By JIMMY GOLEN, AP Sports Writer

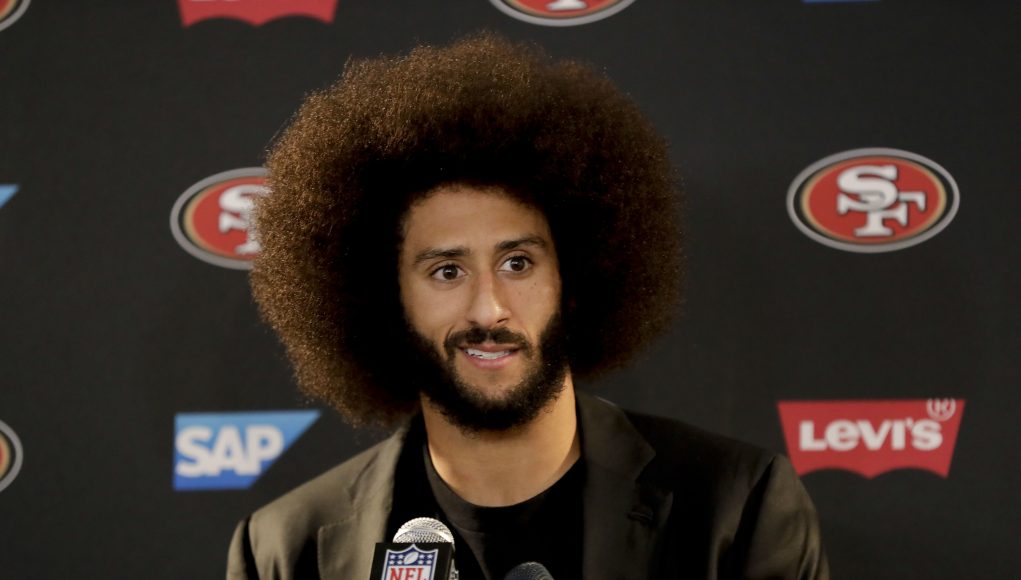

Let’s assume that Colin Kaepernick is better than several quarterbacks — backups, and even starters — who have managed to find jobs on NFL rosters this season.

(He is.)

And let’s also say that teams refused to sign Kaepernick not because he isn’t good enough, but because he decided to kneel during the national anthem to protest racial injustice in America.

(That, too.)

It still isn’t enough for the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback to win the grievance he filed against the NFL on Sunday. To prove collusion, Kaepernick will need hard evidence that owners worked together — rather than decided individually — to keep him out of the league.

“We come to the distinction between collusion and what each individual team does as a matter of its business interests,” said Alfred Yen, who teaches sports law at Boston College Law School.

“If it turns out that all (32) teams have it in their business interest to do the same thing, so be it,” he said. “After all, all teams have it in their interests not to employ me as their starting quarterback. And that’s OK.”

The grievance claims NFL owners — egged on by President Donald Trump — agreed to blackball Kaepernick from the league “in retaliation for (his) leadership and advocacy for equality and social justice and his bringing awareness to peculiar institutions still undermining racial equality in the United States.”

It calls the league’s behavior regarding Kaepernick “suspicious,” ”unusual” and “bizarre.”

But the seven-page document does not give any examples of how NFL owners worked together to keep him out.

And that’s precisely the challenge of any collusion case.

The league declined to comment on the grievance to The Associated Press on Monday except to refer to previous statements by Commissioner Roger Goodell in which he insisted that “there are 32 different decisions” made by individual teams.

“The things we are always about are meritocracy and opportunity,” he said in September. “I want to see everyone get an opportunity, including Colin. Those are decisions that are made by football people.”

Here are some other issues raised by Kaepernick’s grievance:

Q: How did we get here?

A: A second-round draft choice out of Nevada, Kaepernick took over as 49ers starter midway through the 2012 season and led San Francisco to the Super Bowl that year. The team returned to the NFC championship game the next season, but then sank in the standings. Since Thanksgiving of 2014, it has had four head coaches while winning eight of 44 games.

In 2016, Kaepernick began kneeling during the national anthem to protest the shootings of unarmed black men by police officers. After the season, he opted out of his contract with San Francisco and became a free agent. No other team was willing to sign him, even as Brian Hoyer, Scott Tolzien, Tom Savage, Mike Glennon and DeShone Kizer all found work as starters, only to be benched.

Q: So, does that prove collusion?

A: Not quite. The CBA says specifically that the decision not to sign a player — even if he’s better than an alternative — is not proof of collusion. Instead, there must be evidence of an agreement between one team and “the NFL or any other club” that influences an individual team’s decision making.

What’s more, Kaepernick will need to prove to a neutral arbitrator — University of Pennsylvania Law School Professor Stephen Burbank has served in the position since 2011 — by a “clear preponderance of the evidence” that collusion occurred. This is a higher standard than in a normal civil case, Yen said, but still short of the criminal burden of “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Q: Is there any precedent for what Kaepernick is claiming?

A: Before the practice was prohibited in collective bargaining agreements, teams routinely worked together to keep player salaries down. Another, more pernicious form of collusion was the “gentlemen’s agreement” among owners that banned black players from baseball until Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947.

In the 1980s, baseball owners were found guilty of colluding in three straight seasons to suppress salaries for a group of free agents that included future Hall of Famers Andre Dawson, Paul Molitor and Tim Raines. Teams claimed they were allowed to share information as long as they didn’t set artificial prices; an arbitrator disagreed and granted the players $280 million and “new-look” free agency.

Steroid-tainted slugger Barry Bonds was less successful when he claimed that teams blackballed him in 2008, the season after he broke Hank Aaron’s career home run record. Bonds said he would play for the major league minimum, and he offered statistics that showed he was worth much more. But baseball’s arbitrator said he needed hard evidence of teams working in concert.

Q: What if Kaepernick’s grievance fails?

A: Like Tom Brady before him, Kaepernick could go to federal court to argue that football’s arbitration system was fundamentally unfair. But Kaepernick faces two challenges that Brady didn’t in the drawn-out “Deflategate” scandal that ended with his four-game suspension being upheld.

First, Kaepernick has to deal with the precedent set in “Deflategate,” which declared unambiguously that the federal courts should not interfere in the NFL’s collectively bargained arbitration process.

Second, Kaepernick’s grievance will be heard by a neutral arbitrator instead of Commissioner Roger Goodell. While that gives him hope for a receptive audience, it also eliminates one of the key grounds for a potential appeal.

“It’s a different ballgame when you’re in front of somebody who can go either way,” Yen said. “If he doesn’t win in front of these folks, I wouldn’t fancy his chances in front of the federal courts.”

___

Jimmy Golen covers sports and the law for The Associated Press.