The city of Madison has a very large number of nonprofits per capita, many of which have been dedicated, for years and decades, to lessening racial disparities. Madison also still has some of the nation’s worst racial disparities.

That irony is not lost on Brandi Grayson.

“It doesn’t make sense to me. In progressive Madison, people say that they want to do the work, but they don’t want to be uncomfortable. And I know that I make them uncomfortable,” Grayson says. “But in order for us to get the work done, we have to get used to being uncomfortable. We have to move past funding things that maintain and uphold the status quo.

“We need to empower people to understand our own behaviors. White people can’t tell us why we behave the way we behave. You have no f*cking idea,” Grayson continues, laughing. “That you think that you can is the problem. In a lot of the organizations that is being done right now, through different efforts and movements, they don’t even talk about it – they don’t talk about racial socialization or structural racism. In the work of non-profits, you’re really not allowed to.

“The system,” she adds, “is created to sustain itself.”

Grayson knew that in Madison something completely different was urgently needed and with that in mind, she founded Urban Triage. It is the only organization in Madison that is providing psycho-education, trauma-informed care, advocacy, personal development skills, parenting skills, education, and analysis building for black people to stay engaged and present in the lives of black children while promoting healing and self-sufficiency.

“Our mission is to foster black families’ self-sufficiency, community leadership, advocacy, and student success through parent engagement and cultural heritage,” Grayson says.

Urban Triage aims to improve the well being — academically and mentally — of African-American students and students with disabilities through economic empowerment, restorative justice, community engagement and community leadership.

Grayson came up with her idea to start Urban Triage years ago, back when Young Gifted and Black (YGB) first started.

“I’ve been doing the work of Urban Triage without a support system for four years,” Grayson tells Madison365 in an interview on the patio of Barriques on South Park Street. “I’ve been advocating for parents and families in schools, in the criminal justice system, and for foster parents and for parents of children who are high-risk.”

It was all of the recent racial incidents that were happening at schools in Madison that made her decide to get back to it and to make it official.

“The incident with the 11-year-old [at Whitehorse Middle School in February] is what really kicked it off for me,” she says. “I started having community meetings and started talking to people and we decided we need to do something. How do we protect our students? How do we engage community members to be present and engaged in what’s happening in our school district? How do we equip people with tools to navigate the system. Where do we start?”

“We’re actually starting with the parents and empowering black people to be self-sufficient and to navigate systems. Nobody is talking about what structural racism really means. When we talk about structural racism, it’s the lack of access to things. But if we’re not teaching black people, or people who are most disenfranchised, to access and navigate those resources and have their own understanding and analysis of structural racism and how it impacts them, in my opinion, then we’re not talking about anything!”

Grayson knew that they needed to provide the proper education to the parents.

“But not the typical education. Racial socialization. Understanding the systems that we exist in. Understanding political, social, and economic systems,” Grayson says. “Understanding our history as it relates to trauma and the injury and the consequences and that it relates to trauma that we’ve endured and how that trauma impacts our ability to stay engaged and present for our children and how the trauma ends up being transferred and projected onto our children by us and by other systems.”

Grayson’s currently working on the paperwork to become a 501c3. It can be very hard to raise money as a non-profit; even harder for a non-profit like Urban Triage because so much of Madison sees Grayson as a radical.

“I’m not going to let these ideas of social constructs – what’s appropriate and not appropriate – to stop me from doing what I know in my heart and my soul is the work that needs to be done,” Grayson says. “All money ain’t good money. But I know the money will come.”

A GoFundMe page has been set up to build capacity to protect black children. It’s already more than a quarter of the way to its goal of $20,000. Grayson says that she is also working on grant proposals.

“I have a whole team working with me. I have 10 people who are part of our research crew. I have another five white people who solicit funds from their networks,” she says. “I have Sara Hinkley – who I call my chief of staff. She does all of the administrative work for me and with me. She’s like my think-tank where we can sometimes figure out how we need to maneuver. I work very closely with Sankofa.

“I have a very strong team. It’s mostly white people but I feel like that’s the work that white people should be doing,” Grayson adds. “They should be supporting the work and using their privilege and networks to help get the work done.”

Most importantly, Grayson says, Urban Triage is doing work that people in Madison just aren’t doing.

“We’re actually starting with the parents and empowering black people to be self-sufficient and to navigate systems,” Grayson says. “Nobody is talking about what structural racism really means. When we talk about structural racism, it’s the lack of access to things. But if we’re not teaching black people, or people who are most disenfranchised, to access and navigate those resources and have their own understanding and analysis of structural racism and how it impacts them, in my opinion, then we’re not talking about anything!

“The people who are most impacted have to have the skills to maneuver. The system doesn’t stop doing what it’s doing because we say we want to all kumbaya,” she continues. “People need tools and education and information. So we not only deal with the structural racism piece, but we also empower people’s self-sufficiency. ‘I can do this. I got this.’”

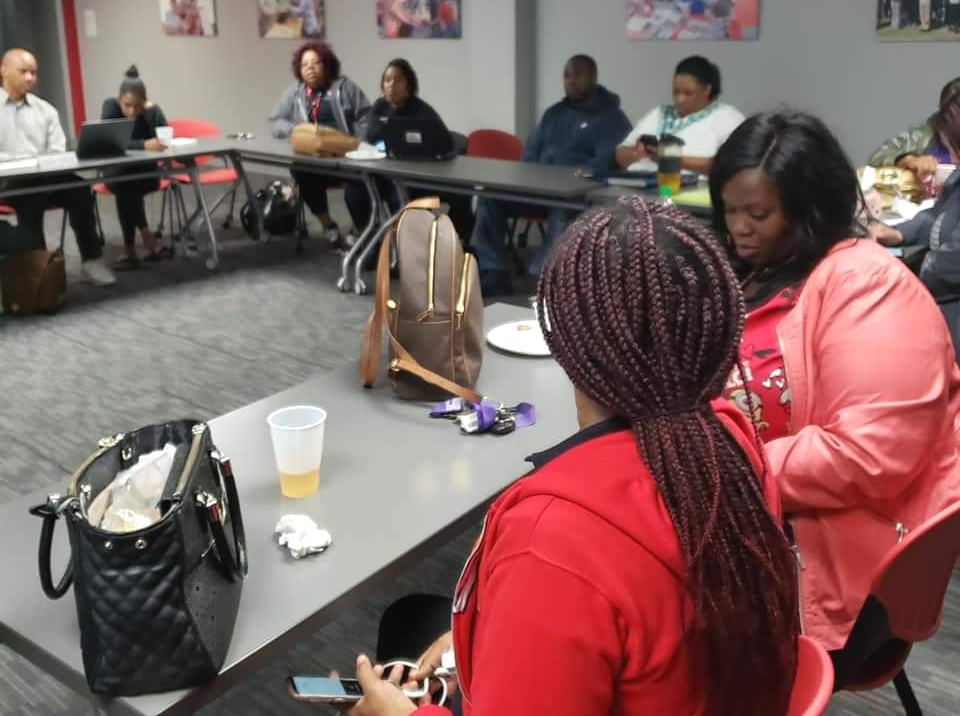

Urban Triage parent leadership/advocacy training has already begun, with 20 parents enrolled in the cohort learning about the different systems from a place of cultural relevancy. So far, many of the parents say they are enjoying it.

“Parent Leadership Training is providing me a space to learn (by definition) the nuances of how politics in our schools and government effect black children,” R.L. Jenkins tells Madison365. “Although the historical aspect is painful, I find solace in the spirit of reversing the outcomes for children of color in Wisconsin.”

“Being in this training has allowed me to advocate more for myself without becoming enraged!” Lolita Phillips tells Madison365. “Our training program has inspired me to build community between Teachers and Parents in oppose to getting angry and doing nothing to bring awareness to what needs to be talked about. My project will begin this summer and the plan is to start some asset building in our community!”

The impact has been immediate, Grayson says. “People are in the classes and the light bulbs are going off in their heads and they are connecting their own trauma with how they interact with their own kids. It’s amazing … people are feeling more confident and more empowered. And this has allowed parents to be more involved.

“What we know through empirical studies and evidenced-based models is that when parents, specifically black parents, don’t feel like they are heard, they don’t show up,” she adds. “When they don’t feel like they belong, they don’t show up. And that leaves our children out there alone fending for themselves. If we really want to engage our children and to address our achievement/educational gaps, we really have to include the family structure.”

It’s a 90-day training, during which parents do 12-15 hours per month and get paid $25 an hour. All of the funding is community-led and community-raised.

“We also have to empower people economically as it relates to community engagement,” Grayson says.

After the 90-day training, they will receive a certification and will interview to become part of the Rapid Response team where they will get additional training. The Rapid Response Team (RRT) is a strategic development and immersive training program that equips black parents and community members with the skills and tools required to advocate, be present, inspire and empower black children. All the while centering children who are LGBTQ and students with learning disabilities.

“The point of the Rapid Response Team is to respond to incidents of race and abuse within the Madison school district,” Grayson says. “Our website will allow people to report information and data. The data will get sent to this database that will alert our Rapid Response members who will respond accordingly so parents don’t have to navigate systems by themselves.”

Parents will also be able to find other community resources at the webpage to support them and their students.

“It’s for the black parents that are present and engaged in our MMSD to create a mechanism for us to be present in the school district. I had spoke to [MMSD Superintendent] Jennifer Cheatham about this prior to doing the training and she said, ‘Oh, this is wonderful.’ And we talked about how to get parents inside the schools instead of police. This is really about shifting from the idea that police are the answers and moving towards more parent-led, community-led presence in our schools – people who have interpersonal relationships with children.

“Culturally, black people have to have interpersonal relationships. If we don’t trust you … if we don’t feel like we’re genuine. If we feel like something is off, then you won’t get a welcoming response and it is reflected in our children,” Grayson continues. “Put people in the schools that know our children, can advocate for our children and can be a liaison for our children and really a translator between what our children are saying and what they need to the white staff and administrators.”

Much of the challenge in the school district is about language, Grayson says.

“I had this one incident where this teacher reported a kid she was helping. She was leaning over his shoulder and showing him the work and his response was, ‘Man, you tweakin’. I don’t get this.’ So she called the behavior response team and said that he had threatened her. But there was no threat,” Grayson says. “Now imagine if there was someone in that classroom who understood his language. And he responded differently, instead of responding in this negative way that escalated the situation and devalued him. And he still left without knowing what the f*ck was going on and got in trouble.

“What he was really saying was, ‘This is hard. I don’t get it. I need a different approach,’” Grayson adds, laughing. “That’s all he was saying. It’s crazy. The language barrier. But we don’t recognize black vernacular as a language. So then our children are in spaces where they are misunderstood and not heard which increases the probability of them responding in a not-so-appropriate way to staff.”

Grayson says that we need to put community members in our schools to be translators, advocates, and liaisons and support not just for the students, but for the teachers and the staff.

“Black language is an important part of all this and it empowers our communities to be self-sufficient and to do the work ourselves and it transfers responsibility,” she says. “We have this idea of band-aids and white saviors, but we are totally equipped to do the work ourselves. If we allocate the resources. We know us. We know our children.”

Another part of the advocacy work and the training that Urban Triage does is helping parents understand child development.

“We teach child development, we teach about different stages; how to interact, appropriate responses and what’s not appropriate. Why do we have maladaptive responses to our children? And then we connect it to our stories and history,” Grayson says. “Because during slavery, it wasn’t OK for your child to go running over there. They could get killed. It wasn’t OK for your child to be smart or to talk around white people. But we know that those maladaptive behaviors that back then saved our lives, are now hurting us. They are no longer applicable. So we have to be aware of that and change that. But we can’t change something we’re not aware of.

“That’s why we use the post-traumatic slave syndrome model. Because Dr. Joy DeGruy breaks it all down. It’s amazing. We’ve been desensitized towards the violence toward our bodies – seeing black bodies in the street and seeing black folks fighting and showing the violence in our community,” she continues. “By desensitizing us, it makes it OK, allowable and acceptable. When we don’t have the jargon, the language, the understanding, the analysis or the awareness of what’s happening, we end up perpetuating against ourselves.

Grayson says that her short-term goal for Urban Triage is to train enough parents to be part of the Rapid Response Team and to get the system up and running and people reporting incidents.

“Not only so we can send support, but so we can begin collecting real-life data,” she says. “School districts don’t tell us sh*t until weeks after things kick off. As a community we don’t know. That a little boy at Franklin Elementary School was hit in the head by a door … we didn’t know. That happened a long time ago. We had no idea. We didn’t know for 10 days about the situation that happened at Whitehorse.

“We need a place to collect this data – real-live data. And that’s what we plan on doing. Our long-term goals are to have rapid response leaders located near and in each school district. We will be right outside,” she continues. “And even be very present inside the schools. Instead of having the police walk the halls, have the rapid response people, the teachers, the parents there. Not only that, we’re economically empowering people. You pay them $25 to do the work, it’s an incentive. And you are providing them with all kinds of skills – mentorship skills, peer-support specialist skills. Why are we putting people who are not attached to the reality of the most vulnerable in these positions? We have everything we need.”