Madison Ballet’s 40th anniversary season closes this weekend and next with a program titled Turning Pointe, which, the company’s website says, “celebrates the company’s past, while it steps into a brilliant future.”

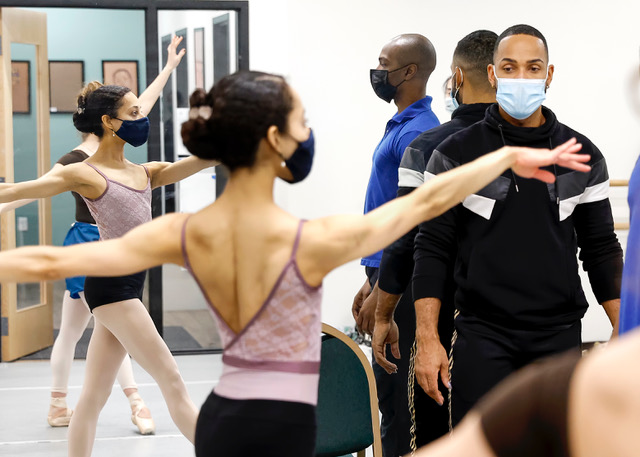

Leading the way into that future are two Black men: Jacob Ashley, who was named director of the company’s ballet school in January, and Ja’ Malik, the company’s incoming artistic director, who’ll take over for the outgoing Sarah Schumann, in July.

“It shows that we are present,” Ashley says of the historic hires. “It shows that we are part of this as well.”

The two men contrast in many ways; Ashley has been familiar to Madison audiences for 15 years, while Ja’ Malik had never set foot in Wisconsin before interviewing for this job. Ja ‘Malik started dancing at 4 or so; Ashley was a teenager before he took a ballet class. But both say they hope to build a more diverse company, broaden the audience’s horizons and create something truly special right here in Madison.

“An 80s Baby”

“I’m an 80s baby. I grew up enamored with Michael Jackson. He inspired a generation of dancers,” Ja’ Malik says. At just 3 or 4 years old, he memorized the entire dance sequence from the video of Jackson’s Thriller – and performed those now-iconic steps for everyone in the neighborhood. Regularly.

“I was doing them to the point where the neighbors and everyone was like, ‘please go take that child somewhere else. Let him learn some other dances so we can stop watching Thriller every day,’” he says. “Literally, I would do it every day. I was obsessed with it.”

At that age, dance became his means of communication.

“I was not a talker,” he says. “I could speak but I didn’t like to talk as a kid. I was probably 9, almost, when I really just would have a conversation with people. Before that, I would just try to avoid conversations at all costs. I just didn’t like talking. But I loved expressing myself through dance.”

So he joined a local dance school in Harlem, where he was usually the only boy. He enjoyed it and excelled, but never thought of dance as a career path – until he was 12 or 13 and went to Cleveland to visit an aunt, who took him to a performance of The Nutcracker with a Black lead.

“He was just everything that I could see in myself,” he says. “And so having that representation on stage and seeing that let me know, oh, this is more than just a fantasy of enjoying making up dances in your bedroom or dancing around the neighborhood. It was like, you can actually do this as a profession.”

After that, Ja’ Malik was all in.

“I literally went up to the director (of my school) and was like, ‘I want to be pushed. I need to learn how to do everything that he did on that stage,’” he says.

His teachers, all women, were very supporting and encouraging, but the school – and the art form – still didn’t seem to hold a future for him.

“I realized that ballet is wonderful and beautiful, and as much as I love it, it was still also very non-inclusive to me,” he says. “I didn’t really see a path forward other than Dance Theater of Harlem, which, there’s nothing wrong with that. But for me, I didn’t want to go to where everybody said, ‘Oh, well, you go to Harlem Dance Theater, because you’re Black.’ And I’m like, ‘No, I want to go where I want to go because I’m good.’”

And where he went was a performing arts high school in Cleveland, where he also studied on a full scholarship at a ballet school, and then back to New York to attend The New School as a member of the first cohort of students to earn BFA degrees through the university’s partnership with the Joffrey School. At the same time, he began studying with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, all while working at Starbucks. It made for very long days.

Soon he started to think about choreography as well, also inspired by witnessing a performance.

“I saw Ulysses Dove’s piece Urban Folk Dance at the Ailey company, and I was blown away,” he says. “I mean, I was sitting there in tears at what I was watching on stage, I was so moved by what he created. I was like, whatever it is that he did to create that, I want to do that.” After taking on a few small projects with peers and classmates, he staged a piece called “The Hour Before,” which earned him positive reviews and prompted New York Magazine to call him “a choreographer to watch.”

Shortly thereafter, renowned dancer Alan Barnes, principal dancer with the Frankfurt Ballet, spent the summer in New York working with the Ailey company. At the end of the summer, he evaluated the dancers.

“In his evaluation – I’ll never forget, I still have it – ‘Ja is a fantastic dancer who shows great potential to be an amazing leader one day, given the opportunity.’ And that stuck with me. Literally, I still have that sheet of paper,” Ja’ Malik says.

Since then, he’s worked with companies across the country, including Cleveland Ballet, Oakland Ballet, North Carolina Dance Theatre, Nathan Trice Rituals, City Dance Ensemble, Ballet Hispanico, and Ballet X. Just over two years ago, Darwin Black, a friend and collaborator who’d been a guest artist with Madison Ballet, told him the company was looking for a new artistic director. Ja’ Malik reached out … and then the pandemic happened, putting the process on pause. But almost two years later, it resumed, and the company was still interested. Ja’ Malik did a little checking up on Madison, though, as he’d never been to Wisconsin – and was warned that there wasn’t a lot of Blackness here.

“I had moved a few times for certain jobs. And I just wanted to make sure that this was going to be the right move. You know, I don’t want to commit to something just because. I want to commit to something because I was passionate about it,” he says. “If I’m happy doing the work, I can live anywhere.”

“A fight for respect”

Jacob Ashley didn’t get quite as early a start. As a high school football player, he needed some work on his lateral movement; the coach suggested he take up either ballet or volleyball.

He’d already learned some dance; he started out just watching the West Indian Folk Dance Company when company director Alfred Baker said no more watching.

“One day he stopped class and was like, you can’t watch anymore. You got to take a class. And in that class, two dancers were from Chicago Academy for the Arts,” Ashley says. So, when he got the advice to try ballet to get better at football, that’s where he went.

He never went back to football.

“My coach and my father were not happy campers,” he says with a laugh.

Just a couple years later, one of his teachers, Guillermo Leyva, was working with the Chicago Festival Ballet and needed “a few extra guys,” Ashley says. “It was sort of like my big break, and the time to really see what it was like to be a professional dancer. And from then on, I was like, alright, I think this is where I want to be.”

Like Ja’ Malik, he often found himself one of just a few dancers who weren’t of purely European heritage.

“It was a fight for respect,” he says. “I just had to work really hard to be seen. Just like with anything, just like in football, if you’re good, people know who you are. You work hard, people will know who you are.”

He first appeared as a guest artist with Madison Ballet in 2007, after impressing former artistic director W. Earle Smith at an audition in Chicago in 2006. He traveled the country as a guest artist with various companies until deciding to join the company here in Madison a few years ago, performing as well as teaching. Late last year, outgoing artistic director Schumann urged him to put his hat in the ring for the open job as school director.

“I’ve been here for so long. The rapport that I have with everyone, just a familiarity with Madison. It was a difficult decision, because it takes me away from the stage. It was a pretty good decision. I think it was worth it,” he says. “The connections that I’ve been able to make have been great. I’ve never received this sort of attention for teaching and being in a teaching role. The biggest thing for me is the kids, the students that I have. A lot of them have been involved with Madison ballet for a very long time. And they’ve seen me grow, and their parents have seen me grow. And the support that they’ve given has been out of this world.”

It felt all the more worth it when a parent wrote him a note after a recent class, letting him know the little girl hadn’t stopped dancing long after they got home from class.

“That makes me feel so good about what I’m doing. And it also lets me know I’m doing the right thing, and I’m really reaching out to the kids,” he says. “And it’s not just me – the lovely team of teachers that I have as well, I try to encourage them to dig deep in their personalities, even though we get tired, even though we had a long day. You got to make it happen for the babies.”

“We have a lot to say.”

Ideally, Ashley will identify and develop talent that can feed into the performance company, which Ja’ Malik says will usually have about 21 members. Both say they hope to diversify the company’s membership to present a more inclusive product.

“I just want to give us a really strong brand identity. So you know that this is a ballet company that is not just a classical company, but can perform a wide variety of ranges within the genre of contemporary, modern, postmodern, neo classical and classical ballet,” Ja’ Malik says.

He also wants Madison Ballet to become known as inclusive and accessible.

“A lot of people think it’s a very elitist art form. It’s only for a certain demographic, a certain sociological background, economic background,” Ja’ Maik says. “I just want to help demystify that, you know, and let people know that (ballet) is for everybody. One of my main goals is in the next two years to really lift the profile of the company, to attract the talent and the talent of color that we need here. I want (dancers) to think there’s this amazing company in little old Madison, Wisconsin. It might be a small city, but the work I want to do here is on that same level of power, passion and precision. I think the plan that I have will attract more dancers of color. It’s just a matter of giving us a little bit of time to execute that.”

“We have people with different pronouns, gay, lesbian. We have so many different people from all walks of life,” Ashley says. “And everyone has been included here.There’s never been any typecasting. We want our audience to broaden its horizons. To know that there are more Black dancers that are working hard to get to the professional level to present themselves at the highest caliber.

“Our presence is rising, but it’s still small. We have a lot to say, too,” he adds.

He says he especially hopes, in a very sports-centered town, young Black boys can find a home in his school, the way he did in Chicago as a teen.

“I want them to know that it’s okay to express themselves, it’s okay to be themselves,” he says. “And then, because we’re in a profession where you have to fulfill a role, if you’re not in tune with being yourself, you get to be someone else for an hour. I just encourage them to just really, really dig deep and be themselves.”

For Ja’ Malik, the commitment to diversity isn’t just among the dancers.

“We want to be a leader in providing a space for new and emerging choreographers, especially choreographers of color, more female choreographers, for sure,” he says. “And we also want to be a place that preserves our heritage, which is classical ballet. We don’t want to eliminate those, but … my vision is to make them more inclusive.”

“It’s for everybody.”

Both men said Madison audiences are ready to take in more ballet, even if they don’t think so.

Ja’ Malik says it’s like watching the Olympics – you don’t have to know anything about gymnastics or figure skating to enjoy it.

“You don’t have to know everything that’s going on. But you watch it for a reason,” he says. “You either like the athleticism of it, or you like the music, the costumes, the theatrics of it, there’s something you find appealing about watching the Olympics. It’s the same when it comes to ballet. But for some reason, when we think about ballet, we think, ‘Oh, that’s beyond my imagination or my means, this is not for me.’ And I’m like, it’s for you. It’s for everybody.”

“Ballet has its European history, but know that we have two people of color here in (leadership roles at) this institution,” Ashley says. “I don’t want anyone to feel as if they’re left out, or they can’t be here. Or feel as if they are singled out because their skin color is different. We don’t promote that. We can’t have that here. But I definitely want people to know: come, come, come. We’re here. The doors are open.”