by Natalie Eilbert and Duke Behnke

USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin

Long Vue remembers eggs being splattered over his parents’ car after he and his family arrived in Kaukauna, Wisconsin in 1980. He recalls the vitriolic shouts from white residents telling them to go back to their homeland.

There was no homeland to return to for Hmong refugees. Vue’s family fled Laos after his father and uncle were active in protecting communication towers used to direct U.S. planes dropping bombs on North Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

After 42 years of living in the Fox Valley, he said the eggs returned with renewed fury. Now 54 and executive director of NEW Hmong Professionals, Vue said former President Donald Trump’s repeated use of the term “China virus” for the coronavirus fueled a rise of Asian American and Pacific Islander hate and scapegoating.

“We had a case where people were being egged again, and people were being vandalized at their place,” Vue said. “Our elderly are not feeling safe to walk in the street or go shopping because people were screaming at them and yelling at them to go back to their country.”

Though progress has been made toward understanding and accepting the Hmong and other minorities, integration, in Vue’s mind, has not yet been achieved.

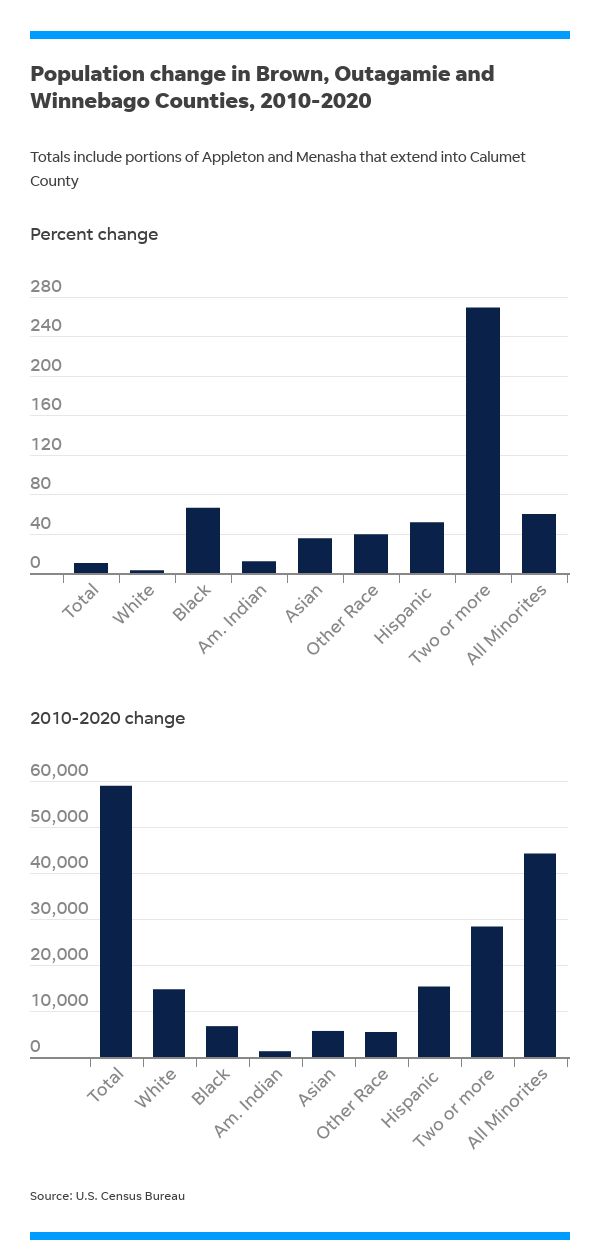

Stories like Vue’s smolder behind the neat and clinical 2020 U.S. Census Bureau data, which show that Black, Asian, Native American and Hispanic residents accounted for three-fourths of the population growth in Brown, Outagamie and Winnebago counties in the past decade.

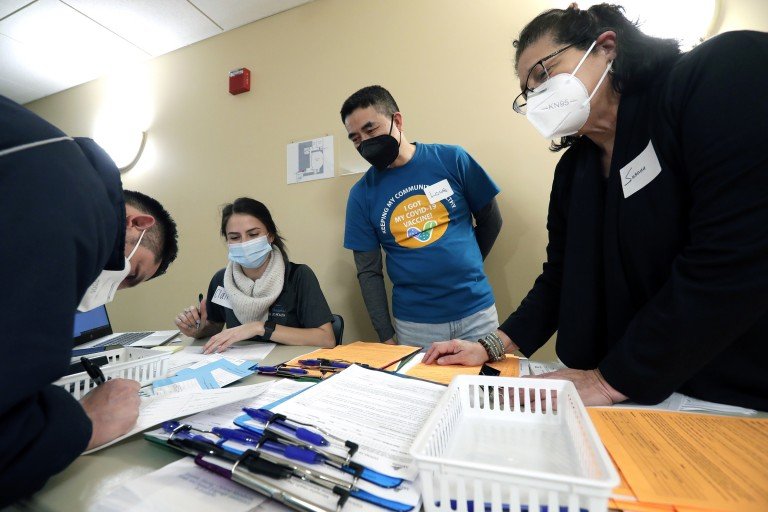

Dan Powers / USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin

The people who contribute to the region’s growing racial and ethnic diversity run the gamut, from professionals to shop, restaurant and business owners and their employees.

They include Indigenous people whose ancestors lived in the area well before people of any other backgrounds came to northeastern Wisconsin, and later arrivals of all races who were drawn to the region and remain here for any number of reasons including jobs, a lower cost of living than in major cities, low crime, and supportive organizations that help foster a sense of community and belonging.

That growing diversity is changing the face of the communities along the Interstate 41 corridor between Oshkosh and Green Bay, adding to their vibrancy, but it is not without challenges for those seeking a sense of belonging and acceptance in a region that can be slow to embrace change.

Since 2010, the minority population in these three counties — residents who are Black, Asian, Native American, Pacific Islanders, and from two or more races — has grown by 60%, from 75,000 a decade ago to 118,000 in the last count. At the same time, Hispanic residents, who can be of any race or combination of races according to the U.S. Census Bureau, increased by 46%.

By contrast, the non-Hispanic white population in these same counties has shrunk slightly, from 528,000 to 525,000.

A more detailed breakdown of the 2020 U.S. census data shows the key changes among each group:

Hispanic residents now make up 7% of the region’s population.

The region’s Black population increased 63% between 2010 and 2020.

The number of Asian American residents grew 30%.

The Native American population is also growing, albeit at a slower rate of 12%.

People who represent two or more races are, by far, the fastest growing group in the region, having more than tripled in number in the past decade.

For some, integration is part of the region’s ‘growing pains’

Jose Villa, 31, was drawn to Green Bay from a majority-white school district in 2008. His high school counselor in Sturgeon Bay encouraged him to seek out colleges in the Brown County area, citing more resources for people of color.

His school life in Sturgeon Bay was bracketed by hard labor to support his single mother, who emigrated from Michoacán in Mexico to join other family members who had jobs in the region. He started farm work at the age of 13, waking up at 4 a.m. to get in a couple of hours of work before heading to school by 8 a.m.

“That was everybody in my situation. We were told at a very early age to put on our big boy pants or our big girl pants and get to work. It wasn’t an option,” Villa said.

He still finds himself reeling from the trauma of his youth. From an early age, he said, he was in survival mode, working hard and living with fear that an immigration agent might at any time arrive at his mother’s door.

“People in the community see us laboring as hard as we do and think it’s normal. But it’s not,” Villa said. “The struggles we go through are not normal and the resources aren’t there for people in our situation.”

He now works as a commercial loan officer at Fox Communities Credit Union and bought his first home in Green Bay in May.

But even as he has set down roots, and has forged relationships with local Hispanic-focused organizations like Casa ALBA Melanie and the Latino Professional Association, he continues to feel “growing pains” when he tries to connect with white people and other community organizations in Green Bay.

Villa, with his background in finance, has been distributing flyers advertising a few upcoming financial literacy courses in Spanish at Salm Partners, American Foods Group and other manufacturing plants in the Green Bay area.

It’s part of his effort to support the Hispanic community.

“In every little bit of my spare time, I want to help a kid who looks like me and is struggling through the same thing I’ve gone through,” he said.

Like Villa, Timber Smith, 48, struggled to find a sense of belonging or community when he moved to Oshkosh in 1992 to earn a college degree at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh.

Right away, he knew he didn’t fit with the university’s white students.

The feeling was par for the course for Smith. He grew up in Milwaukee and attended middle school and high school in Whitefish Bay — commonly known to him and other students as “Whitefolks” Bay because of its racial composition. As part of Wisconsin’s Chapter 220 program, Smith and hundreds of other students from Milwaukee were bused to suburban districts to promote racial integration.

Smith said on a typical campus, college students don’t necessarily mix with city residents. That wasn’t the case for Black students at UW-Oshkosh. They befriended Black residents of Oshkosh, with the older residents acting like uncles to the students.

“I’m exaggerating a little, but it felt like you knew every Black person from Oshkosh to Green Bay because there were just so few,” said Smith, who now is Appleton’s diversity, equity and inclusion coordinator.

It might be an exaggeration, but in 1990, according to the U.S. census, only 435 Black people lived in Oshkosh, comprising less than 1% of the population of 55,000 at that time.

The makeup of the communities along the I-41 corridor has changed significantly since then. In the past decade alone, the number of Black residents in Brown, Outagamie and Winnebago counties has increased 63%, from 10,337 to 17,000, according to the 2020 census.

The change was even greater in Appleton and Oshkosh, where the number of Black residents increased 77% and 71%, respectively. The percentages reflect a gain of nearly 1,000 Black residents in Appleton and 1,500 in Oshkosh.

“I knew it had changed when you no longer knew the people,” Smith said. “I would see a lot of people of color, and I didn’t have any clue who they were. And that used to not be a thing.”

What’s driving the region’s change?

Raiya Sankari-Díaz, Green Bay’s diversity coordinator, cites a lower cost of living as a major motivator for families and individuals moving to the region. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the cost of living in Green Bay, Appleton and Oshkosh in 2020 was about 8% lower than the national average.

An affordable cost of living and readily available jobs attract new residents of all stripes. But the growth of community-based amenities, like a diverse array of religious options, and community programs, like those provided by the YWCA, We All Rise and Casa ALBA Melanie, help to encourage tolerance and acceptance. Programs like these cement peoples’ places in their communities.

Sankari-Díaz said the city of Green Bay also hopes to foster a community designed to not only attract a diverse population, but help those residents stay here.

“That makes everything, in terms of quality of life, that much more enjoyable for individuals,” she said.

Steph Guzman, 29, is an English language learner teacher at Howard-Suamico School District and Lineville Intermediate School in the greater Green Bay area. She moved to Green Bay in 1999 when she was 7 years old.

Like Villa, she wants Hispanic children to see a person like her in a leadership role.

Guzman’s parents came to the United States from Mexico before she was born, living first in Cicero, a predominantly Hispanic suburb of Chicago, until the daily toll of drive-by shootings led them to Green Bay, a far safer city with ample opportunity to find work.

While virtually everybody around her spoke Spanish primarily when she lived in Cicero, the school system in Green Bay was different. The teachers did not speak Spanish, not even in the rooms dedicated to English language learners.

The sense of being an outsider at Preble High School was clearest in the cafeteria.

“In the lunchroom, we’d call (tables) Little Mexico and then you had Chinatown. That’s the kind of language we used,” Guzman said.

After her father and mother separated when she was 14, Guzman understood she had a responsibility to help support her mother. When she was old enough to work, Guzman attended high school at night and worked during the day for KI, making plastic chairs for classrooms.

Growing up poor and always working, Guzman didn’t think college was attainable. A scholarship didn’t seem like anything someone like her could receive until a fateful meeting with a representative from Northeast Wisconsin Technical College showed her a pathway.

Despite her work ethic and her college-level smarts, Guzman’s cycle of daytime factory work and school in the evening meant she wouldn’t catch up to her college-graduating peers until her late 20s.

Northeast Wisconsin cities like Green Bay, where nearly one in five residents is Hispanic, have pushed to expand social programs to lift low-income families like Guzmans’ out of poverty and offer better opportunities for the next generation.

This couldn’t be more true for Analy Castro, 25, who recently left her job at Brown County Planning and Land Services to pursue nonprofit work with The Salvation Army.

Castro moved with her family to Green Bay from a town south of Oaxaca in Mexico when she was 3. She said her family benefited from programs like WIC (Women, Infant and Children) for nutritional and child-rearing education, the Hispanic-centered health clinic at NWTC and Society of St. Vincent de Paul in Green Bay for food and donations.

This assistance was crucial in setting the stage for her to pursue her career in the nonprofit world.

“I feel like coming from a minority group, we did get a lot of help,” Castro said.

The rapid growth of the Hispanic population is part of a national trend that demographers cite as a natural increase, growth that’s driven by an established population rather than immigration, said David Egan-Robertson, demographer at the Applied Population Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In other words, it’s the result of families like the Villas, Guzmans and Castros deciding to stay in the region and raise the next generation of northeast Wisconsin’s children.

Still, Egan-Robertson acknowledged that one reason for the rise in numbers for the Hispanic population and for other groups is increased participation in the 10-year survey, because of the U.S. Census Bureau’s improved system of gathering the information.

“In some ways, maybe the diverse population was there in 2010, but the way the Census Bureau captured it then, it really wasn’t giving the full scope of the race and population,” Egan-Robertson said. “In 2020 they got their act together and expanded the amount of data they captured.”

The data unearthed by the 2020 census likely reflects a more precise representation of the region, he said. The system updates, and the option to fill out the form online, allowed people of color who have been here for generations to be counted, sometimes for the first time. That’s particularly true for those of two or more races, where clearer explanations and more options allowed people to better reflect their heritage.

As he approached adulthood, Vue was tempted to take up roots far from his humble beginnings in Kaukauna. He was the first in his family to earn a college degree. To change his mind, he needed only to look at his family ties to the region.

He recalled stories of elderly Hmong who struggled with loneliness and mental health issues after they arrived in Wisconsin. They would stare out the window alone with little to hope for. Some died by suicide.

“Nobody’s around,” Vue said. “Everybody’s going to school and going to work. It’s not like in

Laos, where your family is running around everywhere. In this country, it’s freezing cold in winter.

“When I thought of that image of my mom — she’s single now; my dad passed away — I said no. I have to come back.”

We’re changing, but are we melding?

When she thinks back on her public school experience, Guzman understands that she and her classmates internalized school-based segregation. As with most schoolyard antics, what seemed funny then is clearly unacceptable now.

The way she slipped through the cracks during high school continues to be all too common for children of color, a failing that is reflected in the disproportionate number of Black and Hispanic youth who become involved in the juvenile justice system.

Guzman, having pursued a degree in psychology with an emphasis in cultural psychology, not only wants to diminish these odds for children of color; she wants to mentor them throughout this formative time in their lives. She works directly with families of color to help students navigate challenges and obstacles specific to their experiences.

“Some kids might not be able to go to school from 7:15 a.m. to 3 p.m., but that doesn’t mean there should be lower expectations for those kids,” Guzman said. “People who work with these students sometimes are the first point of contact at a time when these kids keep hearing ‘You gotta pull yourselves up by your bootstraps.’ Yes, you have to work hard, but not everyone’s starting from the same place.”

Smith, meanwhile, said he has experienced racial discrimination in the Fox Valley, but nothing reached the level that caused him to move away, as many of his colleagues did.

“This wasn’t new to me,” Smith said. “Whitefish Bay actually treated me worse than Oshkosh ever has treated me.”

Oshkosh and Appleton, where he now works, are among the most welcoming places in the region for people of color, Smith said. However, he said, that level of comfort can dissipate in some of the smaller communities. Smith, whose wife is white and whose daughter is biracial, has felt discomfort during outings with his family.

“There are definitely spaces you walk into and you can just feel — I don’t want to say they make you feel unwelcome, but they definitely make you feel like you don’t fit,” he said.

Smith, who has lived in the Fox Valley for nearly 30 years, said the American dream — the belief that anyone, regardless of their origin or social class, can attain success through hard work and sacrifice — isn’t necessarily a reality for people of color. Prejudice and ignorance can sidetrack opportunity.

“You can work hard and have grit and character and have a tan, and opportunities won’t be offered or may pass you by,” he said. “That’s where the frustration happens.”

Vue said it’s important for white people to understand and appreciate that the Fox Valley is home to minority populations like the Hmong. His children were born here and have little connection with Laos.

“I don’t think they dream of going back home because they don’t know home,” he said. “Home is here.”

The Hmong certainly are not the first refugees or immigrants to arrive in northeast Wisconsin. All ethnic groups — the Germans, the Italians, the Irish, the Poles, etc. — arrived for the same reason: the opportunity to make a better life for themselves and their families.

“We are all sharing the same space as the human race, a human being, to try to make our life better here,” Vue said. “Their rights and my rights are equal. There’s no Hmong taking my land or taking my job. This is our job together.”