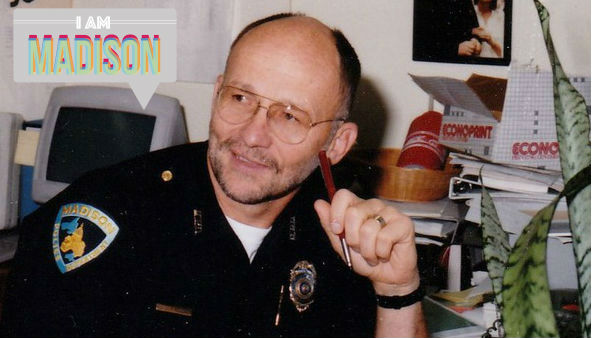

Madison’s Chief of Police is a position that represents the Madison Police Department while also upholding its values such as integrity, diversity, leadership, and a commitment to building a relationship with and serving the Madison community. David Couper dedicated his time and efforts to this cause when he served as the Madison Chief of Police from 1972 to the year 1993.

Madison’s Chief of Police is a position that represents the Madison Police Department while also upholding its values such as integrity, diversity, leadership, and a commitment to building a relationship with and serving the Madison community. David Couper dedicated his time and efforts to this cause when he served as the Madison Chief of Police from 1972 to the year 1993.

Couper took the position as Chief of Police in 1972. Before Couper became police chief the MPD was very different.

Couper took the position as Chief of Police in 1972. Before Couper became police chief the MPD was very different.

“MPD was a traditional police department of the late ’60s and early ’70s,” Couper says. “White, male, high school graduates to whom the ‘law was the law,’ students were suspect, and anti-war protesters the enemy. (Police) were quick to use their fists and nightsticks, but thankfully not their firearms.”

As the successor of hard-liner Wilbur Emery, Couper sought to create a relationship between the police department and the community as well as create a more diverse police department.

“You cannot do the job if you do not have the support of the community, and police officers should represent the community they serve,” Couper says. “When I first became Chief of Police there were 300 employees and only one of them was black.”

Couper worked to create more diversity in the department by instating rules that called for more diversity in the MPD Academy, a program that trains new officers. It is not easy to enact change. When Couper first proposed his ideas for changing the Madison Police Department he was met with resistance from fellow police officers. Although hesitant Couper recruited his officers to his cause to change the MPD for the better.

“I was passionate and persistent on the matter and it took time, about 10 years before it was successful,” he says.

In that time, Couper successfully recruited more women and people of color to train and become police officers of the MPD.

“Half of the classes were composed of women, and people of color” Couper says.

In addition to addressing diversity problems, Couper worked to change the way the MPD interacts with and is perceived by the Madison community.

“You cannot do the job unless you have the support of the community” says Couper.

Couper’s desire to build trust in the community stemmed from the controversy surrounding his predecessor, Wilbur Emery. Emery was the chief of police during the 60s and the height of anti-war protesting. The difference between Emery and Couper is “night and day,” says Madison historian Stuart Levitan. “An ex-marine, Emery was prim and proper, a true cop of the ’50s. He would not have survived the era of community policing.” David Couper was “more focused on community relations,” Levitan says.

In an article from the Isthmus in 2009 by Josh Wimmer titled “ The cop who trains the cops,” Lt. Kristen Roman said Couper’s vision “changed the police department significantly, most notably in terms of getting women into the profession, that’s part of what drew me here.” Another factor that draws people to the MPD is “the philosophy that policing is about community partnerships and exercising responsibly the authority that we’re given” Roman says.

“In the 60s during anti-war protest, the police worked to prevent protesting from happening” Couper says.

During these protests the MPD used excessive force on demonstrators. Police relations were strained. In an effort to counteract this, Couper committed to building a positive relationship between the MPD and the community.

“We helped them protest by facilitating instead of preventing protesting,” Couper recalls. “We trained and supervised our police to do this.”

During his time as Chief of Police, protests were a common occurrence

“People protested anti-war, housing, and apartheid, there were also protests for the Mifflin block party and marijuana rallies,” Couper recalls.

Most importantly, during these protests, Couper and his department did their best to facilitate the events and make sure that everyone was safe while participating. Sometimes there were complaints when Couper did this.

“There was one time when protesters took to the streets and blocked traffic and many people were late for work. People were calling in asking me to resign, saying I wasn’t doing my job by allowing them to block traffic and protest,” Couper remembers.

Couper’s response was to take the criticism in stride: “who is it hurting by allowing them to protest? It’s their right and our job as police officers is to make sure they do it peacefully and that they are safe.”

Being the Chief of Police is not an easy job.

“The job of a police chief is to wear two hats – one hat is as the leader of the police, the ‘top cop,’” Couper says. “But a chief must also wear a second hat–the community’s chief who looks out for their interests and welfare. Wearing two hats always causes conflict both inside the police department and outside in the community. Nevertheless, both hats must be worn.”

Couper retired from the position as Chief of Police in 1993. Today, Couper remains an active member of the community. He became a pastor and he continues to actively advocate for responsible and just policing, often weighing in on topics like police brutality

“Since 9/11 police have become increasingly more militarized,” says Couper.

Couper stresses the importance of discussing this issue, and has been very vocal about the arrest of Madison teenager Genele Laird where police were using excessive force. In an article by Abigail Becker in the Capital Times, Couper says, “We can’t be training police this way anymore.” Couper is invested in this issue and has written a book titled Arrested Development on his thoughts about how police officers can improve

Above all, Couper says, “Police need to sit down with the community and discuss these issues.”

“There will always be tensions between the police and the community, especially as our nation diversifies. Two big mistakes in America is 1) thinking everything has to do with race and 2) thinking none of this has to do with race,” he says.

Couper has left a lasting impression on the Madison Police Department. He changed the department to be more inclusive and diverse and successfully bridged the gap between the police department and the community. In Couper’s 20 years as police chief, his proudest accomplishment is the institution of Community-Oriented Policing.

“I worked with educated, well-trained, creative, and caring cops,” he says. “Excellence in policing is now up to them. They need to stand up and speak out when mistakes are being made and be committed to learning from those mistakes, being accountable and doing better in the future.”

I Am Madison is funded by Madison Community Foundation as part of its Year of Giving.