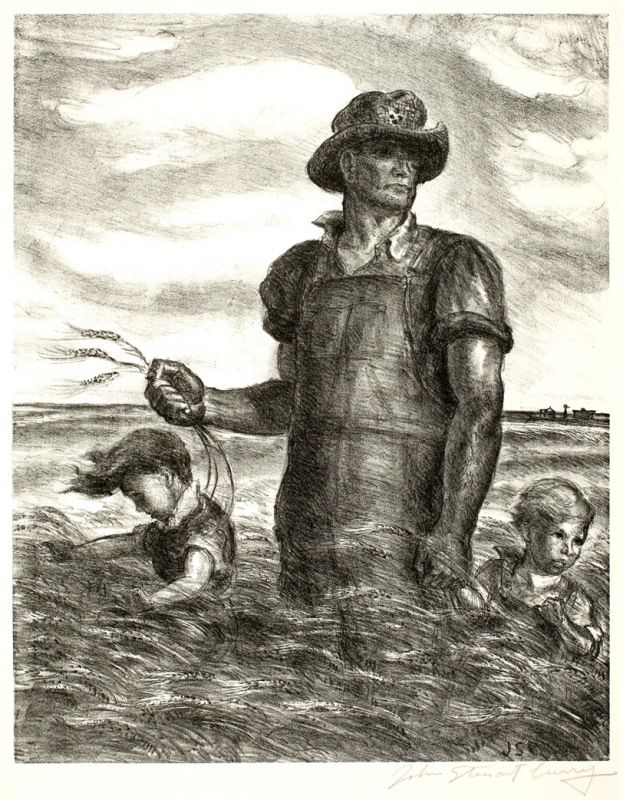

Our Good Earth takes its title from a 1942 lithograph by John Steuart Curry that depicts a farmer and his two young children standing waist high in a bountiful field of wheat. Curry’s implication of a nurturing and spiritualized earth rests upon a notion of nature expressed in early nineteenth-century Romantic landscape painting. The natural world—its diverse topography and flora and fauna—is an embodiment of divine grace. Nature in its purity, however, was understood by both Romantic artists and poets to be jeopardized by human intervention, most notably, the deleterious effects of the Industrial Revolution. The worsening of these consequences over the years has altered and, in some cases, irreparably damaged the natural landscape. In our time, fossil fuel emissions among other human-made toxins and actions have led to global warming, with the prospects of drastic climate change and threatened economies that endanger human populations, animal species, and the land as we know it.

Our Good Earth begins with two visual accounts of the planet’s beginnings: the Mayan creation myth as rendered by Carlos Mérida in a selection of lithographs from his Estampas del Popol Vuh (1943); and The First Four Days of Creation (1976), a series of wood engravings by Fritz Eichenberg that show the earth’s divine formation before God’s introduction of animals and humanity.

The exhibition then proceeds to works of art that take a traditional approach of visualizing nature in lyrical and poetic terms. Jack Beal’s Taylor’s Way (1962) with its glowing colors and Impressionist brushwork exemplifies this type of landscape art. What follows next are sections devoted various aspects of earth’s environment, including, among others: mountains (Marsden Hartley, Trees and Mountain, 1932), animals (Thomas Cornell, Turtle II, date unknown); water (Pat Steir, Long Vertical Falls #3, 191), snow (Lee Weiss, Winter Landscape, 1962); and fire (Charles Munch, Fire Signs, 1989).

As Our Good Earth continues, disasters and threats to the world (both natural and man-made) are visualized directly and indirectly as compromised to the sustainability of human and animal ecologies. France Myers responds to the horrific intensity of Hurricane Katrina in Medusa Deluged, 2006. Additionally, the Richard Misrach photograph of an empty and corroded swimming pool in an abandoned Californian resort town in Diving Board #8, Salton Sea (1987), the artificial lake of the earlier twentieth century is now dead of extreme salinity.

It may no longer be possible to view landscape art with an innocent eye. Our Good Earth, in its implied narrative of mourning, aims to stimulate audiences to think about social and political issues made urgent by a changing planet and what we stand to lose.