Law enforcement officers in Wisconsin kill people at among the lower per capita rates in the country. But some agencies including the sheriff’s departments in Marinette and Walworth counties have killed people at much higher rates since 2013.

“Police shootings — especially fatal ones — are statistically rare events,” Meghan Stroshine, an associate professor of criminology and law studies at Marquette University who studies law enforcement and use of force, wrote in an email. “Even in an agency the size of Milwaukee, you’re maybe talking a dozen shooting incidents a year, ‘only’ a couple of which will be fatal.”

Since 2013, law enforcement officers in Wisconsin have killed an estimated 143 people, according to a database from Mapping Police Violence, which tracks killings by police based on reports in the news media. That’s an average of about 15 people killed by police per year in the state.

The FBI also maintains a national database of use-of-force incidents by law enforcement, but reporting is not mandatory, so many agencies do not report and the data are incomplete, Stroshine said.

Among people killed by police in Wisconsin , about 27% were Black, although Black residents make up just 6.2% of Wisconsin’s population, according to data Mapping Police Violence prepared for The Badger Project. All but four of the 143 killed were men.

Most have been deemed justified by an outside agency or a district attorney and have not resulted in criminal charges against the officer, according to the cases gathered by Mapping Police Violence. Law enforcement said the victims were armed in more than 75% of the deaths. Nearly all were killed after being shot by police; a few died by other means.

In Wisconsin, the number of police killings spiked in 2017 at 26, and bottomed out at 10 in 2014, but the trend has stayed relatively stable.

Wisconsin below national average

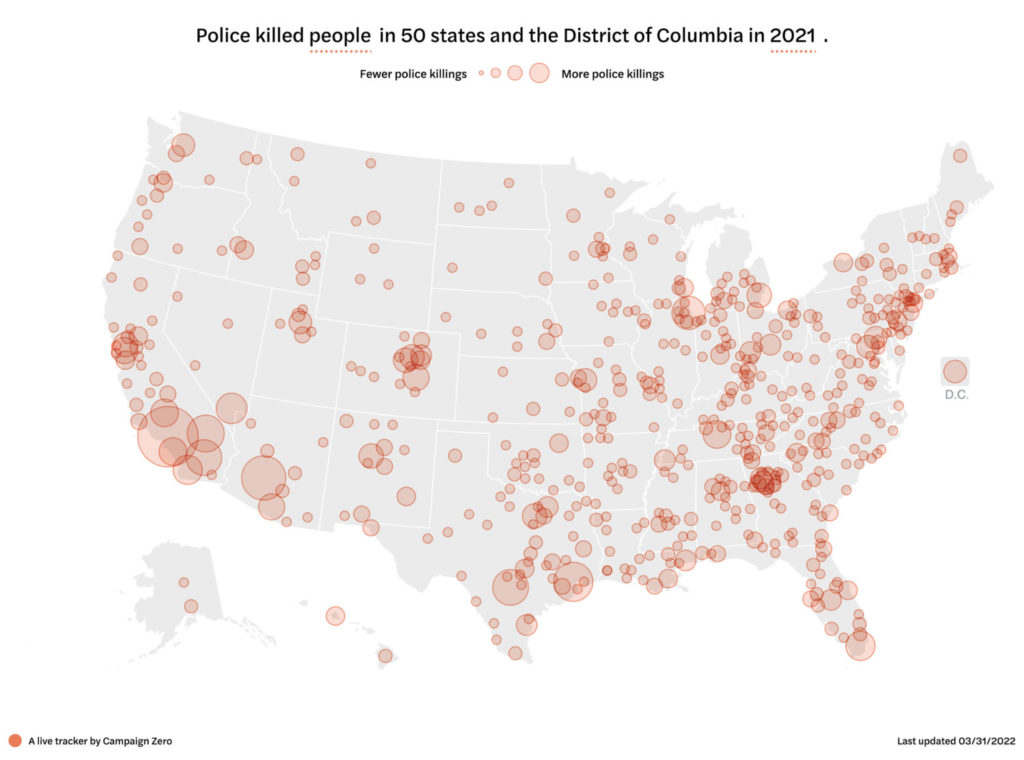

Nationally, law enforcement killed about 3.3 people for every million per year from 2013 through 2021, according to Mapping Police Violence. The annual average of police killings in Wisconsin in the same time frame is about 2.7 per million inhabitants, putting the state 36th nationally.

Starting from the most, New Mexico, Alaska, Oklahoma, Arizona and Colorado killed people at the highest rates in the country, between about 6 and 10 per million people per year, the data show. Starting from the least, law enforcement in Rhode Island, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Jersey killed people at the lowest rates, between .8 and 1.5 per million people per year.

Nationally, police kill about 1,100 people per year, mostly from shootings, according to the Mapping Police Violence and a similar database maintained by The Washington Post. Despite increased attention, that number has stayed flat in recent years.

Some analyses suggest police killings in urban areas, mostly of people of color, have decreased in the past decade, while killings by police in suburban and rural areas, mostly of white people, have increased.

Jim Palmer, head of the Wisconsin Police Professional Association, the largest police union in the state, said he was not surprised that Wisconsin is in the bottom third of per capita killings by police.

“The training that officers receive in Wisconsin is ahead of our peers nationally,” he said.

Palmer pointed to the scenario-based training that all law enforcement cadets now receive at the academy. In 2016, the state increased the amount of this training that cadets must complete from at least 60 hours to approximately 110 hours, said Stephanie Pederson, an educational consultant at the state Department of Justice.

Palmer also noted that in 2014, Wisconsin became the first state in the country to mandate that an outside law enforcement agency conduct investigations of officer-related deaths. Republican Gov. Scott Walker signed the bill, which had been pushed by Michael Bell Sr., whose namesake son was killed by Kenosha Police during a traffic stop in 2004. Critics across the country have long bemoaned the conflict of interest of having law enforcement agencies investigate their own officers.

And since 2020, the Wisconsin Department of Justice has collected data on use of force incidents from law enforcement agencies and recently launched a database for public use.

Why police kill, and why rates differ

There are “only two situations where deadly force is acceptable or allowable,” said Christopher Herrmann, an assistant professor of law and police science at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “If the officer feels like their life, or someone else’s life, is threatened.”

Fatal shootings by law enforcement tend to have several things in common, Stroshine said. The majority involve male victims who are armed and have a drug addiction or a mental health issue, she said.

And use of force policies can differ greatly across agencies, Stroshine noted.

“What might warrant a particular level of force in one jurisdiction may be very different than what would warrant that same level of force in a different jurisdiction,” she said. “Some policies would allow officers to shoot at moving cars while some policies would definitely not allow that.”

Officers in suburban and especially rural areas are often working alone in places where gun ownership might be higher, Stroshine said. And big-city police departments usually have more funding for extra training and other resources that could decrease killings by police.

Patrick Solar, an associate professor of criminal justice at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville and a former police chief, said some law enforcement agencies focus more on law and order, while others are more concerned with reducing police violence.

“The police are a reflection of community expectations. That’s always the case,” Solar said. “You’ll be able to explain a lot of the variance in per capita police killings based on that.”

Solar continued that the question in every incident is, were there alternatives that could have been exercised by the officer to avoid having to take a life?

“Some officers are not aware of those alternatives,” he said. “It’s not a part of their training, it’s not a part of their culture.”

Higher numbers at some agencies

Unsurprisingly, the three biggest cities in Wisconsin have seen the most killings by law enforcement, according to Mapping Police Violence.

Milwaukee Police have killed 23 people since 2013. Madison Police have killed seven people in the same time frame, while Green Bay Police have killed six.

Some cases involve incidents in which there is little question about the need for use of force. Bruce Pofahl, one of the people killed in 2021 by Green Bay Police, had just shot three people, killing two of them, at a hotel connected to the Oneida Casino.

In a 2019 case, Javier Francisco Garcia-Mendez died after Green Bay Police tasered and handcuffed him following reports that he was pounding on doors and chasing people. He was unarmed, but had bitten a woman, police said.

Marinette County Sheriff’s Department

Marinette County Sheriff’s deputies have shot and killed five people since 2013, a high number of police-involved deaths for a county of only 42,000 people.

Two of those victims had just shot and killed another person, and all five were armed with a gun, the sheriff’s department said.

“I think it’s just been a cruel twist of fate to our agency,” Marinette County Sheriff Jerry Sauve said. “I think that the circumstances presented themselves, and our people were in harm’s way, and that was the end result.”

Three of the five killings involved multiple officers shooting the victims. Deputy Jesse Parker fired his weapon in three of the killings, and Deputy Steve Schmidt in two.

“We’re a small department,” Sauve said. “Those two particular officers are also part of our special response team. In a couple of those, they were there in that role.”

Unlike some of the larger law enforcement agencies in the state, the Marinette County Sheriff’s Department does not employ any mental health crisis counselors, Sauve said. In the midst of a statewide shortage of law enforcement officers, Sauve said his department is struggling to fill positions at the county jail, and sometimes has to use patrol deputies there just to staff at legal minimums.

Walworth County Sheriff’s Office

Similarly, deputies from the Walworth County Sheriff’s Department have shot and killed five people in the last decade.

One was incarcerated at the county jail. Deputy Richard Lagle shot 18-year-old Alfredo Emilio Villarreal, saying the man had attacked him and was trying to escape while at the hospital. In another case, Kris Kristl aimed a BB gun at a county deputy and an Elkhorn Police officer.

In an email, Undersheriff Dave Gerber wrote, “Every case of a fatal shooting involving one of our deputies has been reviewed by a District Attorney, and in every case the District Attorney has determined that the enforcement was privileged and a reasonable exercise of self-defense and/or the defense of others pursuant to Wisconsin Statutes.”

Two of the victims were driving vehicles when they were shot and killed. Gerber said in both situations, the deputy was unable to get out of the way. Law enforcement are generally trained to approach vehicles from the rear or side to avoid standing in its path, experts say.

“These situations evolve rapidly and although not specifically stated in our Use of Force Policy, our deputies are allowed to defend themselves (or another person) when the deputy reasonably believes they are in imminent danger of death or great bodily harm,” Gerber wrote in an email. “A vehicle about to strike them is an imminent danger of death or great bodily harm.”

Some law enforcement agencies have restricted the practice of firing at a moving vehicle, because shooting the driver doesn’t always stop the vehicle and could make the situation worse. An officer can shoot passengers, for example, or hit the driver and turn the vehicle into a battering ram, endangering bystanders.

This practice is “increasingly viewed as an unnecessary risk,” Stroshine said.

“Many reformers have called for a complete ban on shooting at moving vehicles, and some departments have moved in this direction,” she said. “Restrictions are necessary; however, a ban may go too far. Officers should be required to retreat or avoid shooting at moving vehicles whenever possible.

But, Stroshine added, “there may be situations when an officer reasonably believes there is no other alternative or the vehicle has taken aim at the officer or others.” She cited the 2021 case of Waukesha Police who shot at Darrell Brooks as he barreled through the city’s Christmas parade, killing six and wounding more than 60 others with his SUV.

“It should be the last resort,” Stroshine said, “but officers should have that option if they deem it necessary.”

Waukesha Police Department

Waukesha Police officers have killed four people in the past decade.

Two of the victims were armed with guns and one had a knife, the department said. The fourth, an unarmed man who police said had hit his girlfriend and resisted arrest, was tased multiple times and kicked by police and later died in custody.

Waukesha Police Captain Dan Baumann noted that independent reviews concluded that all the killings were justified.

“It is tragic,” he said. “We don’t want deadly force encounters.”

The family of one of the armed men, Randy Ashland, filed a wrongful death lawsuit in 2020 against the Waukesha department and the two police officers who shot him. The family claims Ashland was holding the gun by the barrel and didn’t point it at officers. Several other officers on scene did not fire at Ashland, the family argues. The suit is still moving through federal court.

The police department doesn’t comment on pending litigation, Baumann said.

The department sometimes uses a county-employed crisis counselor, and plans to embed another at the city level are in motion, Baumann said. Waukesha Police have not used body cameras, but hope to deploy them to every officer in the field by October, he said.

Eau Claire Police Department

Officers with the Eau Claire Police Department have shot and killed four people in the past decade.

Officer Kristopher O’Neill, who has worked for the department for about 25 years, has shot and killed two people in the past five years. In 2021, the victim LeKenneth Miller had just stabbed a woman and refused to drop a knife, police said. The other, Matthew Zank in 2017, called 911 to report an armed man, then pointed a gun at officers when they arrived, police said. Zank had a note in his wallet apologizing to the police officer who killed him, police said.

Eau Claire County District Attorney Gary King ruled O’Neill was justified in both shootings.

Per state law, all four killings were investigated by outside agencies, in these cases the La Crosse Police Department and the Wisconsin Department of Justice, Eau Claire Police Lt. Ben Frederick said.

Frederick said the Eau Claire Police Department employs a community policing philosophy that prioritizes partnerships and problem-solving. He noted the department posts its reviews of use of force incidents on its website.

“The officer’s role is as a community partner and guardian of peace and freedom,” he said.

Frederick also mentioned the department launched a Mental Health Co-Response program in 2021 to bring clinical intervention workers into some police encounters and has incorporated crisis intervention into quarterly use-of-force training.

Marathon County Sheriff’s Office

Deputies from the Marathon County Sheriff’s Office have shot and killed four people in the past decade. The sheriff’s office said all four were armed, three had fired at people, two had shot officers and one had killed Everest Metro Detective Jason Weiland and three others.

Marathon County Sheriff Scott Parks noted that law enforcement made “many efforts in each event to negotiate a peaceful resolution in these incidents.”

Detective Brandon Stroik, a military sniper, was a shooter in two of the four, including one man who was holding another hostage at gunpoint, the department said.

As a first responder, Stroik “responded to the active incident, placing himself in harm’s way, which is what we would expect him to do,” Parks said.

New approaches eyed to lower deaths

Because mental health disorders can be a large part of modern policing, and often an issue in police killings, some local governments and law enforcement agencies across Wisconsin are trying different strategies to lower the chance of a fatal encounter.

The city of Madison and its police department have been leaders in this area, experts say. The police department has deployed mental health workers since 2004, a practice other agencies have followed. It city has also pioneered the use of teams of EMTs and mental health professionals to take some pressure off police as well as those in need.

And in September, Milwaukee County will open a mental health emergency center in the city’s downtown where law enforcement police can bring people in crisis, said Edward Fallone, a Marquette law professor who chairs the citizen board of the Milwaukee Police and Fire Commission.

The type and amount of training law enforcement officers get can also reduce the need to use force, experts say. Some credit virtual reality scenario-based training with helping officers make good decisions in tight situations.

“You’d be hard pressed to prove it, but I would wager a month’s worth of my meager salary that that has made a great difference in terms of officers being able to deal with use of force situations,” said Solar, the UW-Platteville professor. “The fact is the more of that kind of training you get, the less reactionary you’re going to be, the less fearful you’re going to be and the more confident you’re going to be.”

In addition to their training at the academy, officers in Wisconsin must complete 24 hours of continuing education annually, Pederson said. But they can always do more. Waukesha Police officers complete at least 60 hours annually on a variety of topics, Baumann said.

Avoiding use of force

One type is nonlethal weapons training. Many law enforcement agencies across the state have increased their arsenals of nonlethal weapons, including devices that shoot beanbag rounds, foam projectiles and even kevlar bola wraps, Eau Claire County Sheriff’s Department Capt. Cory Schalinske said.

But comparatively, officers still receive far more training on firearms skills and defensive tactics than they do on nonlethal weapons, Stroshine said. In fact, officers spend more time in firearm skills training than they do being trained on ethics, communications skills, cultural competence, critical thinking, decision-making, and crisis management combined, she said.

“While officers must be prepared when faced with a lethal threat,” she said, “officers need to be far better educated on how to avoid the use of force in the first place.”

At the academy level in Wisconsin, law enforcement cadets receive 68 hours of firearms training, two of which are “deadly force decision making.” They receive 52 hours of training on ethics, communication, cultural competence, critical thinking, and crisis management.

Of course, finding funding for mental health professionals, nonlethal weapons and additional officer training can be a problem for any agency, especially smaller ones, experts say.

Fallone said any “one action isn’t going to have major results.”

“It’s got to be a multifaceted approach to, how do we transform interactions between the police and members of the public to reduce the risk that those interactions spiral out of control and result in a police shooting?” he said.

Reporting this story for Wisconsin Watch was Peter Cameron, managing editor of The Badger Project, a nonpartisan journalism nonprofit based in Madison. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (wisconsinwatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.