Through Black History Month, Madison365 has published stories from the History of Black Madison, provided by National Guardian Life Insurance Company.

Through Black History Month, Madison365 has published stories from the History of Black Madison, provided by National Guardian Life Insurance Company.

Part 1: The Founders

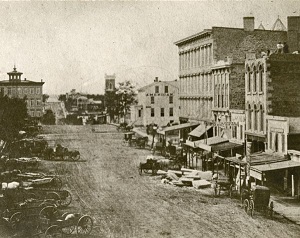

The history of Black Madison is as long as the history of the city itself.

Longer, in fact.

The first known Black resident was a servant to the owner of the American House hotel, on the corner of Pinckney and Washington on the Capitol Square. She arrived in 1839, a year after the hotel was built, and is believed to have stayed for about six years. Her name is lost to history.

The first Black resident whose name survives in the records was Darky Butch, one of six Black residents in 1847, when the population of the town was 632. Butch apparently lived alone with no familial connections nearby.

More Black families began to arrive — along with more people of other races — when Wisconsin became a state in 1848.

The first Black-owned business seems to have been a barbershop opened in 1850 by J. Anderson, who arrived in Madison from Ohio in 1848 and purchased a lot on the corner of Oilman and Henry streets and one at the corner of Hamilton and Dayton streets for a combined $400.

In 1852, 44-year-old Eston Hemings — the son of Thomas Jefferson and his slave, Sally Hemings — moved to Madison, with his wife, who was also multiracial, and their three children. After moving to Wisconsin he adopted the surname Jefferson. Eston passed away just four years later in 1856.

Eston’s eldest son John owned the American House Hotel in the late 1850s, and later served in the Civil War, leading Wisconsin’s 8th Infantry until he was severely wounded, twice, and mustered out of the Army in 1864. He later moved to Memphis, Tennessee.

Eston H. Jefferson’s second child was a daughter, Anna W. Jefferson. She married in Madison but died at just 30 years old in 1866, and little more is known about her.

Eston’s youngest child, Beverly Jefferson, worked for his brother and served briefly in the Civil War before becoming proprietor of the American House. After the American House burned in 1868, he ran the nearby Capitol House hotel. He also operated a carriage and trucking service that brought travelers from Madison’s train stations to the Capitol Square. Beverly Jefferson was well-known among most of the state’s late-19th century political leaders, who stayed at his establishments when the legislature was in session. He lived in Madison until his death in 1908.

The entire Hemings Jefferson family passed as white when they lived in Madison. They are all buried in the Forest Hill Cemetery.

Black people became more and more embedded in the community over the second half of the Nineteenth Century. In 1902, a formerly enslaved person from Kentucky, John Turner, created a center for that Black community when he founded the Free African Methodist Church. In 1911, Madison got its second Black church, Mt. Zion Baptist Church, which originally met at the First Baptist Church downtown before moving to its own building at 548 W. Johnson St. under the leadership of Rev. Zachary Smith in the early 1920s. Rev. Joe Dawson later served as pastor for 30 years, moving the congregation in 1960 to Madison’s South Side, where it continues to thrive to this day.

In 1915, John Hill and his wife Amanda opened Hill’s Grocery on East Dayton Street. In a 2018 interview, their granddaughter Charlyne, who grew up next door to the store, recalled asking her grandparents for penny candy out of the crystal jars that lined the counter and seeing Hill listen to baseball games on the back porch. Amanda was often cooking in the kitchen; Charlyne still uses her custard bread pudding recipe.

In addition to running the grocery store, John was appointed to several city committees, including the Committee on Minority Housing and the Advisory Committee, which encouraged citizen participation in community improvement projects. Amanda served as the Parliamentarian to the Utopia Club, a Black woman’s club that tried to improve social conditions for different marginalized groups in Madison.

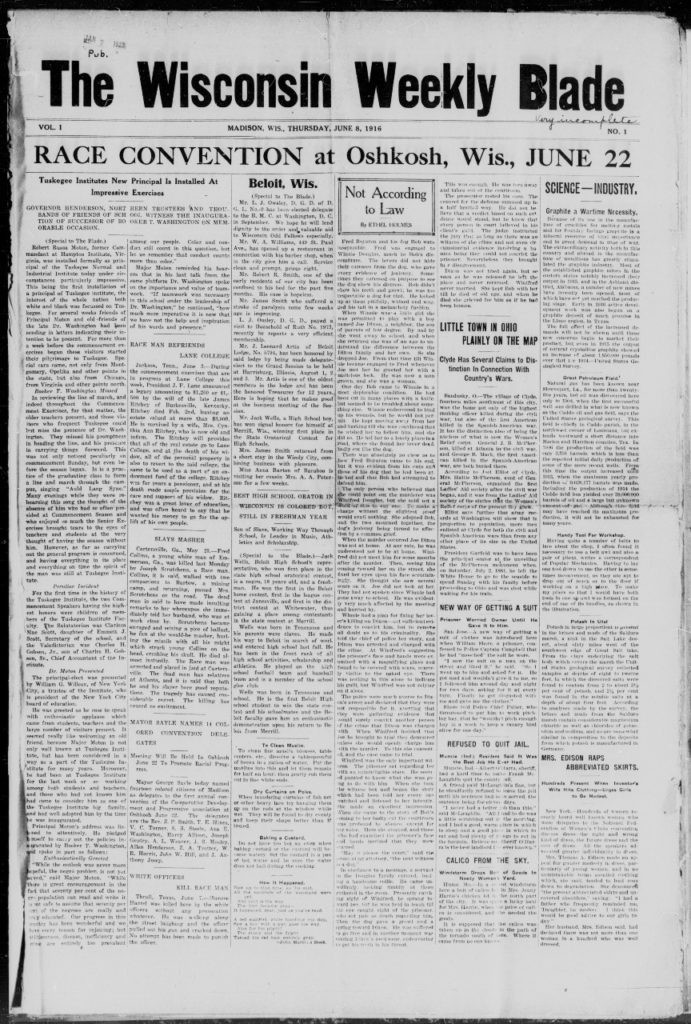

A year after Hill’s Grocery opened, Madison’s first Black newspaper, the Wisconsin Weekly Blade, made its debut. Founded by Madison Black leaders Chestena and J. Anthony Josey, the Weekly Blade was “speaking to and for many thousand colored citizens.” The newspaper ran social notes, church news and other articles of importance to the Black community until 1925, when it moved to Milwaukee and became the Wisconsin Enterprise-Blade, which ran until 1961.

In 1928, Freddie Mae Hill — the daughter of John and Amanda Hill — became the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She majored in Home Economics.

Madison’s earliest Black residents had a lasting impact on the Madison community.

The Hills’ grocery store became one of the longest-running single family-owned businesses in the city, operating until shortly before John Hill passed away in 1983. Today, both the store and the housing attached to it are designated Madison landmarks. The Hills’ eight granddaughters started a non-profit foundation to restore the legacy of their family and their grandparents.

Now located on Fisher Street, Mt. Zion Baptist Church continues to thrive as an anchor of community life on the South Side, operating a food pantry, mental health services and much more.

And descendants of Sally Hemings still live in the area.

Part 2: Madison’s First Black Women

As we noted in Part One, the first Black resident of Madison, Wisconsin, was a woman — a servant at the American House Hotel, who lived here from 1839 until 1845, whose name is lost to history.

Since then, Madison has been home to trailblazing Black women whose names will never be forgotten.

Freddie Mae Hill was the first woman to graduate from the University of Wisconsin. Hill received her Bachelors of Science degree in home economics in 1928.

Today, Hill’s parents’ store, Hill’s Grocery and its attached housing are now designated as a Madison landmark.

Most of Madison’s other first Black women are much more recent.

“Don’t Stop Thinking”

Vel Phillips’ very existence was one of resistance.

In 1951, Phillips became the first black woman to graduate from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School, following which she became the first woman to sit on the Milwaukee Common Council. In 1979, she became the first Black person and woman to be elected to a Wisconsin constitutional office as the Secretary of State. During her time on the Common Council, Phillips introduced the first open housing ordinance in Milwaukee, and fought for it for six years until her death in April of 2018.

She could often be seen attending protests in solidarity against systemic discrimination.

Millie Coby, a long-time Phillips’ family friend noted that beyond her activism, Phillips was an inspiration to those around her.

“We know how she fought for equality, but she did that on a personal note too,” Coby said. “She had a mother’s heart, she never stopped being human. I think that was key to everything. She told me no matter how old you get, you don’t stop dreaming, don’t stop thinking.”

Phillips had such a profound impact on Wisconsin that a movement is underway to have a statue of her placed on the State Capitol grounds.

Changing the police force from within

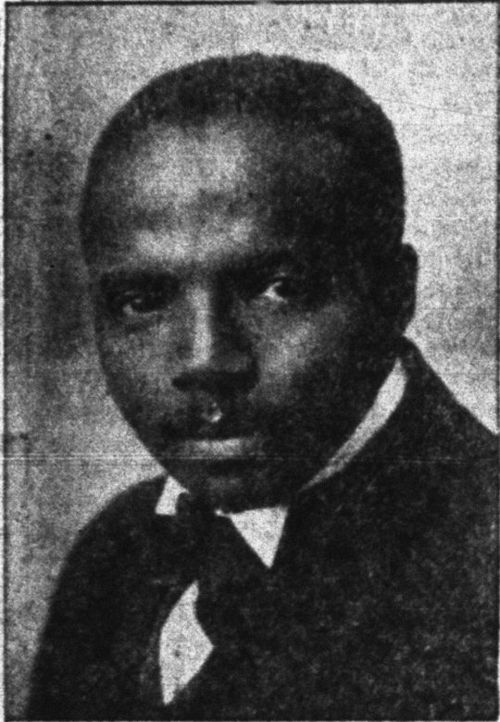

Pia M. Kinney James, the first Black woman to join the Madison Police Department, knew from an early age that she wanted to change the way policing looked in her city.

Pia M. Kinney James, the first Black woman to join the Madison Police Department, knew from an early age that she wanted to change the way policing looked in her city.

“I remember telling my parents I wish I could go to the police department and teach them how to be fair to people,” James said.

And in 1975, that wish came true with her initiation into the force.

In a 2018 interview with Madison365, James noted that she faced discrimination while serving, citing a moment in which a Field Training Officer (FTO) refused to speak to her but said, as she recalls, “I don’t like women in the police department, I don’t like Blacks, and I don’t like people on welfare.”

However, despite the discrmination she faced on the force and the initial aversion from the community, James never faltered on the commitment that she made in her youth to act with integrity and fairness.

“My community slowly learned to accept me and accept the fact that I was gonna be fair to them, and I would say that. I would be upfront: ‘This is what I have to do,’ if I had to make an arrest; ‘This is what I can do,’ if I’m gonna be giving you a break,’” she said.

“My career as a police officer was rough. It was sad and heartbreaking at times, so the joy that I found was helping someone out,” she said. “So, if I helped a family, whether it was a referral or I took an abusive person out the house to make them more safe. For me it was empowerment for that family or that community person that kept me going.”

First Black president not once, but twice

Barbara Nichols was a pioneer not only in health care, but in national healthcare leadership.

As she was coming of age in the late 1950s, “you could have a bachelor’s in physics or a bachelor’s in English, and you would be hired as a maid or a cook,” Nichols said. “The assumption was Blacks did not have the life experience or the intellectual capacity to graduate from nursing school.”

After a stint in the Navy Nurse Corps, she graduated from the Massachusetts Memorial Hospital School of Nursing in Boston and later earned a master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin.

“What I learned early on, prejudice exists when you’re just a staff nurse and you have ideas,” Nichols said in a 2018 interview. “But if you’re a head nurse or a supervisor, or a director, by position, they have to listen to you. So, what I observed out of my experience with prejudice, if I wanted my ideas to be considered, I had to be in a leadership role. Nobody asks you to apply for the leadership roles because they don’t think you’re smart enough. I just did it, and usually was successful. So, what I learned early on, to be accepted for my knowledge, to be accepted for my skill, to be accepted for my abilities, I had to be in a leadership role.”

Soon after that epiphany, Nichols began to get more involved with the Wisconsin Nursing Association and American Nursing Association, moving up the ranks of both organizations. In 1970, she became the first Black president of the Wisconsin Nursing Association and in 1979, the first Black president of the American Nursing Association. She is still active as a community leader in Madison.

It’s about trust

Another first for Madison’s civil servants was Katherine Jackson, who in November of 1990, became the first Black woman in the City of Madison Fire Department.

Jackson had no intention of becoming a firefighter. Only after years of several of her church friends suggesting she enlist did Jackon decide to try out.

In a 2017 interview, James said she joined the force “on a whim.”

Although she faced little discrimination during her time serving as a firefighter, Jackson noted that she was not immune.

“There were a few of the, you know, they call them ‘old timers.’ They weren’t too trusting at first, but eventually I won their trust,” she said.

“[Firefighting] is a job where we depend on each other with our lives when we are going into a burning building,” she said. “They needed to be confident that if we went into a burning building that I could get them out, so I understood their skepticism.”

After 18 years of service, Jackson retired due to knee injuries.

Madame Mayor

Frances Huntley-Cooper made history when she was elected mayor of Fitchburg in April, 1991, becoming the first Black person in Wisconsin to hold that position in any city. She served as mayor until 1993, and remains the only Black mayor in Wisconsin history.

Although she had no previous background in politics, Huntley-Cooper was able to pull from her experience as a social worker.

“I always look at it this way — if you can go deal with children and families, if you can work with a mother and take her child away from them and keep them away while the mother is getting treatment and help, that skill was transferable for when I decided to run for office,” Huntley-Cooper said in an interview.

“You have to go out and knock on doors, talk to people and try to sell them on different issues,” she added.

Today, Frances Huntley-Cooper is a charter member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority – Kappa Psi Omega Chapter, the former president of the Madison NAACP and serving her fifth appointment as a member of the board of trustees of Madison College (MATC).

Madison’s poet

Fabu Carter, artistically known as Poet Fabu, was the first Black person chosen as Madison’s poet laureate in 2008.

Originally from Memphis, Tennessee, Carter has been writing poetry since she was 11 years old.

In an interview with Madison365, Carter said that upon being chosen as Madison’s poet laureate, she gained an invigorated sense of responsibility to both her own Black community and the larger Madison community.

“I not only represented African American people, which was very critical to me, but I was also representing Madison, and in another way I was representing Wisconsin. It just really was a very wonderful experience,” Carter said.

DJ, CEO

In 2017, Vanessa McDowell became the first Black woman to lead the Madison YWCA, a 109-year-old organization dedicated to working against racism, when she was elevated from her previous position as director of support services.

“First of all, it’s humbling to be in this position at this time,” she said at the time. “But to be the first African American CEO in 2017, is also a little disheartening, to be honest. So it’s mixed bag, in terms of my feelings. But I definitely don’t take it lightly and I stand on the shoulders of people in our community who have come before me and am excited to get to work.”

A native of Madison’s West Side, Vanessa’s earned a national reputation, and recently YWCA was given a piece of philanthropist Mackenzie Scott’s $4 billion giving spree.

And to top all that off, she still performs regularly, spinning tracks as DJ Ace.

Part 3: The Educators

“They never saw anybody that looked like them, and never came in contact with any such thing as a teacher of color.”

Geraldine Bernard made that comment to author David Giffey in a story collection called “The people’s stories of South Madison,” published in 2001. Bernard was the first Black teacher at Madison Metropolitan School District. MMSD hired Bernard in the early 1960s and she worked for Silver Spring and then Aldo Leopold Elementary.

After retiring from Leopold in 1989, she continued to volunteer and was a prominent member of Mt. Zion Baptist Church. Today, she is 90 years old and is still remembered as a pioneer and trailblazing educator.

Before MMSD hired Bernard, Helen McLean got an interview to be a teacher in 1958. She would have been the district’s first Black teacher, but the interviewing committee didn’t hire her. The committee chairman said he didn’t think the parents of white students would be comfortable with a Black teacher. The Beloit school district hired McLean but after her story reached the media, Madison hired her and she relocated to Madison to work at Longfellow Elementary.

In 1973, around a decade after students of color started seeing glimpses of representation in Madison, the Madison School Board adopted an affirmative action policy that commits the school district to actively recruit women and people of color.

That same year two south Madison neighborhood centers filed a complaint with the federal Office of Civil Rights claiming racial discrimination by the Madison School District. The courts ruled in June 1983 that the Madison schools were discriminating against minority students in the way it managed school closures and boundary changes.

Dr. John Odom became the first Affirmative Action Officer for MMSD in 1976 and would later become the first Black middle school principal in Madison at Cherokee Middle School.

When Odom died Oct. 30, 2020, Rev. David Hart, an attorney, author, Madison community leader, and pastor of Sherman Avenue United Methodist Church told Madison365 that Odom had mentored countless Black teachers, principals and leaders.

“There is not a single organization in Madison that is focused on Black people that hasn’t either been touched positively by Dr. Odom or influenced by his work, his goodness, his benevolence and his activism,” Hart said.

In 1979, Milt McPike became principal at East High School after holding the vice principal position at Madison West.

During McPike’s time at East, he was named Wisconsin’s Principal of the Year and a Reader’s Digest Hero of American Education. In 2002, President George W. Bush named him one of the nation’s top 10 educators.

Edith Hillard told Madison365 in 2017, nine years after McPike died of cancer, that she still remembers him as a principal making house visits to parents.

“He changed the way things were done at East and we won national awards. I think that was because Milt didn’t just take it as a day-to-day job… it was so much more,” Hilliard adds. “East was part of his life.”

In 2018, the City of Madison named a park in his honor, and in 2020, Madison East celebrated the grand opening of Milton L. McPike Field House.

In 1995, Gloria Ladson-Billings became the first Black woman to earn tenure in UW–Madison’s School of Education. She became one of the nation’s leading scholars of education, pioneering research and scholarship on education debt and critical race theory. She earned more awards and accolades than can be listed here, and retired in 2018. She remains a Madison community leader and regular contributor to Madison365.

In 2013, Dr. Jack E. Daniels III became the first African American to lead Madison Area Technical College in the school’s 106-year history. He led a monumental effort to vacate the college’s downtown location and build a sparkling new campus on Madison’s south side, which opened in 2019.

In January of 2018 after being the first female, African American appointed to serve as an assistant state superintendent, Carolyn Stanford Taylor became Wisconsin’s first Black state superintendent of public instruction. And although she is not running for reelection once her term expires in July 2021, she said she is still committed to education equity.

“Every child in this state deserves the chance, the opportunity, and the supports to become a success,” Stanford Taylor said in Jan. 13 a statement. “This will only happen if we — educators, the governor, legislators, parents, and community members — work together to make sure every student has what they need to learn when they need it.”

On Aug. 4, 2021 Carlton Jenkins became the first Black superintendent of MMSD. He is a University of Wisconsin-Madison graduate and former MMSD employee.

“With this role comes a tremendous responsibility, and although there are challenges we face as a school district, through community engagement and support for schools and teachers, we will work hard to ensure that all of our students are at the center of everything we do, and that the district remains grounded in its strategic framework goals,” he said.

Part 4: The Musicians

Give the drummer some

Clyde Stubblefield was already famous when he arrived in Madison in 1971. The “Funky Drummer” had toured the world with James Brown and had laid down a drum beat that would become the most sampled of all time — and for which he’d never be properly compensated.

Having visited Madison on tour, and having a brother who lived here, he decided to settle here and never really sought the national limelight. He became a staple of the local music scene, though, and the national limelight sought him. His innovative style was recognized in 1990 when he was named Drummer of the Year by Rolling Stone. In 2014, LA Times named him the second-best drummer of all time, and in 2016, Rolling Stone again honored him, putting him in the top 10 of all time.

From the early 1990s to 2015, he performed on the nationally syndicated public radio show “Michael Feldman’s Whad’Ya Know” on Wisconsin Public Radio. He also performed every Monday night downtown Madison with The Clyde Stubblefield Band for many years.

In 2000, he was inducted into the Wisconsin Area Music Industry Hall of Fame. In 2004, he received the lifetime achievement award at the Madison Area Music Awards. Madison Mayor Paul Soglin declared Oct. 10, 2015, Clyde Stubblefield Day. His drumsticks are part of an exhibit in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

On the 1970 James Brown song “The Funky Drummer,” Stubblefield improvised a drum break that’s estimated to have been sampled more than 1,500 times by acts like Public Enemy, N.W.A, LL Cool J, Run-DMC and the Beastie Boys, and later pop musicians such as Ed Sheeran and George Michael. Because he was not given songwriter credit on the track, however, Stubblefield did not receive any royalties for those samples.

His first solo album, Revenge of the Funky Drummer, came out in 1997, followed by two more solo albums and many collaborative projects.

After Stubblefield died in 2017, The University of Wisconsin honored him with a posthumous honorary doctorate.

“It is impossible to overstate the impact Stubblefield has had on the world of drumming,” said UW-Madison Professor of Percussion Anthony Di Sanza in a letter nominating Stubblefield for the degree. “He has inspired generations of drummers with his syncopated, yet flowing rhythmic grooves that combine effortlessly with his unique musical taste and sensibility. For many of us living in the world of drums and percussion, he is a trailblazer and a hero.”

The Venues

The same year that Stubblefield arrived in Madison, Roger Parks opened a bar on the south side — Mr. P’s — which became virtually the only place to hear live jazz in Madison for years. It also became the “war room” for Roger’s son Eugene, who would later become the City of Madison’s affirmative action officer and launch a years-long campaign against the city — including federal lawsuits and two campaigns for mayor — after being fired in 1988.

Mr. P’s lasted until 1998 and overlapped with another effort to create a venue for jazz closer to downtown. Sax player Hanah Jon Taylor, recently relocated from Chicago, opened House of Soundz on Williamson Street in 1994, but it only lasted two years. Undeterred, Taylor opened Madison Center for Creative and Cultural Arts in 2003, which operated until 2007. A decade later he opened Cafe Coda inside The Fountain on Dayton Street as a space where both longtime practitioners of jazz, students of jazz, and appreciators of the genre can gather to learn and listen in community. A year later he moved back to Willie Street, opening the new Cafe Coda in September of 2018. It’s still going strong, thanks in part to community support to survive the pandemic.

Mr. P’s lasted until 1998 and overlapped with another effort to create a venue for jazz closer to downtown. Sax player Hanah Jon Taylor, recently relocated from Chicago, opened House of Soundz on Williamson Street in 1994, but it only lasted two years. Undeterred, Taylor opened Madison Center for Creative and Cultural Arts in 2003, which operated until 2007. A decade later he opened Cafe Coda inside The Fountain on Dayton Street as a space where both longtime practitioners of jazz, students of jazz, and appreciators of the genre can gather to learn and listen in community. A year later he moved back to Willie Street, opening the new Cafe Coda in September of 2018. It’s still going strong, thanks in part to community support to survive the pandemic.

All about that bass

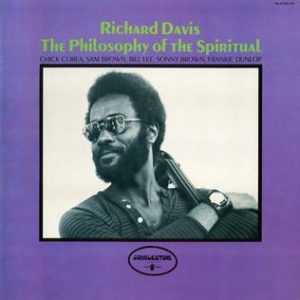

Another giant of Madison’s jazz scene was also a transplant, who arrived in 1977. Like Stubblefield, bassist Richard Davis was already world-renowned when he came to Madison. Starting in the 1950s, he became one of the best-known and most in-demand studio and performance bassists in the world. He recorded with folk, jazz, and rock artists from Miles Davis to Van Morrison to Bruce Springsteen, and he also performed under Igor Stravinsky, Leonard Bernstein, and many others.

Another giant of Madison’s jazz scene was also a transplant, who arrived in 1977. Like Stubblefield, bassist Richard Davis was already world-renowned when he came to Madison. Starting in the 1950s, he became one of the best-known and most in-demand studio and performance bassists in the world. He recorded with folk, jazz, and rock artists from Miles Davis to Van Morrison to Bruce Springsteen, and he also performed under Igor Stravinsky, Leonard Bernstein, and many others.

A Chicago native, he decided it was time to return to the Midwest and begin to pass on his knowledge and experience to the next generation. He finally relented to the incessant recruiting of the University of Wisconsin, joining the music faculty in 1977.

“I should be careful what I say” about his first impressions of Madison, he said with a gravelly chuckle in a recent interview. “It was kind of laid back and slow. Different rhythm. I had to regroup and lessen my expectancy. [The students] didn’t know anything. They didn’t know about jazz. They never answered any questions I asked them. They didn’t know anything.”

Peter Dominguez, one of Davis’s first students, helped him launch the Richard Davis Foundation for Young Bassists, an independent nonprofit organization that hosts an annual conference where young bass players, ages 3 to 18, can learn from and perform with masters from around the country. Around the same time that nonprofit was getting started, Davis started another effort to solve another, bigger problem — racism in liberal Madison.

“People say Madison is very liberal. It’s not,” Davis says. “I saw a need for change.”

He heard a radio show about racial healing classes and thought it was a good idea. He got some training himself and ran a weekly class for more than 25 years.

He says things have changed a bit, noting especially that the UW’s Mead Witter School of Music has more faculty of color. But that’s not enough.

“Still racism going on,” he said. “I keep in touch with people [on campus], and they tell me what’s happening and what’s not happening.”

But he also knows quick change was never a realistic goal.

“When I first came here 40 years ago, in ’77, I met people who had come here 20 years before I got here, and they said nothing had changed since they were there,” he said. “Racism is not an easy thing to wipe out. It perpetuates itself all the time. School systems remain the same, administration remains the same. You don’t see changes that are rapid.”

So you just have to be patient?

“You can be patient all you want to,” he says with a chuckle. “That isn’t gonna do anything either. But you have no other choice.”

Now 90, Davis has a street named in his honor on Madison’s east side.

Gettin’ fresh

Right around 1984, a group of Madison West students started performing original rap and hip-hop tunes at local talent shows. Erin “DJ Sweet E” Hynum, Johnny “Savior Faire/J-Law” Winston Jr., Emanuel “MC Yokes” Whitfield, Oren “Finesse” Ben-Ami, and Richard “Daddy Rich” Henderson would become Fresh Force, the first Madison-based hip-hop act to be signed to a national record deal.

“The hip hop scene, the urban music scene in Madison was pretty sparse at that time,” Winston said in a recent interview. He recalled the group’s first 45 EP as “a big deal.” Recorded in 1987 by Butch Vig at Smart Studios (the same studio that would later produce Nirvana’s seminal album Nevermind), the record included the tracks “We Rock the House”, “Always Together”, and “Prejudice.”

Fresh Force performed regularly around Madison, Milwaukee and Chicago and appeared in commercials for American TV, as well as the 1990 census and other local agencies.

“I mean, we rapped about everything,” Winston said with a laugh.

“We were pretty local and we had a good time doing what we’re doing and I wish we had the technology that the young people have today,” he said, such as SoundCloud, Spotify and YouTube.

Fresh Force got national airplay and distribution after they signed with Chicago-based record label DJ International. They also shared the stage with some huge names, performing with and opening for such artists as Speech (from the Grammy-winning group, Arrested Development), Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam, Ready for the World, EPMD, Glenn Medeiros, The Cheaters, and Fast Eddie.

“It was just five guys having a whole lot of fun together and making some cool music and stuff we can still talk about today,” Winston said.

“Everybody grew up” by 1992 or so, and the group’s performance career faded as the members embarked on other careers. Winston became a Madison firefighter and school board member. Hynum became owner of The Underground (a music venue where Fresh Force, ironically, never performed) and now works as a chief financial officer. Henderson owns a custom t-shirt company.

Winston fondly remembers those days, and said it’s important to remain connected to your hometown.

He said he’d advise any young artists to “perform as much as they can. Record as much as they can and use the mediums that they have at their disposal. The SoundClouds, the YouTubes, again all this stuff we didn’t have, the internet and everything else,” he said. “But what really makes an artist is people in their own hometown relating to them. If you have a buzz in your own hometown, that’s a great thing. So people who live in Madison, they shouldn’t forget Madison, they shouldn’t forget to make a name for themselves here and have a whole lot of fun doing it.”

Ayomi Wolff, Mackenzie Krumme and Robert Chappell contributed to this report.