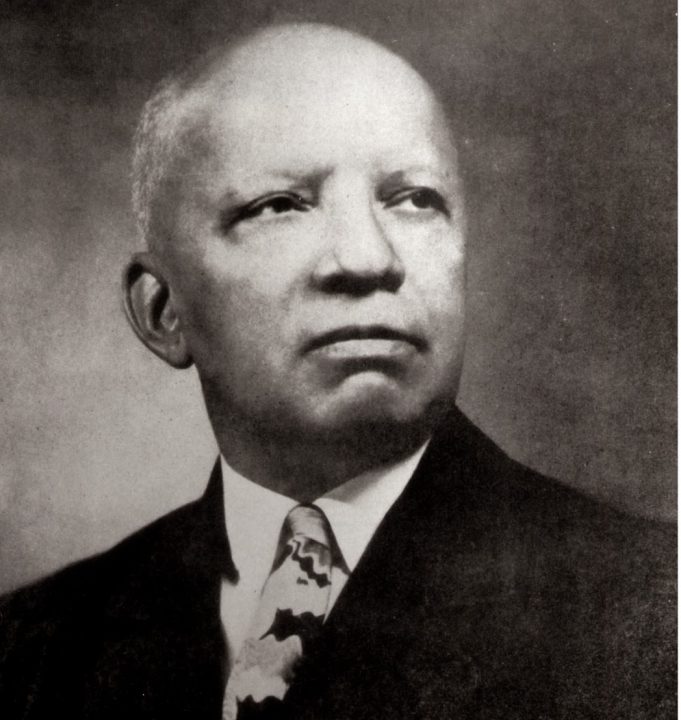

“If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.”

~Carter G Woodson, 1926

When Woodson declared the second week of February Negro History Week, it was done in part because of his frustration that children—black and nonblack students—were deprived of learning about the history and contributions of Black people in America’s schools. Yet, Woodson hoped the time would come when a black history week was unnecessary. He was optimistic that America “would willingly recognize the contributions of Black Americans as a legitimate and integral part of the history of this country.” Sadly, we are not there yet.

Teaching Tolerance, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, in 2014 graded all 50 states and the District of Columbia on how well their public schools taught the civil-rights era to students. Twenty states received a failing grade, and in five states — Alaska, Iowa, Maine, Oregon, and Wyoming—civil-rights education was totally absent from state standards. Overall, the study found less teaching of the civil-rights movement in states outside the South and those with fewer Black residents. The report demonstrated that a key event in Black history was largely disregarded in most schools. Other studies found that mainstream social studies curricula, either largely ignores Black history, misrepresents the subject and generally provides only one to two lessons of total class time on is devoted to Black history in U.S. history classrooms.

A number of states have passed laws requiring Black history to be taught in public schools, with special K-12 Black history oversight committees to include Arkansas, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Mississippi, and Rhode Island. Other states such as California, Colorado, Michigan, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Washington have passed educational laws regarding Black history with no special oversight committee. The mandates are similar in many regards but vary in scope and implementation. State laws in Mississippi and Washington, for instance, only focus on the civil right movement. Both Mississippi and Washington favor a civil rights history that not only is studied within classrooms but applicable to contemporary human rights issues.

Currently, Wisconsin law does not require each school board to provide a minimum number of instructional hours that are dedicated to Black History in state classrooms. The Department of Public Instruction has certainly looked for ways to engage in culturally responsive teaching. However, that is not a substitute for including Black history in the curriculum of our public schools. It is with that understanding that I have drafted legislation that would require Black History to be incorporated into the curriculum of Wisconsin public schools. And there is both a cultural and business case to be made for Black History’s inclusion.

A study done in 2016 by Stanford University called, “The Causal Effects of Cultural Relevance: Evidence from an Ethnic Studies,” found that when ethnic-based classes are taught in schools, students not only made gains in attendance and grades, they also increased the number of course credits they earned to graduate. Education must be relevant, accurate, inclusive and not limited to a single month.