Milwaukee is and has always been America’s beer capital, so perhaps it makes perfect sense that the country’s first African American brewery was born here.

Theodore Mack Sr. was a former Pabst employee with a dream to launch America’s first Black brewery. A man of action, Mack assembled a group of investors under the United Black Enterprises banner with the hopes of purchasing the Blatz brand from Pabst in 1969 after the federal government forced its sale.

Mack told reporters that UBE made is $8 million offer on “behalf of the 22 million black people in this country.”

Although that fell through, 40-year-old Mack – a former social worker who’d spend five years as a production supervisor at Pabst – was not dissuaded.

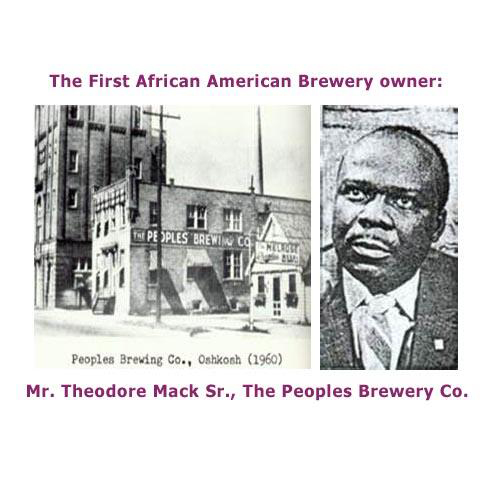

“We decided we would keep looking for a brewery,” Mack later said. What they found was Peoples Brewery, founded in Oshkosh in 1912 by Bavarian-born Joseph J. Nigl. Peoples ranked 10th among the 14 breweries in Wisconsin at the time. (Peoples should not be confused with the current brewer, People’s, located in Lafayette, Ind.)

“We decided on Peoples Brewery here in Oshkosh because the location was close to Milwaukee and the physical plant was in good shape.”

By April 1970, Mack and company made a deal to buy Peoples for a reported $365,000 plus another $70,000 for inventory, and Henry S. Crosby, spokesman for the group, explained its importance to the Milwaukee Courier:

“There are no other Black breweries anywhere in the U.S. and hardly any Black businesses of this size. … (It’s important because) one, (it will) place Blacks in decision-making position, and two, offer stock to the members of the Black community as soon as the mechanism is set up.”

And that stock was the key for Mack. He told reporters at the time that he hoped the community would get involved in the business and buy shares to make the venture a successful one for the African American community.

By mid-summer, it was reported that 65,000 shares at $5 a piece had been issued. Not long after, Peoples bought a complex at 3002 W. Wright St. in Milwaukee with a garage, office space, and a small warehouse. In November, as production began in late autumn with a special holiday beer, Mack told the Milwaukee Journal that Peoples had about 1,000 stockholders.

At the same time, Peoples was focusing on integration, and all 21 of the employees at the brewery – which was pumping out about 25,000 barrels of beer each year – were kept on. Although it wasn’t running at capacity, the brewery was already producing more beer than previous owners had. At the end of the year, the company had added 15 more employees.

“Our next task is to integrate our employment in Oshkosh and Milwaukee,” Mack told a local newspaper in November 1970. “We have no White employees here and no Black employees in Oshkosh. We’re going to have to change that.”

Always looking ahead, Peoples tried to get lucrative contracts to supply beer to the military, and in June 1971 Mack announced plans to expand operations into Indiana. Although 24,000 shares of stock remained unsold, the beer was already being distributed to Milwaukee, Madison, Racine, Kenosha, Sheboygan and northern Chicago. Now, they focused on distributing to retailers in Gary.

In November 1971, Peoples bought the 107-year-old Oshkosh Brewing Co. and its Chief Oshkosh, Badger and Rahr brands. Mack told a reporter Peoples bought Oshkosh because “he felt big breweries were trying to squeeze out the little man and he did not want to bow to the pressure.”

But things were not going down all that smoothly, and as Gov. Pat Lucey declared that Peoples was, “One of the really shining examples of minority capitalism” in the U.S., the brewery – which was turning out 1,800 barrels of beer per month – was struggling.

In September, a Greater Milwaukee Star headline declared that Peoples might leave Milwaukee.

First of all, there was trouble in Indiana. Peoples wanted to distribute to retailers and that was against the law, according to officials there. A Teamsters strike in the Hoosier state didn’t help, either. But Mack was skeptical, citing harassment and opposition from other brewers and distributors.

“Everywhere we go,” he was quoted in one newspaper, “we run into the White power structure.”

But it wasn’t just the White population that Mack thought was dooming Peoples.

Mack told the Star, “The Whites are saying that they don’t want no n—– beer and I don’t know what the Blacks are doing.” He balked at accusations that Peoples beer wasn’t up to snuff.

As difficult as Indiana was, Mack cited figures that it took only a week in Gary to sell as much Peoples beer as he sold in Milwaukee in a month, and his disappointment was clear.

“Here you have over 100,000 Black people saying we want to do our thing and when you give them this opportunity, they don’t respond.”

A year later, Peoples talked about leaving Milwaukee once again, this time for Mack’s native Alabama. But it was all moot as workers were laid off and the brewery idled due to an IRS lien for unpaid taxes. Peoples also defaulted on a $390,000 bank loan.

Mack called a stockholders meeting for Feb. 20, 1973, at Jabber’s Bar, a tavern next to the Oshkosh brewery. The announcement discussed a lawsuit against the government, the threat of bankruptcy and a trip to Nigeria, although Mack said he was “not in a position to reveal what transpired,” in the West African nation. But it was too late, People was finished.

In a time of brewery consolidation and during the reign of the brewing giants, it’s amazing Peoples lasted as long as it did. Trouble had come to a head for Peoples but Mack, Crosby, and their cohorts had established America’s first Black brewery and set a positive example with their ambition, drive and success.