By Matthew DeFour, Wisconsin Watch

It’s Election Day 2022 in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and voters in this majority-blue city once again have no chance of electing a Democrat to legislative office.

That wasn’t always the case. New Deal Democrats, running in the wake of a bitter Kohler Co. strike, held the local Senate seat in the 1930s and again from 1983 until 2003. They also held an Assembly seat concentrated on the city in all but four years between 1959 and 2011.

But during the 2011 decennial redistricting process, Republicans split Sheboygan between two Assembly seats, each with more voters from majority red Sheboygan and Manitowoc counties. It’s one of many examples of how Republicans carved Wisconsin’s district boundaries to secure an invincible majority in a politically evenly divided state.

“With the splitting of the city with gerrymandering, that’s the big kicker,” said Calvin Potter, a former longtime Democratic state lawmaker who was Gov. Tony Evers’ high school civics teacher in Plymouth. “It took a city that in the early decades … voted 62% Democrat (and) made two districts in this county — both 57% Republican.”

When Republicans redrew the lines again in 2021, they further boosted their advantage in the Assembly. Compared with nearly 1,000 statehouse elections across the country between 1972 and 2020, Wisconsin’s efficiency gap in 2018 ranked as the fourth most skewed toward Republicans at 15.4%, according to researchers at Harvard and George Washington universities. Wisconsin’s 2022 results were even more skewed at 16.6%, a Wisconsin Watch analysis shows.

For relief, Democrats are looking to elect a liberal justice in April to the Wisconsin Supreme Court — which has final say over statehouse redistricting disputes. There’s no guarantee new maps would allow Democrats to win a legislative majority, but they might reverse a general trend of less competitive elections.

Democrats fighting uphill battle

Despite the built-in disadvantage, there’s still some fight left among the Democratic organizers keeping the squash soup warm at the Sheboygan County Democratic Party headquarters on Election Day.

As the 2022 midterm election approached, volunteers came by every day to pick up packets of voter lists and candidate postcards as they ventured out to knock on doors, even during a recent Packers game, said Mary Lynne Donohue, a former Assembly candidate and a plaintiff in a lawsuit that unsuccessfully challenged the 2011 maps as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander before the U.S. Supreme Court.

When a regular stops in to report that a church serving as a polling place down the street is displaying a “vote to save your religious freedom” message on its electronic marquee — a possible breach of rules banning electioneering at polling places — Donohue talks to the city clerk to ensure neutrality is restored.

Despite all the effort, local Democrats have only one candidate for the Legislature on the ballot.

Lisa Salgado, a medical assistant of 30 years, challenged Republican incumbent Rep. Terry Katsma, a retired community banker who previously served on the village board in Oostburg, a Dutch farming community about 12 miles south of Sheboygan.

“It becomes very difficult to recruit candidates when we know we’re going to lose,” Donohue said.

In fact, most races in the state are foregone conclusions with just four of the 99 Assembly races in 2022 decided by less than 5 points.

Having local candidates is still important to help the top-ticket candidates, Donohue said. Gov. Tony Evers, on his way to winning re-election by 3 points statewide, ended up losing Sheboygan County by nearly 16 points, but won the city itself by 11 points.

On Election Day, Donohue predicts Salgado might get 43% of the vote — which, she adds, would be a sign Democrats are staging a comeback. Still, Donohue admits, it’s deflating to put all this effort into an ill-fated campaign.

Salgado ultimately received only 37% of the vote.

“It just verifies for me that gerrymandering is a highly effective way of destroying democracy,” Donohue said.

One of the biggest skews gets bigger

Sheboygan is in some ways a microcosm of what has happened to Wisconsin over the past decade: Republicans run the Legislature from safe rural districts while Democrats, packed into the state’s largest cities, have no ability to enact legislation their constituents support.

Sheboygan Mayor Ryan Sorenson, a former Democratic Party 6th Congressional District chair, said urban voters are only in recent years becoming aware of the effect the lack of representation has had on the city’s ability to advocate for issues that matter to them, such as affordable housing, water quality infrastructure and education, particularly in a school district where students of color are now a majority.

“It’s very watered down and so we don’t necessarily have an advocate that is fully aware of all the city issues that we have,” Sorenson said. “Anecdotally, I think people feel more deflated because they’re like ‘Well it’s gerrymandered, so what are we going to do anyway?’ ”

Gerrymandering refers to the centuries-old practice of lawmakers redrawing legislative boundaries after each U.S. Census to advantage themselves and their own party and disadvantage the other side. Both Republicans and Democrats do it, although some states have assigned the task of mapmaking to nonpartisan commissions.

After the 2011 redistricting, in which Republicans controlled the Legislature and governor’s office, the Wisconsin Assembly maps became the most skewed toward Republicans in the country over the next five elections, and second most skewed behind Rhode Island, which was skewed toward Democrats, according to research compiled by Chris Warshaw, an associate professor of political science at George Washington University.

In the latest round of redistricting, in which rulings from the conservative state and U.S. supreme courts allowed Republican legislative maps to prevail over objections from Democratic Gov. Tony Evers, Wisconsin’s Assembly skew only got worse.

That’s according to the “efficiency gap,” one of the measurements political scientists have developed to illustrate partisan gerrymandering. The efficiency gap measures how many votes are “wasted” — having no chance to affect the outcome — when one party’s voters are either packed into lopsided districts (Think of Dane County where almost 80% voted for Evers), while others are broken up, or cracked, into districts where the margins are closer, but the party drawing the maps is almost guaranteed to win.

One way to illustrate what packing and cracking in Wisconsin looks like: In the 10 closest Assembly races that Republicans won this year, the average margin was 7.5 points. In the 10 closest for Democrats it was 15.2 points. Wisconsin Watch didn’t analyze the Senate, where Republicans will control 21 of 33 seats with one vacancy in January, because only half of the seats were up for election this year with the rest up in 2024.

The Wisconsin Assembly’s efficiency gap under the 2011 maps was 11%, according to PlanScore, a nonprofit that tracks district fairness, where Warshaw is one of the principals.

PlanScore has yet to rate the 2022 results. But using the efficiency gap formula provided by Warshaw and the 2022 vote totals, Wisconsin Watch estimated the latest Assembly election results had an efficiency gap of about 17% favoring Republicans.

While the numbers can be useful to compare states, they essentially confirm an obvious problem: Wisconsin is nearly evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans — Evers won 51% to 48% — yet Republicans control nearly two-thirds of the legislative seats.

“This is not normal,” Warshaw said. “In all of American history we don’t observe many cases like this. … This is way out in the tail of any kind of distribution of how democracy is supposed to work.”

Latest maps show more gerrymandering

When Republicans drew the maps in 2011, they spent hours working under secretive conditions tweaking each iteration of the map to ensure a majority that could withstand even a Democratic wave year. Sheboygan is one example where dividing a city helped produce an extra Republican seat.

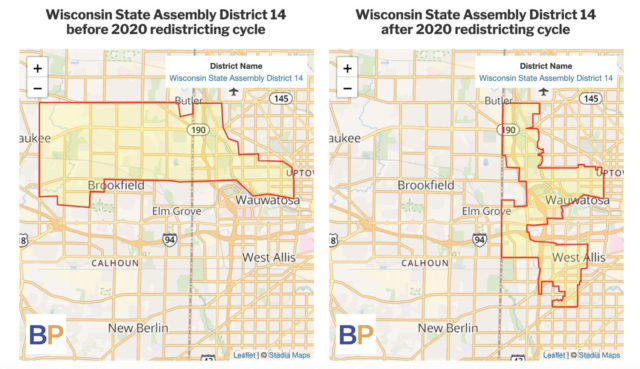

Another was in the Milwaukee suburbs, where Republicans drew two districts in 2011 that cut in half both conservative Brookfield and increasingly liberal Wauwatosa to hold both the 13th and 14th districts. Despite that, by 2020, Democrats had won both seats.

But gerrymandering isn’t always divide and conquer; this time around there was some retreat and retrench. The latest maps created a Republican 13th District centered on conservative Brookfield and a Democratic 14th District focused on Wauwatosa. A Republican newcomer won the 13th by 13 points, and the Democratic incumbent won the 14th by 27 points.

In the latest redistricting, Republicans also drew another seat in the district that includes Superior in far northwestern Wisconsin, which, like Sheboygan, will no longer have Democratic representation in the Legislature.

Marquette Law School research fellow John Johnson calculated the 73rd Assembly District moved 3 points in favor of Republicans after the 2021 redistricting. In fact, Republican Angie Sapik — who had deleted her Twitter history in which she had denied the 2020 election results, supported the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection and denounced the Republican Party — defeated Democrat Laura Gapske by 2 points in what was one of the most bitter battles in the state.

Both sides poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into the race as outside groups attacked Gapske’s vote on the Superior School Board supporting a fifth grade human growth and development curriculum that explained how a person’s sex and gender can differ.

Republicans made the district more friendly by adding more of conservative Burnett County to the 73rd, effectively doing to Superior’s Democratic voters what they did to Sheboygan’s Democrats in 2011.

“The intention of the Republican map drawers up there was really obvious,” Johnson said. “They were trying to tilt the districts to Republicans.”

GOP blames Dems

Republicans deny they skewed the maps, and instead blame Democrats for packing themselves into cities and candidates who don’t appeal to outstate voters.

Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu, R-Oostburg, and Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, declined interview requests. They said at a recent WisPolitics luncheon that Democrats should have been able to win some of the closely contested races in the state, but their views have alienated rural voters.

“Republicans won because I think we had better candidates, better organization and a better message,” Vos said.

University of Wisconsin-Madison political science professor Ken Mayer examined the geographic phenomenon and found the bunching of Democrats in cities accounted for a 2- to 3-point Republican advantage — nowhere near the actual advantage the party currently enjoys.

“There will be people who deny it to you with a straight face, but there is no empirical doubt that this remains the most gerrymandered state in the country,” Mayer told Wisconsin Watch.

But it’s not just gerrymandering. Democrats are less likely than Republicans to vote in races that aren’t at the top of the ballot, a phenomenon known as “roll-off,” said Gaby Goldstein, co-founder of the liberal Sister District Project.

In Wisconsin, Evers got more votes than Democrats in 73 out of 83 Assembly districts where they fielded a candidate, a Wisconsin Watch analysis finds. By contrast, his Republican opponent Tim Michels got more votes than the Republican Assembly candidate in only four of the 89 Assembly districts where they fielded a candidate.

“Republicans have invested generously over generations in building not just infrastructure, but narrative, political ideology that centers state power in a way that is emotionally resonant to voters,” Goldstein told Wisconsin Watch. Her organization is urging Democrats, who she said have historically focused on federal power building, to focus more on state politics.

Another factor that could be hurting Democrats is that gerrymandering can have a cumulative negative effect on the party out of power, according to research by Warshaw and Harvard Law School professor Nicholas Stephanopolous.

“When a districting plan is biased against a party, its candidates contest fewer legislative seats and have worse credentials when they do run, its donors contribute less money, and its voters are not as supportive at the polls,” they concluded.

‘Democracy is not real’

That’s how Assembly Minority Leader Greta Neubauer, D-Racine, sees it. In an interview, Neubauer said gerrymandering has created “a self-reinforcing cycle” in which candidate recruitment and civic engagement are diminished. The result, she said, is that “democracy is not real when it comes to the Legislature in Wisconsin.”

“Republicans right now are insulated from the will of the people,” she said. “Republicans have been able to starve local governments of resources and escape consequences for that because of gerrymandering.”

Neubauer noted that the GOP-run Legislature heard only 2% of Democrat-authored bills in the past session. “They refuse to act on many policies that have widespread support in Wisconsin,” she said, “because they don’t want Gov. Evers to be seen as successful.”

Polling suggests there is majority support in Wisconsin for some of those measures, including legalizing marijuana and abortion in most cases, accepting federal Medicaid expansion funding, requiring criminal background checks for private gun sales and — notably — switching to nonpartisan redistricting.

A majority of both Democrats and Republicans support nonpartisan redistricting, according to a recent poll conducted by UW-Madison communications professor Mike Wagner. Support ranged from 51% among suburban Republicans to 70% among urban Democrats. Among rural Republicans, who likely benefit the most from the current maps, 54% support nonpartisan redistricting, the late October poll of 3,064 Wisconsinites found.

Less competitive districts

The late Bill Kraus, a Republican and longtime advocate for transparent government and bipartisan compromise who led Common Cause in Wisconsin for 20 years, lamented in a June 2004 blog post the “widespread megalomania that is the undesirable byproduct of representing a safe district.” He noted there were only about 10 “even remotely competitive” seats in the Legislature.

That year, there were just 15 Assembly races within a 10-point margin. In the next three election cycles the average was 22. After the 2011 redistricting, the average in the next five cycles dropped to 11. This year there were only eight Assembly races within that margin.

Kraus advocated for “something dramatic” to be done to address the problem and suggested redistricting be conducted by “dispassionate, disinterested outsiders.”

Since 2011, 56 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties have either passed a county board resolution or ballot referendum endorsing nonpartisan maps, according to a tally by the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign.

Nonpartisan maps don’t necessarily advantage one party over the other — unless one party has more voters — nor does it ensure competition. In Iowa, maps are drawn by a nonpartisan state agency, yielding legislative maps in the last decade with an efficiency gap less than 4%.

But Republicans won all four congressional districts and expanded their majorities in the state House and Senate, where they now have their largest majority since 1980. Of the 100 House races, 44 were uncontested.

No initiatives, binding referenda in Wisconsin

In Michigan, by contrast, Democrats took control of the state Legislature for the first time in 40 years, winning a 56-54 majority in the House and a 20-18 majority in the Senate.

Michigan’s Democratic wins came after a public ballot initiative in 2018 with 61% support created an independent redistricting commission following two decades of Republican gerrymandering. The maps created by that commission were in place for the first time this year.

The campaign to change Michigan’s system cost $15 million to collect 428,000 signatures and defend against Republican challenges before the state Supreme Court, said Nancy Wang, executive director of Voters Not Politicians, which organized the effort.

The major catalyst, Wang said, was the Flint water crisis, in which the city started pumping lead-tainted drinking water from the Flint River to save money while state-appointed emergency managers were in charge. Republicans expanded the emergency manager powers in 2011 and voters repealed it in 2012, but Republicans passed a different version in 2013.

Wisconsin doesn’t provide the public with the option to change state law through a ballot initiative, which Wang said makes it difficult to know how to solve the gerrymandering problem.

“It’s a really tough question,” Wang told Wisconsin Watch. “Ordinarily, what you would do as a voter to demand change is you would lobby and threaten to oust your politicians if they didn’t listen to you. Well, if they’re insulated from any kind of repercussions, then what power do you have?”

Her suggestion: Continue to agitate and educate voters to the point where they demand change in such numbers that they overcome the political advantage that politicians have from gerrymandering.

A court solution?

Democrats are eyeing the April 4 Wisconsin Supreme Court election as an opportunity to win a majority that might toss out the new legislative maps.

Candidates so far include conservative former Justice Daniel Kelly, Dane County Circuit Judge Everett Mitchell, Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Janet Protasiewicz and Waukesha County Chief Judge Jennifer Dorow, who presided over the recent trial of the Waukesha Christmas parade killer. The winner will replace retiring conservative Justice Patience Roggensack.

Should a liberal candidate win in April, Democrats would likely wait until the new justice was seated in August before bringing a case. That would leave little time before the 2024 election.

Doug Poland, a lawyer who represented plaintiffs in challenges to the 2011 maps, noted there’s already a robust case file on gerrymandering in the federal court system.

In Gill v. Whitford, the case that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, a three-judge federal panel found the 2011 maps were “an unconstitutional political gerrymander.” The panel noted the lopsided margin for Republicans was “not explained by the political geography of Wisconsin nor is it justified by a legitimate state interest.”

The U.S. Supreme Court later ruled the federal courts do not have a role to play in settling disputes over political gerrymandering. But that left open the ability of state courts to intervene.

“There is already a robust holding of law out there that partisan gerrymandering violates the constitution,” Poland told Wisconsin Watch. “It would be wholly disingenuous of any state supreme court considering this issue to look at those decisions and say, ‘We disagree with you.’ ”

Republicans would likely counter that the Wisconsin Supreme Court has already settled the mapping dispute. Honoring court precedent, a legal doctrine known as stare decisis, is something even liberal justices have defended, said Misha Tseytlin, the state’s former Republican-appointed solicitor general, who argued in favor of the maps in the Gill case.

Even if Democrats were to successfully challenge the maps as a partisan gerrymander, they would still have to come up with a way to know where to draw the line on what constitutes a partisan gerrymander. Some have suggested prohibiting maps with an efficiency gap above 8%. However, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts referred to that measuring stick as “sociological gobbledygook.”

Tseytlin noted in New York, where partisan gerrymandering was rejected by a court and a special master drew new district boundaries, Democrats won the governor’s race by 6 points, but are expected to retain a supermajority in the state Legislature. A major reason for that, he said, was the power of incumbency.

“There are dynamics that often account for why incumbent state legislators win, regardless of the map,” Tseytlin said. “Because incumbents have a strong advantage.”

An alternative way to elect representatives

Nonpartisan mapmakers could be instructed to keep communities of interest intact, something that has broader civic benefits, according to a 2013 study by College of New Jersey political science professor Daniel Bowen.

Not only are constituents more likely to be ideologically similar to their representatives, they’re more likely to contact their representative, be satisfied with that contact, recall their representative’s work benefiting the district and know basic information about their representative. Independents and members of the opposite party also reported positive outcomes in districts that kept municipalities together.

“At the most basic level, a legitimate districting system must fairly convert votes into seats,” Bowen told Wisconsin Watch. “Wisconsin is a prime example for how clever mapmakers can adhere to some traditional districting principles … while producing extreme maps that favor one political party. That is a major problem that threatens the legitimacy of democratic governance in Wisconsin and is especially noticeable in a state with such highly competitive elections.”

But even within communities there are voters with different views and interests. One way to keep more of them engaged could be new legislative configurations and voting systems that have been tried in some European countries, said Mark Copelovitch, a political science professor at the La Follette School of Public Affairs at UW-Madison who has studied alternative voting and redistricting models abroad.

For example, instead of single, winner-take-all districts, the state could set up multimember districts that could send two or more members of different parties to a legislative chamber, a system used in nine states.

Researchers at Cornell University concluded in a 2020 paper that the fairest and most geographically compact results are accomplished with three-person multimember districts combined with ranked-choice voting — in which voters rank candidates, with the one getting the most first-place votes winning. Surplus votes are transferred to voters’ next preferences.

Under such a system there’s a greater chance places like Democratic Milwaukee and Dane counties, which have the state’s second- and third-largest share of Republican voters behind Waukesha County, could send Republicans to the Legislature, Copelovitch said.

It might also allow Sheboygan to elect a Democrat to the Legislature again.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.