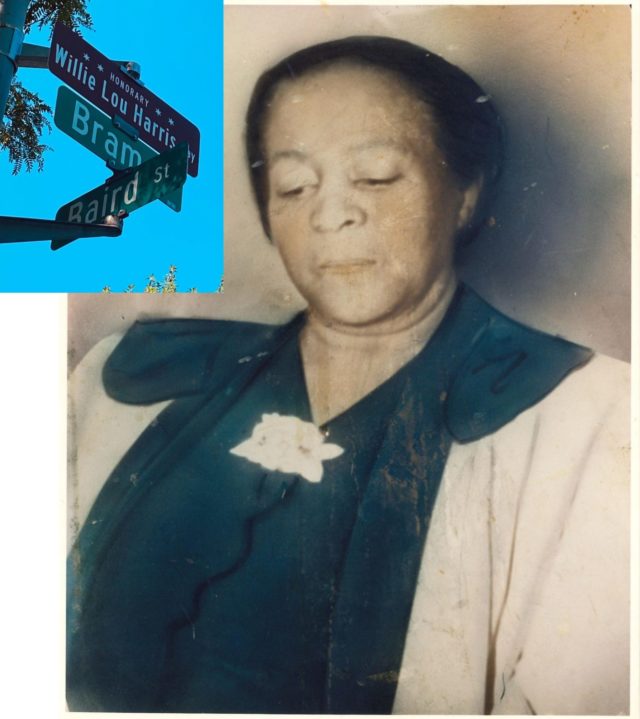

Family members, elected officials, non-profit leaders and the greater South Madison community came together on the afternoon of July 14 at the corner of Bram and Baird streets in South Madison to unveil an honorary street sign for Willie Lou Harris, a community leader in South Madison in the 1930s and ’40s and beyond.

Mrs. Harris, along with George Gerrard and Kenneth Newville, built the first neighborhood center in South Madison, which is now the Boys & Girls Clubs of Dane County.

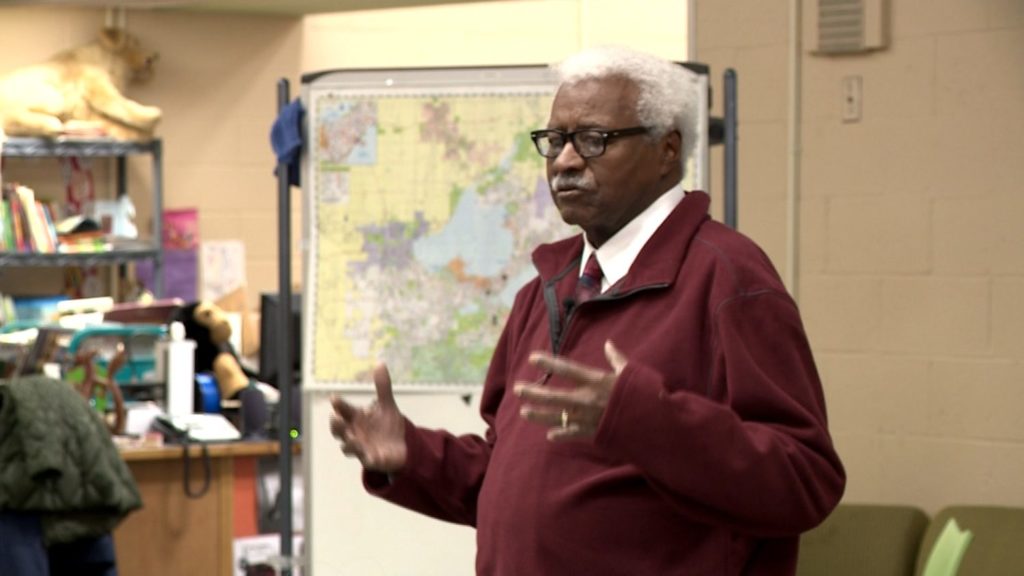

“I am so grateful. I know she’s smiling in heaven. She really worked hard and it’s so great for her to be honored,” Dr. Richard Harris, Willie Lou Harris’s son, tells Madison365. “The Boys and Girls Club runs that neighborhood center now and they do a terrific job. They do a tremendous job for South Madison and have a great number of programs. I know my mother is just looking down and smiling because they’re doing exactly what she wanted them to do.

(Photo A. David Dahmer)

“[Boys and Girls Club CEO] Michael Johnson is going to dedicate the interior entrance of the building to my mom — the area when you walk in where you have a waiting room and the lobby and all that,” he adds. “That’s gonna be renamed in her name. So we’ll be happy for that too.”

The new welcome center at the Boys & Girls Club will be called the Willie Lou Harris Welcome Center.

“To make sure her legacy lives, we’re going to set up a $100,000 endowment fund that will grow in perpetuity forever beyond our collective lifetimes,” Johnson said at the unveiling of the street sign.

Mrs. Harris was a passionate supporter of South Madison back in the day when the area was rural and there were few Black people in Madison. She was committed throughout her life to ensuring that everybody in the South Madison community would thrive. Dr. Richard Harris says that his mom arrived in Madison from a small city called Americus, Georgia. His dad, George Harris, came from Kentucky. They met at Mt. Zion Church.

“She met my father and they got married. Mom and dad bought some property in South Madison in the late 1920s and they paid $1,800,” Harris remembers. “They started out at $2,300 and my mother was able to negotiate it down.”

South Madison was the “pretty raggedy end of town” at the time, Harris says.

“It wasn’t located in the city, it was actually out of Madison. So in the area where they lived, they didn’t have running hot and cold running water and streetlights and it was really country,” Harris says of his parents’ new home. “So they raised pigs and cows and chickens and they had gardens out there. And in about four or five years after I was born, I would say about 1940, they were enacted into the city of Madison from the town of Madison. And so they had to get rid of all their farm things and animals.”

That area in south Madison didn’t have curbs and gutters and streetlights and things you’d find in a city yet. Harris says they used to call it “Hell’s Half Acre.”

“My mother and several other people began to badger the city to get them to get better things out there,” Harris says. “And my mother would do things for people like help them get a loan. In fact, my parents had to get their loan from the federal government. Because no banks would give them any money. They had to go to Chicago.”

Willie Lou Harris approached Chester Zmudzinski, director of the Madison Neighborhood Centers, and asked how can they could get a neighborhood center out in South Madison and he told her all the steps she had to take.

“She met with another guy from the university and they got her in contact with a representative from Wisconsin to a State Representative named Glenn Davis. He was a Republican who helped my mother. He talked the federal government into donating two barracks,” Harris says.

The US Air Force gave them two Air Force barracks from over by Truax, and Reynolds Moving and Storage company moved the barracks to Taft and Center Street in the heart of Madison’s south side.

“My mother got some guidance from people at Mt. Zion Baptist Church and some other different parts of the city and they came out and they would work on that building at night after work and on weekends until the center was built,” Harris says.

“Zmudzinski put them in with the Madison Neighborhood Centers and that’s where they got the money to run the programs,” he adds.

State Rep. Shelia Stubbs, who spoke at the honorary street sign dedication, says that the initial neighborhood center was so important for south Madison. She adds that the Harris family has been a truly instrumental part of the neighborhood for decades.

“I truly believe that Ms. Harris is a symbol of Black excellence in Madison. As the first Black licensed nurse practitioner, she demonstrated that women who looked like me can strive for professional exceptionalism, no matter the odds,” Stubbs says. “Even though the odds were stacked against her, she still strived to be so successful, and be someone who exemplifies Black excellence.”

At the dedication, Stubbs recited a quote from Coretta Scott King: “The greatness of a community is most accurately measured by the compassionate actions of its members.”

“Not only was Miss Willie Lou Harris a compassionate member of our community, but she put in the work to empower others to be just as compassionate. She brought individuals, families and young people to the table to create a community that was more than just the sum of its parts,” Stubbs says. “The greatness of South Madison is rooted in the people like Miss Willie Lou Harris who left a lasting legacy of cooperation that still endures today.

“I know with our permanent reminder of this Willie Lou Harris legacy we will be preserving a bright light on our path that will illuminate our progress in the future.”

Stubbs was also instrumental in honoring Harris in the Wisconsin State Capitol Building where she works. In 2020, Gov. Evers unveiled two new prints to be displayed in the governor’s office of important Madisonians, Willie Lou Harris and the Rev. James Wright

“I remember when I first entered the Capitol and was sworn in the Legislature in 2019. I walked every hallway and every entrance and I did not see myself in that Capitol and that was an issue. I didn’t see a portrait of anyone that looked like me,” Stubbs says. “So it’s so important to be able to advocate for historical photos to be displayed in the capitol building like that of Willie Lou Harris.

“Mrs. Harris is truly a symbol of Black excellence in Madison,” she adds. “She is so deserving of a honorary street sign.”