Sergio González, author of “Mexicans in Wisconsin,” is a University of Wisconsin alum and is just about to being his first year as a professor of history at Marquette University. He is a Wisconsin native raised in Milwaukee by two Mexican migrants. Sergio returned to Madison for his PHD in 2012 after teaching middle school at a dual-language immersion program. He’s also one of the most powerful Latinos in Wisconsin, according to Madison365’s Sí Se Puede 2018 list.

Sergio González, author of “Mexicans in Wisconsin,” is a University of Wisconsin alum and is just about to being his first year as a professor of history at Marquette University. He is a Wisconsin native raised in Milwaukee by two Mexican migrants. Sergio returned to Madison for his PHD in 2012 after teaching middle school at a dual-language immersion program. He’s also one of the most powerful Latinos in Wisconsin, according to Madison365’s Sí Se Puede 2018 list.

He stresses that Wisconsin historians have done a poor job telling the story of its Latino inhabitants, who have been involved in Wisconsin’s community for over a hundred years.

“I think there’s a certain political expediency in 2018 to better understand Latino communities that have in Wisconsin and then their struggle to find a sense of belonging in places like Milwaukee and Madison across the state,” he explains.

The first Mexican immigrant to arrive in Wisconsin, González says, was Raphael Baez in 1880. Recruited by C.D Hess Opera Company for his talent as a pianist, he went on to perform as a choir director and organist, performing in some of Milwaukee’s largest churches and synagogues. Baez became Marquette’s first Latino professor teaching music. González notes how this early example makes for a contrasting depiction of what people would come to expect out of a Latin person who migrated to Wisconsin.

“I find it interesting that the historical record of Latinos in Wisconsin begins a good 40 years before most people assume that Latinos were coming to the state,” González says. “Raphael Baez’s story really disrupts our understanding of Latino immigration to this date. It complicates it. It diversifies it.”

By 1920 the first sizeable wave of Mexicans, dubbed Los Primeros or “The First,” began to arrive in Wisconsin, working mostly in the agricultural industry. A slew of federal, international and local factors played into drawing this initial wave of Mexican workers to Wisconsin. At the federal level, the U.S government passed a series of immigration laws halting European immigration into the country, while enabling entry for people from Latin America.

Wisconsin tanners and foundries, largely located in Milwaukee but also scattered across the state, began sending recruiters to Latin America. In congruence with the U.S policy shift was a revolution in Mexico, resulting in an additional northward push of people trying to find safety from war.

Many Mexicans recruited by these companies had their time cut short in Wisconsin by the Great Depression. Many left the state or the country entirely. It was not until after World War II ended that the next sizable wave of Latinos, now mostly Tejanos — Mexican Americans from Texas — cane into Wisconsin.

González uses the term “First Hook” to label the recruiters’ place in establishing the Latin community in Wisconsin.

“Like any other group of migrant people, once people had success they told their family members and friends to follow and make a life for themselves as well,” González says.

The first sizeable group of Latin American people to blossom in Madison occurred during the 1950’s and 60’s, recruited by both the agricultural industry and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Throughout the 1950’s an average of 14,000 to 15,000 Mexican, Tejano and other Latin migrant workers traveled from Texas to Wisconsin every single year to plant sugar beets, snap peas, cherries and a variety of other crops in the area.

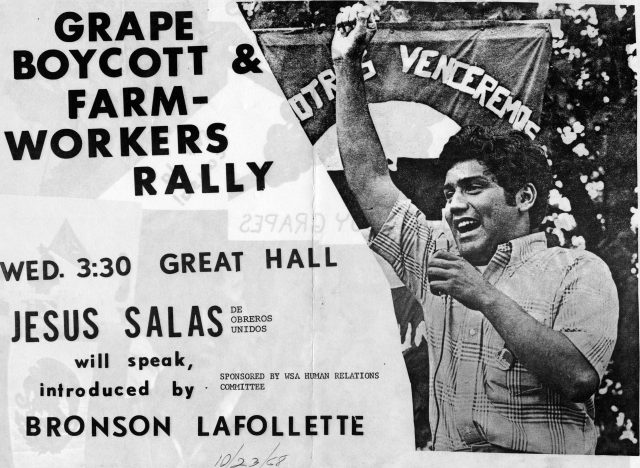

Groups such as the Obreros Unidos — Workers United — worked in tandem with the efforts most famously championed by Ceaser Chavez to unionize migrant farmers and achieve better working conditions and fairer pay. However, González recognizes, “The story of Wisconsin migrant farm workers organizing is a particular story. It’s it own story. It’s a story that’s in response to working in conditions in Wisconsin and it’s a story that responds to the decades-long history of Tejano migration to Wisconsin in search of agricultural labor. There’s a number of important figures that lead that story, I think most importantly Jesus Salas, whose family had been coming to Wisconsin from Texas for years.”

Jesus Salas was in his early 20s during the mid-1960’s when he championed better living and working conditions for Tejano farm workers. He rallied his fellow Tejano workers and played a central role in building a movement that made a mark on Wisconsin’s history.

Unfortunately, the Obrereos Unidos were short lived because of the companies they worked against were successful in shutting them down. It was at this point in 1960s and 70s that the shift away from the agricultural sector and into the industrial took place. Latinos were now moving into the more central parts of Madison and Milwaukee and building their own communities.

Coinciding with this shift was a new influx of Latino groups into the state such as Puerto Ricans and Central Americans. By the 1980s the most prominent growth came in the Mexican community. Soon thereafter, national trade policy sparked another influx.

“It really explodes in the 1990’s with a series of free trade agreements that are signed with Mexico which drastically makes it more difficult for Mexican farmers to work on their own land and makes it real expensive for them to farm their own land in Mexico,” González says.

With all of these different groups of Latinos having come at varying times and in different national political climates, González notes that these varying groups have very different experiences.

“I always emphasize that when I talk about Latinos, I’m not talking about a Latino culture or a Latino History,” he says. “We’re talking about many different heritages and cultures and histories. Each community that develops within Wisconsin’s borders throughout the 20th century develops its own footprint within the state. I think it’s important we recognize that we can’t use this monolithic term of Latino or even really Mexican descent to fully encompass the experiences of all of these people.”

However, a commonality that has existed for many Latinos in Wisconsin alongside their European counterparts is Catholicism. “In the 1920s, the Catholic Church was really the only place in Milwaukee where Mexican immigrants felt at home and just as importantly where they felt like they could build a sense of community with the white Milwaukeeans,” González says.

“(Churches) have also been spaces of contention,” too, he says. “You find examples in the 1960’s when Latinos demanded more resources from those religious institutions that purported to serve them and their families. In the 1980’s, you see Latinos from Central America finding a home within the church.”

This long history of Latino community-building in Wisconsin continues to spark contention, protest and hope.

Its (of) dramatic importance to see 20,000 Latinos and their allies take to the capital to the seat of power of our state to demand their equal place at the table,” González says of the “Day Without Latinos” protest that took place two years ago. “It’s also important to recognize that one of the reasons those bills (to further criminalize undocumented immigrants) were defeated was because the dairy industry would collapse (without immigrants).”

It’s natural to ask what González calls “the ‘so what’ question” — that is, why delve into the history of Latinos in Wisconsin?

In part, González says, it goes back to the fact that historians largely have not done a great job of documenting it, so it’s on us to make sure that history isn’t lost. But it’s larger than that, as well, for Latinos and other ethnicities alike living side by side today.

“We know that representation matters,” González says. “We know that understanding where a person comes from and placing them within this larger context and this history really matters. One of the reasons it matters is because if we don’t acknowledge the individuals who have lived here for years or that they have built institutions and senses of community, we tend to perhaps believe that they don’t deserve to be here in that case. The preservation of history, the telling of that history in many ways reminds us that Latinos have been a part of this state for 100 years and they will continue to be a part of the state for 100 years more.”