by Seth Freed Wessler, ProPublica

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

In July of 2021, a professional architectural historian named Erin Edwards delivered what she expected would be the near-final draft of a report about a contested swath of sugar cane plantation land along the Mississippi River in Louisiana. The painstaking survey, for her bosses at a consulting firm, was supposed to identify harms to historic sites so that developers can prevent or minimize them.

Edwards’ report detailed how a proposed $400 million grain elevator, almost the height of the Statue of Liberty, would disrupt sites that are both sacred and dedicated to educating people about slavery and its aftermath. These included homes in the 750-person community of Wallace, an African American cemetery and the nearby Whitney Plantation Museum, which serves as a memorial to generations of people forced to work the fields against their will. The draft said vermin, loud noises and ground vibrations would likely invade the quiet space of the museum, which draws tens of thousands of visitors each year.

For many residents of Wallace and nearby communities in St. John the Baptist Parish, the site holds deeper meaning. They are the descendants of people who’d once been enslaved there.

An agricultural company called Greenfield had purchased the land for $40 million in 2021 and is seeking a permit from the Army Corps of Engineers to build a massive industrial operation that would include 54 grain silos. A long conveyor would carry millions of tons of wheat, soy and other crops to the facility from ships docked on the river. Gulf South Research Corporation, where Edwards worked, was hired to help Greenfield comply with a section of the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act that requires development projects funded or given a permit by federal agencies to document significant sites and come up with a plan to minimize harm. The law gives agencies like the Corps authority to deny permits if a proposed project cannot be reshaped to avoid harming sites with historic significance.

The draft report by Edwards and a co-author concluded that the grain elevator would have “an adverse effect on historic properties.” The authors said they had determined that the entire area should be listed as a historic district in the National Register of Historic Places, the federal government’s roster of sites deemed worthy of preservation.

Edwards had included a sentence that she believed was suggestive if not definitive about an underexamined aspect of the land: the possibility that it contained as-yet undiscovered graves. “Thus far, no enslaved cemeteries have been found for either Whitney or Evergreen Plantations,” another nearby and unusually intact plantation where the movie “Django Unchained” was filmed, “despite hundreds of enslaved people being kept there for over 155 years.”

Three months after Edwards handed in her report, in October 2021, Gulf South filed to the state a document with the same title as the one Edwards wrote but with some notable edits.

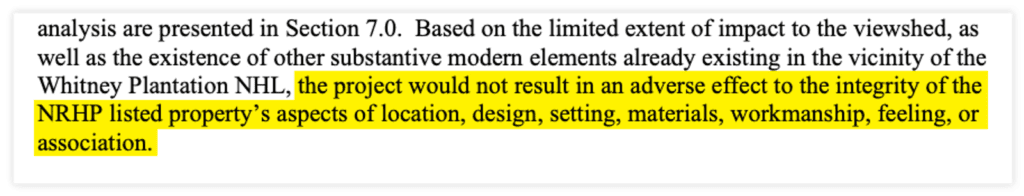

The determination of the historic district, the findings about the impact on Whitney and the community around it, and the lone sentence about unknown graves had all been removed. The report now concluded that “the project would not result in an adverse effect.”

The rewrite came after the contractor Greenfield hired to handle the permitting process pressured Gulf South, according to emails obtained by ProPublica. Gulf South was warned that if the firm didn’t take out Edwards’ key finding — that the entire area was a historic district — it would lose the contract.

“They are refusing to accept it,” Gulf South’s head of cultural resources, Mike Renacker, wrote about Edwards’ report in an email to an internal team. “They are willing to tear up the contract and fire us.” As written, the report “has the potential to not only cost us our contract and future work, but might end the overall project as well.”

Edwards was shocked. “It is unethical for a client to tell us what our findings are,” she replied in an email. “They came to us for our expertise, and they got a professional report that is factual.”

“Our reputation will be that we can be bought,” she added.

Renacker replied: “I’m not suggesting, nor would I ever suggest that we do something unethical. I’m not questioning your methods or even the recommendation. What I am doing is laying out the problem we are having and asking for help to find a solution.”

After Edwards’ bosses changed her report, she resigned from her job of seven years.

Gulf South wrote in response to questions from ProPublica that it “was not required by Greenfield or anyone else for that matter to make changes that GSRC does not support.” What Edwards submitted, the company said, was a draft, and it’s not uncommon for drafts to change after clients review them and offer new relevant information.

The company says it asked Edwards to provide additional evidence to support her conclusion that the area should be considered an historic district, but she “was unable to provide data needed to meet the referenced listing criteria.” Edwards, who has a master’s degree in preservation from Tulane, said that she was confident her report was comprehensive and that the state’s historic preservation office would have agreed, had that agency been sent the complete report.

Greenfield did not answer a number of detailed questions about the Gulf South surveys but said that it prioritizes the protection of historic sites, and that it would halt work in any area where construction discovers unknown cultural resources.

The contractor Greenfield hired to handle the permit process, Ramboll Group, declined to answer questions, stating that media requests should go to Greenfield and Gulf South.

Experts in the field of cultural resource management say that companies sometimes look away from findings or are asked to change them to make their developer bosses happy. The field is now dominated by for-profit firms like Gulf South that developers hire to comply with the federal law. As a result, these firms can operate not as preservation gatekeepers but as lock-pickers for private industry intent on development.

“There is little incentive for companies to find anything,” explained Tom King, who during the 80s was the director of the federal Office of Cultural Resource Preservation, under the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. “They’re not hired to find things. If they make construction impossible, they are not going to get more work.”

The community of Wallace, which is almost entirely Black, sits along a rare stretch of undeveloped riverbank south of Baton Rouge that’s not been transformed by polluting petrochemical plants and other heavy industry. Right off River Road, an 83-year-old woman named Clementine Grows sat on the porch of her small cottage, which was still covered in blue tarps after severe damage from Hurricane Ida last year. On this May morning, before the midday heat set in, she explained that she’d spent some of her childhood on the Whitney Plantation. From the dead-end road where she lives, Grows can see the plantation property, several hundred yards across a cane field.

Her grandparents had labored and lived on the Whitney, where wage workers were bound through credit to the plantation store, a whole century after the Civil War. They had cared for Grows, she said, after her mother was injured in a cane fire. She and her husband raised their children in Wallace. Grows worked as a cook at the local high school. Her husband worked at a grain elevator across the river. Her son, who was visiting Grows on that May morning, recalled coming home from school years ago and earning pocket change picking vegetables.

Grows said she did not know exactly what the grain elevator would mean for her and her home. She’s heard some people in her community say that the project would make it difficult to remain in these houses. “A lot of people say it’s going to cause all sorts of problems.”

Three decades ago, another company had nearly begun building a plant on the same land. She’d prepared to leave. But the plans were scrapped. “If we had to move all of a sudden that would be something. I’ve been here. My daddy was living right there,” Grows said. “All these people on this little land are kinfolk.”

Edwards had listed Grows’ house among several in a small enclave in Wallace called Willow Grove that should be considered part of a larger rural historic district, “as it was built for and used by the descendants of freed plantation workers.” At the end of Grows’ dead-end road, beyond a cleared grassy plot and adjacent to the planned grain elevator, a cemetery with about 50 stones bears names of people who died here, including Grows’ mother, Lorenza Poche, born in 1910, and her husband, Melvin Grows, an Army veteran, as well as one of her sons, four siblings and a grandson.

Grows recalls that decades ago, families would ask to bury their deceased relatives in areas near existing graves. Her neighbors who managed the burials, all of whom Grows said have now passed away, would sometimes tell them that there were open spaces that were off-limits to new interments. “When someone would come to bury someone there, they would say, ‘You can’t bury them there because someone’s been buried there already.’ And they’d find another place to bury them.”

It was her understanding that people had been buried there without headstones.

There is no mention of these or any other possible unmarked burials in the report that Gulf South sent to the state.

Shortly after Gulf South changed Edwards’ report, University of New Orleans professor Ryan Gray sent a letter to the Corps detailing a list of ways that Gulf South’s methodology for locating unknown cemetery sites was “completely inadequate.”

Gray, who worked for eight years for a private cultural resource management firm in Louisiana before he got a doctorate in archaeology at the University of Chicago, concluded that the Willow Grove Cemetery likely extends beyond what is visible. The land around it, he wrote, is “almost positively the location” of “unmarked enslaved or nineteenth-century post-Emancipation burials.”

Greenfield did not respond to questions about potential burial sites, but on its website the company says it “has gone above and beyond what is required to ensure there are no ancestral burial grounds where the facility will be located.”

Cultural resource management firms have been criticized before for missing historic sites in their reports. Just up the river several years ago, a firm hired by a petrochemical company initially failed to document burial sites that activists and researchers uncovered by comparing aerial photos from the 1940s that might still have shown the contours of those plots with 19th-century maps that identified locations of cemeteries. After an outside archaeologist alerted the state to the likely existence of gravesites, the petrochemical company that owned the land agreed to cordon off at least one of those cemeteries.

In December 2020, Gulf South submitted a first report to the state historic preservation officer. After reviewing the work, the state asked the company to expand the radius of its study, to include all of the Whitney and Evergreen plantations and the communities nearby and to take into account other potential impacts. This is the work Edwards and another employee were assigned to.

Edwards said she raised the issue of unknown graves in the hopes it would spur the Division of Historic Preservation to demand that Greenfield conduct a more diligent search for unmarked burial sites, including near the Willow Grove Cemetery. (Edwards’ co-author has recently taken a job as a compliance officer with the Louisiana Division of Archaeology, overseeing cultural resource management reports. She declined to be interviewed because she is not authorized by the state to speak to the press.)

“If there might be burials,” Edwards said, “why not look harder?”

Last year, the Whitney Plantation Museum, which decades ago was added to the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places, put up a new plaque on the museum premises. “It is a major threat to the slave-decsendant community in Wallace,” the plaque reads, referring to Greenfield’s plans. Visitors see the display before they reach a memorial to men who were executed after staging the German Coast uprising, the largest revolt of enslaved people before the Civil War.

“This grain elevator would take up hundreds of acres of the fields around you that once formed Whitney Plantation, potentially destroying unknown burial sites,” the plaque says. “It will contribute to the existing toxic burden with the grain dust pollution, and permanently change the landscape of West St. John Parish.”

The grain elevator would be visible from parts of the plantation memorial site. And it would tower over a small restaurant on a verdant, tree-shaded plot off River Road.

Joy and Jo Banner, twin sisters in their mid-40s from Wallace, run the restaurant, which is on the same road as their family home. They also are the co-founders of the Descendants Project, a nonprofit dedicated to lifting the history of Black people in the region, and in particular ancestors of enslaved people in the river parish plantations.

After both sisters left Wallace for college and graduate school, and in Joy’s case to get a doctorate and then teach at a university in Texas, they returned to work in this small community. Like many residents, they trace their ancestry to people who were enslaved in these very plantations, including Whitney.

The Banner sisters have dedicated much of their time to building the Descendants Project so that people like Grows might gain some power in decisions about how their communities change. For the last year, that has meant fighting Greenfield’s plans. Along with other advocates, they’ve alleged that the industrial facility will lead to the kind of harm that Edwards was independently documenting, entirely unbeknownst to them, because the report as she wrote it has never been released.

“If they build this, this community will not survive,” said Joy Banner, whose day job is communications director of the Whitney Plantation Museum.

In May of 2021, the Banner sisters heard reverberating bangs originating several hundred feet from their home, on the land that Greenfield owned where the elevator would be. Builders were driving large metal beams, more than 20 of them, into the ground to determine feasibility for building, according to Greenfield. “If you didn’t know what was going on, you would think that there’s nothing you can do to stop it,” Jo Banner said, pointing into the field, just past their family home, where Greenfield placed a “No Trespassing Private Property” sign.

After the beams were pounded into the ground, lawyers with the Center for Constitutional Rights who represent the Descendants Project sent a letter to the Louisiana attorney general and the Louisiana Division of Archaeology, requesting that they force the activity to stop.

The letter cited work by a research firm called Forensic Architecture, based at Goldsmiths’ College at the University of London, that had been investigating the location of historic cemeteries in Cancer Alley, the predominantly African American region between Baton Rouge and New Orleans that’s packed with dozens of petrochemical plants and refineries. Using historic maps and aerial photographs, they’ve identified geological anomalies that could indicate burial sites, including trees growing in otherwise-cultivated fields. In some cases, those anomalies took root because plows or planters had long steered clear of known or suspected locations of graves.

“If you are genuinely interested in finding antebellum or other historic sites, you want to find the earliest possible view of the land,” said Imani Jaqueline Brown, the researcher with Forensic Architecture who spent a year studying the geography, architecture and cartography of the region and constructed the maps of the anomalies in Wallace. Brown said two sites are particularly likely to be burial places, based on their relative location to plantation architecture.

Gulf South said that it “did review historic maps and aerial imagery and considered the potential for burial locations” and “found no evidence of potential burial locations within the footprint of potential ground disturbance resulting from the project.”

The attorney general’s office replied to the letter from the Descendants Projects’ lawyers. “While some of the anomalies identified in your letter may represent unmarked burial sites,” it said, “so long as they are undisturbed we cannot take action under the existing laws.” Unless bones were dug up, in other words, under Louisiana’s cemetery laws, the state could not stop the work.

Another group of lawyers, also working with the Descendants Project, was trying to stop the federal permit, arguing in part that grain dust could leak into the air and create a respiratory irritant.

Greenfield disputes that the grain elevator would cause such problems, adding that “it will be one of the safest and cleanest facilities in North America. Greenfield is engineered to outperform all current and anticipated EPA standards.”

In November, the Descendants Project sued St. John the Baptist Parish to try to stop the project. Through their lawyers in that suit, the group presented evidence that the grain elevator land had been zoned for industrial use through fraud; a corrupt land deal three decades earlier landed the former parish president in federal prison. A judge in late April ruled that the case could proceed. Greenfield, which the court allowed to become a party to the case, said it would likely appeal. In court filings it has argued that the 30-year-old zoning decisions, whatever their origins, were approved by the St. John Parish Council.

Among the claims in the suit, the Descendants Project says that the sprawling operation could pose a risk to their own ancestors’ graves. The sisters aim to preserve the land to serve Black communities who have lived here for hundreds of years yet have been robbed of their claim to it by those who controlled it.

“These are Black spaces,” Joy Banner said, sitting on the lawn of her restaurant, about the geography of the plantations amid which she lives. “The trauma of not being able to talk freely about our own history is hurting our communities.”

Jo Banner added: “We have this district, we have an area that is really not found anywhere in the country. Communities like ours have been surviving all this time, since slavery and after slavery, so we’re fighting to protect this place.”

It is impossible to know how often important sites get covered up or downplayed in cultural resource management reports. These omissions typically come to light only because someone insists on revealing them.

After Edwards quit her job at Gulf South, she felt compelled to tell the state what had happened. On Oct. 22, 2021, she emailed the director of the Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation, stating that the report she had drafted, and a set of accompanying forms, are “very different from the current version that should be coming to you soon.”

“The current version of the report was written by the project manager and the client, playing architectural historian, and they have made eligibility determinations and conclusions in the report that I absolutely do not agree with,” she wrote in an email ProPublica obtained. “Since my professional reputation in Louisiana is involved in this, I wanted to ask you to please be aware that my name, my degree, and SOI [Secretary of Interior] qualifications should not [be] associated with this revised report in any way.”

“That elevator was going to be harmful,” Edwards told ProPublica. “That is what I concluded.”

For communities with an interest in the land, removing those kinds of conclusions can foreclose access to a provision of federal law that promises communities a say in what happens when historic sites are at risk. For land that Black communities are deeply connected to but have never been allowed to control, like the land in Wallace, community consultation provides a rare opening, however narrow, to be heard.

“Consultation opens a crack to holding the laws to an ethical standard,” Gray, the University of New Orleans professor, said.

Historic preservation has given preference to the protection of grand things, places like slaveowners’ homes and courthouses and stately cemeteries, sites controlled by and for white men of significance and maintained with their wealth and by white-led institutions. Places whose significance is tied to how enslaved people and their descendants lived and died rarely have been recognized by protection laws. Only a tiny fraction of the 90,000 sites on the National Register of Historic Places are specifically associated with Black people.

Community input allows for “those preservation laws to be applied in a more equitable way,” Gray said, “to understand integrity differently.”

After Edwards sent her email to the director of the state Division of Historic Preservation, warning the agency that it was about to receive a gutted report about the Greenfield grain elevator, the director, Nicole Hobson-Morris, replied: “You have my respect for standing up for your professional reputation.” Edwards, who now works for a national environmental compliance firm, said she heard nothing more from the state. She thought that was the end of it.

But Hobson-Morris later raised flags about the project. On Jan. 20, 2022, in an email to the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources, which oversees a separate state permitting process, she wrote that her office “has concerns regarding cumulative impacts the Greenfield project may present to historic and cultural resources in the area. We believe environmental and audible impacts over time may adversely affect historic resources in close proximity to the project.” She noted that when the Army Corps of Engineers reaches out to the state as part of its review, she will be communicating these concerns.

On April 12, the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, in its effort to halt the permits, filed comments and a set of attachments to the Corps. Among them was the email that Edwards had written to the state.

“The Corps must not allow Greenfield to develop the proposed Wallace site in light of the unreliability of the applicant’s report on the cultural, historical, and archaeological resources at and near the site,” the clinic wrote.

The Corps confirmed that it had received the email that Edwards wrote and had seen the revised report from Gulf South. The agency told ProPublica it disagreed with the report’s conclusion that the Greenfield development would inflict no negative impact. The Corps said it would enter a process to develop a plan to protect sites of historic significance.

Six days after submission, the Tulane clinic received notice from the Corps. The Descendants Project had been named a consulting party in the Greenfield permitting process. “It feels like a shift. We’ve been fighting against heavy industry, and for a voice about this land, for so long,” Joy Banner said. “We’ve been able to gather enough strength where they’re forced to listen to us, to take us into account.”

“We at the Corps are seeing adverse impacts,” said Ricky Boyett, the head of public affairs for the group in New Orleans. The Corps, he explained, will work with the National Park Service, since the Evergreen Plantation is an official national historic landmark, and with other stakeholders, including the Descendants Project, to develop an agreement about how the project might proceed and how to protect sites of historic significance.

“There’s discussion of cemeteries in the area,” Boyett added. “We need to do a little more research on those as well.”

The permit for the grain elevator, he said, is still under review.