Through Black History Month, Madison365 will publish stories from the History of Black Madison, provided by National Guardian Life Insurance Company. Today: The Founders.

Through Black History Month, Madison365 will publish stories from the History of Black Madison, provided by National Guardian Life Insurance Company. Today: The Founders.

The history of Black Madison is as long as the history of the city itself.

Longer, in fact.

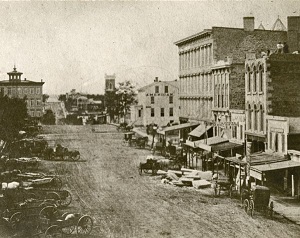

The first known Black resident was a servant to the owner of the American House hotel, on the corner of Pinckney and Washington on the Capitol Square. She arrived in 1839, a year after the hotel was built, and is believed to have stayed for about six years. Her name is lost to history.

The first Black resident whose name survives in the records was Darky Butch, one of six Black residents in 1847, when the population of the town was 632. Butch apparently lived alone with no familial connections nearby.

More Black families began to arrive — along with more people of other races — when Wisconsin became a state in 1848.

The first Black-owned business seems to have been a barbershop opened in 1850 by J. Anderson, who arrived in Madison from Ohio in 1848 and purchased a lot on the corner of Oilman and Henry streets and one at the corner of Hamilton and Dayton streets for a combined $400.

In 1852, 44-year-old Eston Hemings — the son of Thomas Jefferson and his slave, Sally Hemings — moved to Madison, with his wife, who was also multiracial, and their three children. After moving to Wisconsin he adopted the surname Jefferson. Eston passed away just four years later in 1856.

Eston’s eldest son John owned the American House Hotel in the late 1850s, and later served in the Civil War, leading Wisconsin’s 8th Infantry until he was severely wounded, twice, and mustered out of the Army in 1864. He later moved to Memphis, Tennessee.

Eston H. Jefferson’s second child was a daughter, Anna W. Jefferson. She married in Madison but died at just 30 years old in 1866, and little more is known about her.

Eston’s youngest child, Beverly Jefferson, worked for his brother and served briefly in the Civil War before becoming proprietor of the American House. After the American House burned in 1868, he ran the nearby Capitol House hotel. He also operated a carriage and trucking service that brought travelers from Madison’s train stations to the Capitol Square. Beverly Jefferson was well-known among most of the state’s late-19th century political leaders, who stayed at his establishments when the legislature was in session. He lived in Madison until his death in 1908.

The entire Hemings Jefferson family passed as white when they lived in Madison. They are all buried in the Forest Hill Cemetery.

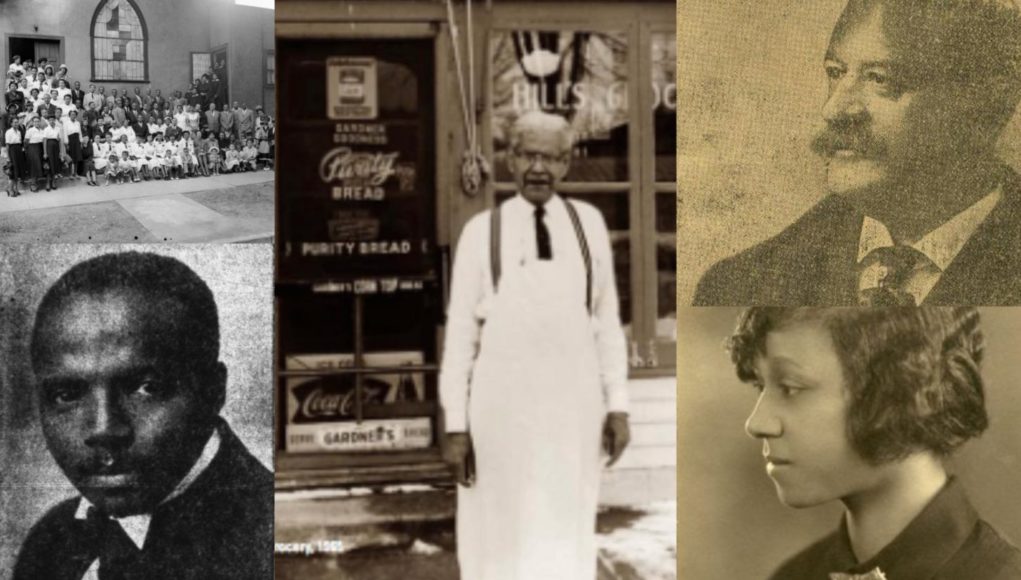

Black people became more and more embedded in the community over the second half of the Nineteenth Century. In 1902, a formerly enslaved person from Kentucky, John Turner, created a center for that Black community when he founded the Free African Methodist Church. In 1911, Madison got its second Black church, Mt. Zion Baptist Church, which originally met at the First Baptist Church downtown before moving to its own building at 548 W. Johnson St. under the leadership of Rev. Zachary Smith in the early 1920s. Rev. Joe Dawson later served as pastor for 30 years, moving the congregation in 1960 to Madison’s South Side, where it continues to thrive to this day.

In 1915, John Hill and his wife Amanda opened Hill’s Grocery on East Dayton Street. In a 2018 interview, their granddaughter Charlyne, who grew up next door to the store, recalled asking her grandparents for penny candy out of the crystal jars that lined the counter and seeing Hill listen to baseball games on the back porch. Amanda was often cooking in the kitchen; Charlyne still uses her custard bread pudding recipe.

In addition to running the grocery store, John was appointed to several city committees, including the Committee on Minority Housing and the Advisory Committee, which encouraged citizen participation in community improvement projects. Amanda served as the Parliamentarian to the Utopia Club, a Black woman’s club that tried to improve social conditions for different marginalized groups in Madison.

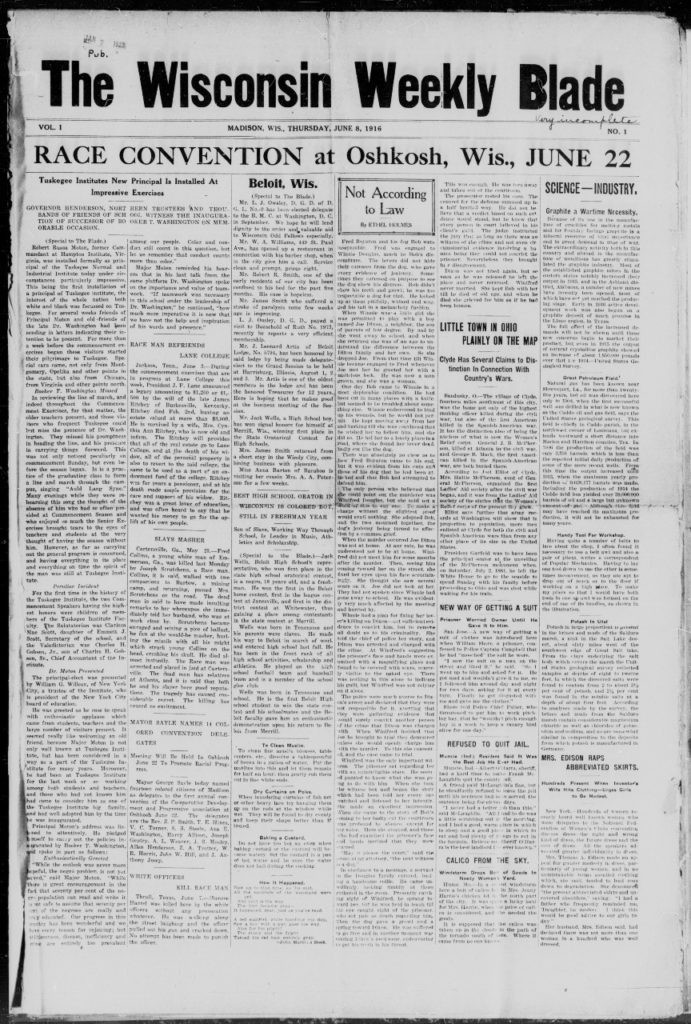

A year after Hill’s Grocery opened, Madison’s first Black newspaper, the Wisconsin Weekly Blade, made its debut. Founded by Madison Black leaders Chestena and J. Anthony Josey, the Weekly Blade was “speaking to and for many thousand colored citizens.” The newspaper ran social notes, church news and other articles of importance to the Black community until 1925, when it moved to Milwaukee and became the Wisconsin Enterprise-Blade, which ran until 1961.

In 1928, Freddie Mae Hill — the daughter of John and Amanda Hill — became the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She majored in Home Economics.

Madison’s earliest Black residents had a lasting impact on the Madison community.

The Hills’ grocery store became one of the longest-running single family-owned businesses in the city, operating until shortly before John Hill passed away in 1983. Today, both the store and the housing attached to it are designated Madison landmarks. The Hills’ eight granddaughters started a non-profit foundation to restore the legacy of their family and their grandparents.

Now located on Fisher Street, Mt. Zion Baptist Church continues to thrive as an anchor of community life on the South Side, operating a food pantry, mental health services and much more.

And descendants of Sally Hemings still live in the area.

Throughout this month, thanks to the support of National Guardian Life Insurance Company, we will bring more stories from the lasting legacy of Madison’s Black community over the decades.

Coming next week: Madison’s First Black Women.