As a child, Johanna Heineman-Pieper asked her parents to write down all the stories they told her.

A thousand miles away, another little girl asked the same of her father.

They didn’t know each other. Neither knew the other existed. And neither knew they were sisters — until just a few months ago.

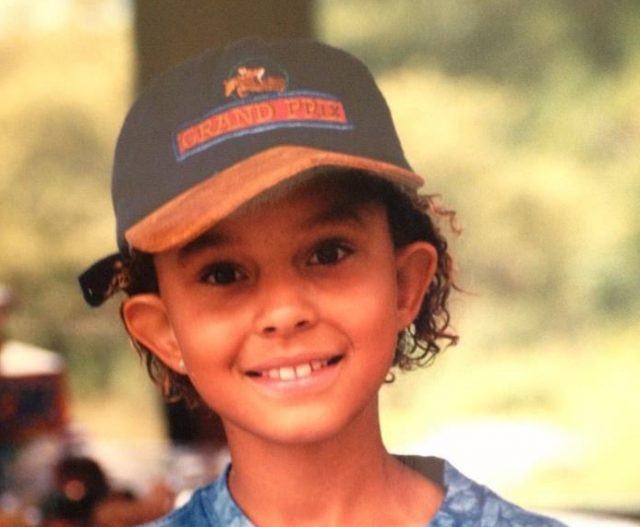

She always knew she was adopted. Her parents didn’t want to keep it a secret — not that they’d be able to anyway, considering the clear difference in melanin levels.

“I’ve always been a very proud adoptee,” says Heineman-Pieper, now 27 and living with partner Shawna Lutzow in Madison.

One thing that was kept secret, however, was the identity of her birth parents. When she was born and adopted in 1991, most adoptions were still “closed,” meaning adopted children and parents had little or no information about or contact with birth parents.

“I always kind of knew, ‘a few fun facts,’ is what I called them, about my birth parents,” Heineman-Pieper says. “They were both students at a college in Illinois. My mom was about 5’3″ and played the flute, and she was white. And my birth father was Native American, about 6’3″ and ran track. And that’s kind of all I knew.”

Growing up, Heineman-Pieper felt a connection to that Native American heritage, even though she had no idea what indigenous nation she might belong to.

“But then when I would look in the mirror, when other people looked at me, there were a few instances where they were like, ‘Nope, you’re not Native girl, you’re Black!’” she says. “And I was pretty defensive about that, because I kind of grew up and it was like, being Native American is cool and I’ve always had a connection to animals and all that kind of typical Native American things that you think are cool.”

Growing up as a brown kid with kinky hair in an all-white family instilled a sense of wondering.

“We never really talked about race in my family because they had this color blind approach, where it was like, ‘You’re just who you are and we love you. There’s no need to talk about race because we think you’re special and great,’” she says. “I really learned that we should’ve gone into race things, and I formed a really nice community of folks who kind of helped me start getting really comfortable with this whole process … Not knowing specifically my history and my roots also just kind of started to get at me.”

It wasn’t that she felt anything lacking in the family that raised her.

“I think a big reason why I didn’t really pursue finding my birth parents until the last few years, is because I didn’t want my mom or dad to feel like they hadn’t done a good job and they weren’t as important,” she says.

But two years ago, she and Lutzow attended a conference in Philadelphia that included a transracial adoption workshop .

“That was awesome. I never realized that being a transracial adoptee was a thing,” she says.

Claiming that identity sparked an interest to finally go ahead and look into those birth parents beyond the “fun facts.” She started with her birth certificate, which listed only her birth mother’s name. A bit of online searching yielded an email address, which she wrote to in April 2017.

“I wrote a little essay type of deal, just because I knew that maybe she did think about me every now and then but I was kinda just like, popping out of nowhere,” she says. But the email she got back wasn’t encouraging — in fact, the woman wrote back that she had no idea what Heineman-Pieper was talking about.

Undeterred, Heineman-Pieper wrote again, sharing some of those “fun facts” that she knew. This time the woman’s husband responded, asking her not to email again, but inviting her to call if she wanted, which she did — only to learn that the woman she’d found was, in fact, her birth mother — but didn’t want any contact because “it was a traumatic experience for her.”

Disappointed but undaunted, Heineman-Pieper turned to her birth father, whom she knew next to nothing about.

“I kind of hit a dead end with my racial discovery journey, because the birth father’s name wasn’t listed, (my birth mother) didn’t want to talk about it at all, and I’m like, okay, what do I do now?” she says. So she started looking at photos, seeking out a resemblance to her own most distinctive physical feature.

“I looked back through the yearbook of where they went (to college), and I looked at ’89, ’90, and ’91 and looked at pictures of the track team,” she says. “I remember kind of scrolling through and taking screenshots of the yearbook, and looking at him, and I was like, okay, so which one has my ears?”

She reached out to one man who she felt might resemble her enough, but that was a swing and a miss. Ultimately she decided to go the scientific route, and get DNA tests from both 23 and Me and AncestryDNA in the fall of 2018.

“I get some results back, and then the next day it said that I have a highly, extremely likely parent-child match with this guy named Anton,” she says — a guy named Anton who had, coincidentally, just done his own AncestryDNA test just a few months earlier.

Back to the yearbooks she went, to find a member of that track team named Anton Morris.

She then reached out to him through Ancestry.com’s messaging function, and found out he never even knew she existed.

“He was like, ‘Wow, this is shocking. If this is true, then maybe you have some of these qualities.’ And some of the qualities that he listed in this message were just … eerily accurate,” she says.

“I don’t really know if I had a particular reaction” to learning he had another daughter, Morris says. “The only question was what were the details? That’s really what I was curious to know.”

One of the first things she learned was that she should have embraced what all those people said about her clearly being Black — considering her biological great-grandmother was a Black Panther.

“I already kind of accepted that I was part black, just mostly because of my hair. But it was really helpful just to kind of see” for sure, she says.

“I usually identify with being West African more than anything else,” Morris says, but a Choctaw line of his family is still important to his heritage. There isn’t a lot of Native American information in the AncestryDNA database, though, so that line doesn’t show up in his genetic profile.

“Fortunately, my side of the family always kept up with our heritage and stories,” he says — stories he now wants to share with Heineman-Pieper. “My grandmother and some uncles are really big on telling the stories. I was about fifteen years old when I decided I should start writing them down. So I started doing that and writing down all the stories that I was told coming from West Africa and here is some plantation life and things like that. I was fortunate enough to get a wealth of knowledge from a lot of the older people who are no longer with us.”

Now living in the Las Vegas area, Morris and his 20-year-old daughter are excited to get to know Heineman-Pieper, and make up for lost time.

“I don’t know if upset is the word, just cheated more than anything else,” Morris says of how he feels today. “That’s really it. When you look at the pictures and things she had, like with the basketball games and things like that … (it) kind of sucks to miss out on those things.”

Morris also shared a bit about Heineman-Pieper’s beginnings with her.

“He said, ‘I am not proud to say that I had relations with different women and did not commit to any relationship,’” she says. “That had me laughing, because there was also a time in my life in college where I was like, the ultimate player.”

Morris also shared some stories of his family, which includes several generations of racial justice activists — which has also been an important part of Heineman-Pieper’s life.

“It was just a cool piece of family history, which I think is interesting because I have such a passion for justice and always have,” she says. In fact, she and Lutzow have been leading a new discussion group on “Conversations About Racism in Queer Communities” and she was one of the driving forces behind having law enforcement agencies removed from last year’s Pride Parade.

After several email and phone conversations, Morris invited Heineman-Pieper to visit Las Vegas, which she hopes to do next month — with a little help from the community.

“The next step was, we gotta go to Vegas and we gotta meet him. We have to compare the ears side by side,” she says. “So we’ve been kind of looking for deals. We’ve heard people can get cheap tickets to Vegas and we just weren’t finding any. We’re like, okay, we just gotta do it because the longer we delay … life just kind of happens, and I don’t want it to be right here before my eyes and not really live it.”

So to do it, she’s turned to the community for help, setting up a GoFundMe fundraiser seeking $1,500 for travel expenses. As of Wednesday, she’s raised $750.

“The people have really been amazing and supportive,” she says, as has her family. “They’ve all just been really, really supportive and are just excited for me. I never wanted my family to feel like they weren’t good enough, (or that) I needed to find another family. That wasn’t my motivation. It’s really great because they’re communicating to me that they don’t feel like they’re in second place, they’re more just excited for my journey and are supporting me.”

Her motivation, she stresses, is only about her own identity — personally as well as racially.

“You know, even if you feel a hundred percent loved, there’s always a little bit of … trying to get accepted,” she says. “I realize that in my own life, I always thought that I had to do so much better than my sisters in order for my family to truly accept me and love me as one of their own.

“I grew up thinking that I was just literally like, half white and half Native American, not even really open to being multiracial or whatever. Anton’s really just accepted everything about himself racially. He is literally mixed and is interested in kind of confirming certain things that are also on the Native American side.”

“I was just really interested in getting her all the information that she would personally want” about her biological family and their background, Morris says. “So that she can feel as whole as possible. That’s why I wasn’t angry. I didn’t have time to be angry, cause those were the types of thoughts that were in my mind.”

Even though he wasn’t angry about not being told he had a daughter, he wants her to know he wishes things could have been different.

“It would have been real cool if I had known,” he says. “If I had known she would have never been adopted.

“I kind of wish her Dad was alive still,” he adds of Heineman-Pieper’s adoptive father, who passed away in 2014. “I would have loved to be able to shake his hand, basically tell him thanks. Good thing is she was able to grow up with some kind of love and affection, and had a family and a normal life. That’s good. I appreciate that.”

If her fundraiser meets its goal, Heineman-Pieper says she is excited to meet Morris and her half-sister, but doesn’t have any particular expectations.

“I (found my birth father) because I was ready,” she says. “And I just kind of did it on my own terms. It took a little while. And it just, it was out of … therapy, and processing and just talking about things, and that’s definitely going to continue leading up to going to meet him and afterwards, just trying to process all this stuff and not having any kind of expectations, and just being who I am.”

And “who I am” is a confident transracial adoptee, a mixed-race Native and Black woman with a penchant for family stories, just like her newfound birth father and sister — even when those stories aren’t simple.

“It’s such a challenging thing really to kind of process,” she says. “Imean, this is literally life. This isn’t some Disney movie that’s gonna end with rainbows and flowers at the end. You have no idea, and it’s so complex. But it’s beautiful. It’s beautiful the entire way through.”

Community members can support Heineman-Pieper’s trip to meet her birth father at GoFundMe.com.