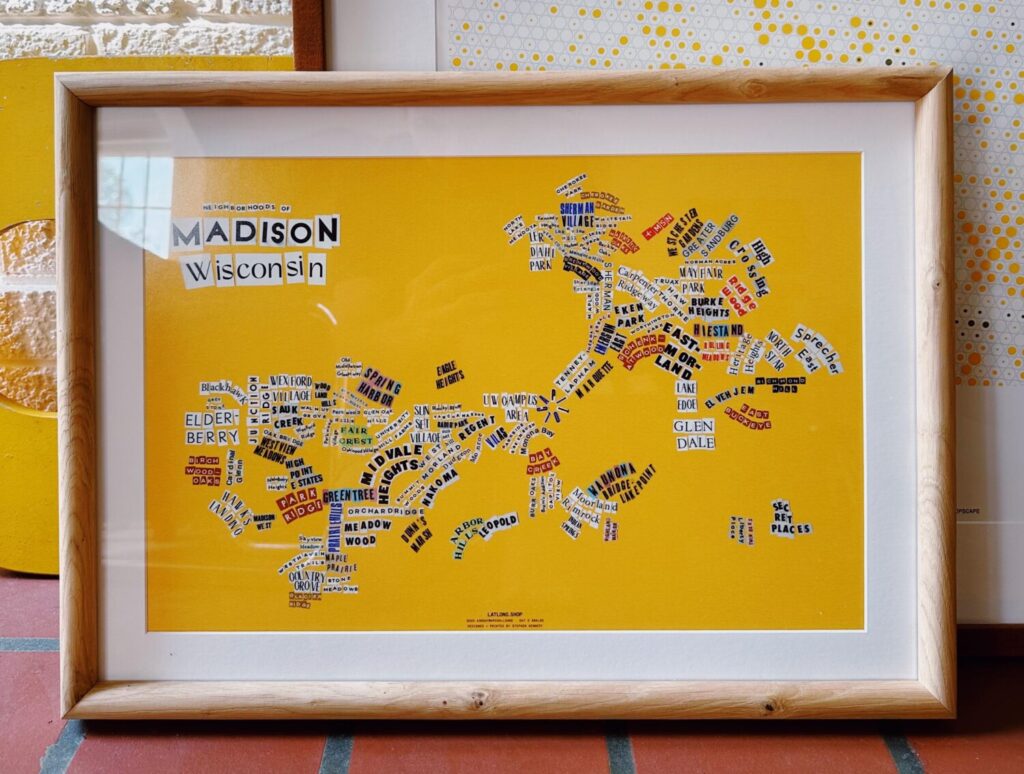

If you frequent the artistic stretch of the Dane County Farmers’ Market on State Street, it’s likely that a map or two of Madison has caught your eye. A staple at spring and summer markets around Madison, LatLong.Shop is a creative cartography business owned by Stephen Kennedy that is rethinking the stories we tell about our beloved city, one map at a time. Finding the sweet spot between utility, data, and aesthetics, Kennedy’s detailed and expressive maps are finding new ways of painting a picture of Madison, whether through its neighborhoods, agriculture, or geological genealogies. “Every map speaks to everyone differently,” Kennedy says, and his creations prove just that: Maps aren’t just for getting you from one point to the next. They’re about finding new lenses through which to see the world around you, making what might otherwise feel ordinary and familiar a place of wonder and discovery.

Madison365’s Rodlyn-Mae Banting spoke with Kennedy ahead of his Bubbler artist residency with Madison Public Library, during which his exhibit “Atlas of an Isthmus: Creative Cartography of Madison & Beyond” will be on display at the Sequoya Library through December. An opening reception will take place on Thursday, Sept. 5 at 6:30 p.m.

RB: How did you get into cartography?

SK: As a professional practice it started in two phases. I went to design school in undergrad [which gave me a] more traditional product design experience. I learned to build furniture, to design a toaster, and just the general practice of design as a discipline. Shortly after graduating, I felt pulled in a different direction. I had taken a course in New York over the summer in community mapping and understanding the needs and conditions of a community by gathering data and trying to understand a place by creating a map as an artifact. That got me really interested in the urban planning discipline world, and so I ended up pursuing a master’s degree in urban planning. That was really a chance to think about taking the craft of design and applying it to a specific arena like community development and the way our cities and communities are developed through planning. I ended up focusing mostly on visualization tactics that help facilitate planning.

Fundamentally, all these things are very complex as systems. Part of the ethos of planning as a discipline is community engagement. How do you incorporate community voice and community perspective into the planning world? And for me, the hypothesis was that visualization and maps can play an important role in that. Your typical person living in the neighborhood may not think about dwelling unit density in their area, but understanding a little bit more about that may help how they inform participating in public processes related to the development.

RB: Could you talk a little bit about cartography as an art form? Do you feel like it’s something that’s still in the general public?

SK: I’ve only thought of myself as having an art practice as of the last two years. Up until that point, I’ve always framed myself more explicitly as a designer. So it’s definitely been something I’ve kind of been learning and feeling and understanding more about myself. What’s been great about LatLong.Shop and that being an expression of cartography as an art practice is the community engagement element and talking to people about maps. Just like other forms of art, every map speaks to everyone differently, and they have different interpretations. And from the variety of maps that I present, there’s always one that catches someone’s eye and stands out because they have some personal relationship to the concept or the content. Setting aside the maps we typically experience in our phones and that sort of thing, I do think maps are becoming more prevalent as a general communication form.

The maps that I create as an art form, I definitely view them as straddling the line between practical [and aesthetic]. They’re still attempting to be accurate to a certain degree. There’s a data rigor that still goes into them, even though the final output may be purely visually expressive of a concept.

RB: When did Madison and Wisconsin more broadly become your subject?

SK: Part of it is personal life trajectory. My partner grew up here, and he and I were living in New York City when the pandemic hit. His family was still out here, and so given timing and life circumstances, it made sense to consider leaving New York and moving here. And for me, the Midwest was a totally new environment. I grew up in the metro Atlanta area and have lived on both coasts over the past decade. I’ve loved it so far [and it] definitely feels like a place where we’re putting down roots and we’ll be here for the long haul. On a personal note, my paternal grandparents are from Wisconsin. My grandpa grew up in the Vilas neighborhood and went to the same high school as my husband. It’s kind of a full circle thing, even though I didn’t know or feel that I had a personal connection to Madison, because they didn’t live here when I was growing up. It’s been really cool to come full circle from, like a familial perspective.

In terms of how Madison became my subject, it started in fall of 2022. I was seeking something creative to do and I found online that there was this social media challenge called the 30DayMapChallenge that was started by a cartographer based in Finland named Topi Tjukanov. It encourages cartographers across the world to produce a series of maps for every day of the month of November, and there’s a series of prompts for every single day. And I was like, “Sure, I’ll give this a go.” It had been a while since I just did a free-form project not tied to my professional work. I don’t know that I thought about it very hard, but given that it seemed like a daunting task to [create a] map so quickly every single day over a month, I set for myself certain parameters, the main one being that I was just going to do maps of Madison. [I used] it as a way to better understand this new place that I’d been living in for a year, that I had family ties to, but didn’t know much about. Often one of the first exercises you do as a planner is ground-truthing [and] understanding the current conditions [of a place]. It’s a way of unpacking the place that you’re studying or analyzing or supporting.

RB: Could you walk me through the process of creating a map?

SK: Many folks who come to the booth [will say], “Oh, what if you did a map of X or a map of Y?” And oftentimes those are great ideas and I think would be really interesting maps. But really, what it fundamentally comes down to is, does the data exist to execute it? So oftentimes, my process is really starting with finding a data set and determining what might be possible to show from that data set as opposed to coming up with the concept and then trying to pin down the data. So my general process [is that] I kind of have a running list of data sets that I think could work with that come from different sources. There are a bunch of state agencies that have public data portals. I use the platform OpenStreetMap quite frequently, which is a community source-based [platform] for data. And then over the past two years, I’ve really been using that 30DayMapChallenge to spark a concept and connect data that might fit that concept. And after I produce the series in November, I’ll work towards refining a few of them that I think are well suited to a print experience. And in the spring and into the summer of market season, I’ll refine those as print designs.

RB: What are the most exciting or surprising things you’ve learned about Madison in making these maps?

SK: One of my favorite maps still, to this day, was one of my first in the series two years ago. It’s a map that depicts the corn acreage density and compares that to the population density. Visually, I think it came out so simple. It’s not a complex visual necessarily, but I think that [it’s about] the narrative of juxtaposing those two things and seeing them at scale. Just recognizing that even though we think of Madison as this dramatically growing place, there’s still so much agriculture that surrounds us, and this visualization still hits that home. Obviously, it’s not going into the nuances of where farms are being turned over in suburban areas and whatnot, and that’s absolutely part of the narrative of development here, but it’s this step back of recognizing that we’re still an agricultural community and the corn is very present. Everyone knows this, but seeing it at scale on a map sparks that reminder for folks and that general understanding.

The thing for me that has been really interesting to better understand about Madison as a place is our geologic place in the world. I think for folks who grew up in the Madison area, or have some general interest in geology, they kind of know of some of the highlights of the area—that we’re adjacent to the Driftless; that there are glacial drumlins; that there are all these various landforms that exist around us; that our lakes were formed because of the glaciers—that really make it a hotbed of these interesting geologic time references…we’re talking tens of thousands of years. We’re really at the edge of these two dramatically different landscapes that were formed by the presence or lack thereof of the glaciers that have subsequent effects that we see the landscape today. I have one map that shows the extent of the glaciers across Wisconsin, and then another map that shows current tree coverage across the state. And you can actually see visual ties between the two: the glacial lobe that occupied the eastern part of the state, that area is dramatically less tree-covered compared to other parts of the state today.

RB: I was very interested to learn that you had only really considered yourself an artist over the past two years. I’d love to hear a little bit about how you feel like you’re able to channel other parts of your identity or personality in creating these maps.

SK: I’ve been reflecting a bit about this recently and trying to remember elements of my childhood. I found old maps that I must’ve drawn when I was four or five and I’ve always had that as part of my way of understanding the world. From an identity perspective, my mom immigrated to the US from the Philippines in the 70s, and originally, she moved to Florida with her sister and worked there. Then when I was born [and] my brother was born, we eventually moved up to the metro Atlanta area. I grew up in this suburban environment in somewhat of a hyper-religious conservative environment, and as a queer person, I always felt a little bit removed and out of place from it. For me as a child, expressing myself through maps was a way to explore the broader world around me when I didn’t always feel like I connected to the place I was in at the time. I don’t know exactly what I was thinking when I was ten years old or five years old, but I think in hindsight, I feel like it must have been a way for me to see what was out there and to understand it. Traveling to the Philippines with my mom and our family was some of my first international experiences, and it kind of gave me that bug of wanting to understand other cultures, other places, and maps have really become a lens for doing that. It all ties back to culture and experience in a way that maybe I didn’t connect the dots until more recently.

RB: What do you hope community members will take away from your Bubbler exhibit?

SK: I think it’s a great honor, and I’m so thankful that they have this program. I’ve operated in this outdoor market every single Saturday over the past two summers downtown, which has been so fun, but it comes with its own physical practicalities and impracticalities. So I just love the idea of being able to have work on display for an extended period of time, and in particular, I’ll actually be able to show larger format pieces that are just impractical to bring downtown. For me, it fundamentally comes down to having more interesting conversations with community members in reaction to the maps. What does this map say about our geology, our history? What does it tell you about the place that you live in and how you think about it? It’s such a powerful way to just learn about my context through the conversation—not just the generation—of the map. And because the Sequoya Library will be an early voting site the maps will be here and will be present. You know, during this heightened period of people visiting the library for a very critical act of voting, [I’m excited about] what dialogue it sparks as people are participating in this critical element of democracy.

I’m also planning to facilitate at least one type of workshop program [during the residency]. The current plan is to teach people to do neighborhood mapping through collage. And so the prompt will be to think about your own neighborhood, and what stands out about it. Last year I hosted a map-a-thon [that] was basically teaching people how to contribute to the platform OpenStreetMaps and edit data and add data. And we honed in last year on the theme of bike infrastructure and making the source data not just about cars as the primary way we operate our own cities and move around cities, but making sure that there’s equal representation of these other transit forms in this open source platform.