The number of youth detained in Wisconsin’s youth justice system dropped by as much as 33 percent in the early days of the pandemic due to a number of alternative measures, and the people working in the system want to make those changes permanent, a study has found.

The number of youth detained in Wisconsin’s youth justice system dropped by as much as 33 percent in the early days of the pandemic due to a number of alternative measures, and the people working in the system want to make those changes permanent, a study has found.

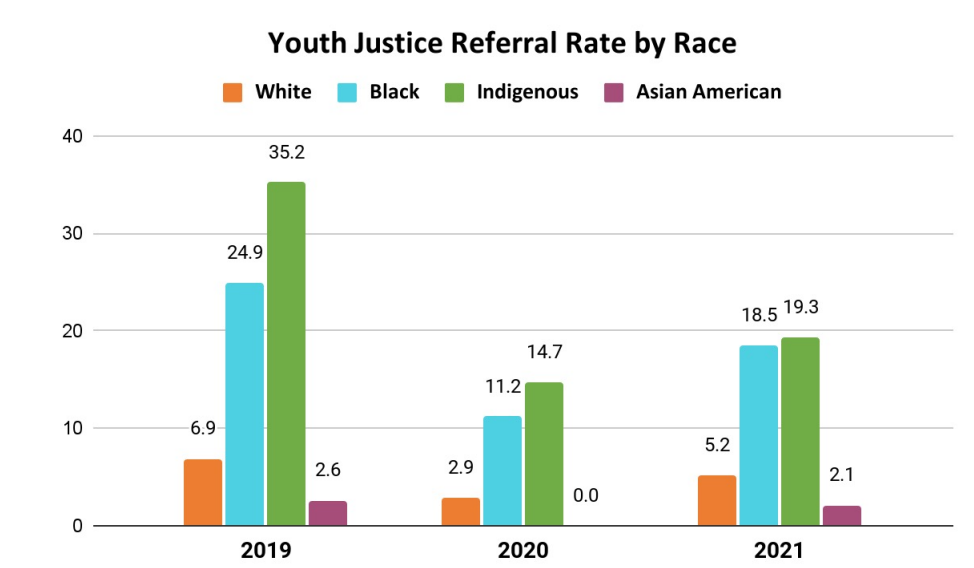

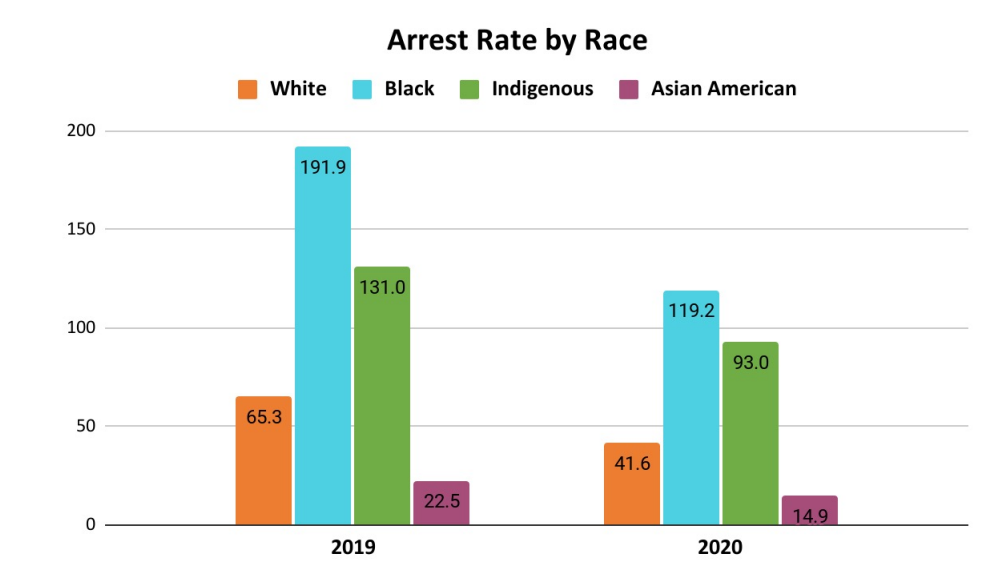

The study, initially done in January 2021 and updated in February 2022, also found that even as the number of children incarcerated fell, racial disparities remained consistent.

“The system started operating differently, because it had to under those emergency circumstances,” said Erica Nelson, advocacy director for Kids Forward, the agency that conducted the study.

Nelson said recognition that the dangers of COVID-19 in detention facilities caused the youth justice system to sharply decrease the number of youth referred into the system to begin with, and detain only those who posed an immediate threat to themselves or others.

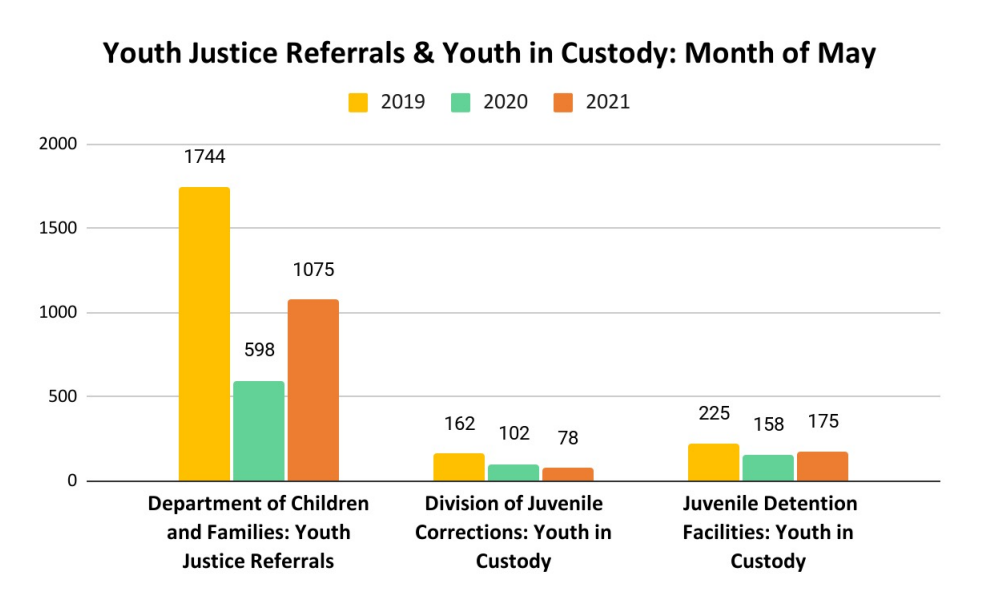

The number of referrals to the youth justice system fell from 1,744 in May 2019 to 598 in May 2020, a decrease if 66 percent, and rose to 1,075 in 2021 — still 38 percent lower than 2019 levels. Meawhile, the number of youth in state or county custody fell from 387 in May 2019 to 260 in May 2020 — a 33 percent decline — and fell again to 253 in May 2021.

“The big takeaway was, look what’s possible. Look at what happened without new funding, without new legislation, without new anything,” Nelson said. “In the moment, people within the system were finding alternatives (to arrest and incarceration).”

Fewer youth in custody is a good thing, Nelson said.

“Even one night in detention can have a long standing impact on how they perceive themselves and their rate of recidivism,” she said. “So many youth that enter the system or interact with the system actually need support and services in other aspects of their lives. And that’s where we need to direct our efforts. … The answer to kids and families and communities under stress is not detention or incarceration.”

Kids Forward surveyed dozens of people who work in the system — social workers, attorneys, administrators, and so on — almost all of whom saw better outcomes in a system with far fewer youth entering the system.

Some of those survey also speculated that the sharp decline in referrals from 2019 to 2020 might have something to do with kids being home rather than at school.

“If arrests are way down because kids aren’t in school, the next question is how many kids are we arresting in school? And why?” Nelson said.

Disparities remain

Though the overall number of children entering the system has fallen, Black, Indigenous and Latino youth are still more likely to be referred or detained, the study found.

Nelson said many youth were offered alternatives to referral or detention, but those were not offered at the same rate to all.

“Why are these alternatives being either offered to or being taken greater advantage of by seemingly white kids, and then not the same for black and brown kids?” she asked.

Further, when the criteria for detention shifted to incarcerate only those who were a threat to the community, the criteria may not have been applied equally.

“There’s no question that the way the system has functioned within structural and systemic racism, as well as implicit biases, that the outcome is often that BIPOC youth, Black and brown youth, are perceived as being more dangerous,” she said.

A positive: virtual visits

Nelson said a second major finding — and a surprising one — was that the use of virtual video technology improved the experience of youth in detention and could create better outcomes, because it allowed for more regular contact with family members who may have a hard time visiting a detention facility regularly.

“Virtual appointments of any kind remove barriers to interaction and connection,” Nelson said. “Barriers such as transportation or the need for childcare or scheduling around work conflicts, which are barriers for people showing up in court or going to visit their kids.”

She also noted that virtual visits can create a more meaningful connection for incarcerated youth.

“I don’t think it would have occurred to many people at all to be like, ‘Oh, look, the youth gets to, look at home and see his dog … or wave to a sibling in the background,’” she said. “And it didn’t really enter the conversation. There’s little things that are huge, that we think are little things that end up to be really big and important.”

A permanent change?

The fact that referrals and detentions didn’t redound to 2019 levels in 2021, along with sentiments expressed in surveys of the people running the youth justice system, gives Nelson hope that the use of alternative diversions could be permanent.

“I think that people within the system want to make these things permanent. I think they see the value in them. They want to increase it, they want to scale it up, they want to continue to do it, they don’t want it to be a moment in time. … We can capitalize, we can learn, we can make a better system, and we’ve shown that we can do it. And we just need to do the hard work to do it, as opposed to just reverting to the way things were because the way things were was not working either,” Nelson said. “I think we can implement much of what we’ve learned as permanent and still maintain community safety, while simultaneously better serving the needs of youth to become thriving adults in our community.”

Nelson said that marks a slow but steady shift in the philosophy of youth justice.

Going back to the last cenury, the system was built around “the philosophy around detention of youth or even adults is either a deterrent, or from the perspective of punishment, as opposed to the perspective of rehabilitation,” she said. “Those are two different perspectives, I think that we really need to continue to move closer, with every passing day, to the perspective that the system’s role, especially when it comes to youth justice, should be one that’s rehabilitative, but even more so preventative.”

But even if those reforms become permanent, deep racial disparities would remain. To that end, the study recommends the creation of a “bipartisan, interdisciplinary, inter-agency study committee” to rewrite Wisconsin’s juveline justice code “using racial equity and trauma-informed frameworks.”

The study also recommends further examination of the data around the drop in youth justice referrals and formation of a committee to examine funding strategies to “ensure community-based social services for all youth.”

Lasting Impacts is funded by a grant from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. The best way to protect yourself and your community from COVID-19 is to get vaccinated and stay current on boosters. Click here for more infomation.