In the midst of the pandemic, Dr. Crystal Moten joined an online writing group in the Association of Black Women Historians for their support during the pandemic as she started the writing and research for a project she was working on.

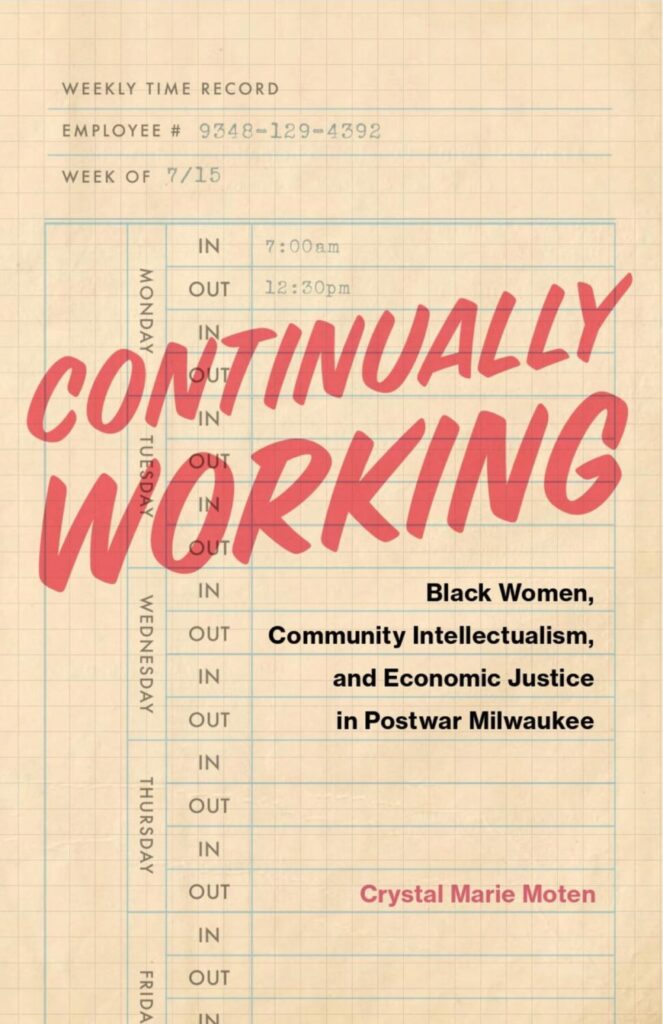

The community support and encouragement from the group led her to finish and publish her book, “Continually Working: Black Women, Community Intellectualism, and Economic Justice in Postwar Milwaukee,” which are the stories of Black women who resisted against employment inequality in Milwaukee from the 1940s through the 1970s.

“I would get up every morning and write with a community of Black women,” Moten said. “It was that community that helped push me from apathy to action.”

Her interest in creating a book to share these experiences Black women endured started while she was attending graduate school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. As a Chicago native, she was interested in sharing the diverse narratives of the Midwest.

“When we’re thinking about Black lives, and Black experiences in the Midwest, it’s important to understand those local stories,” she said. “Thinking about the size of Milwaukee and the fact that many folks who migrated from the South to Chicago, would get to Chicago and then say, ‘Wow, this is not the promised land that I thought it would be. Let me continue further North.’ That further north was 90 miles away to Milwaukee. And there, they continued to face economic injustice, residential segregation, and unequal education.”

Moten shared why it was important for her to analyze Black women’s experience in Milwaukee’s workforce during this time period. She wanted to discover how Black women responded to these efforts to keep them economically marginalized.

“One of the main contributions I see the book making is really thinking about Black women’s contributions to the struggle for civil rights and economic justice, which tend to be masculinist in nature,” she said. “We tend to think about the charismatic male leader to the detriment of understanding Black women’s contributions.”

She has always been interested in Black women’s gendered experiences throughout history. When she was conducting this research, she knew it was crucial to explore Black women’s specific experiences in the workforce postwar.

“If you think about the history of Milwaukee, it was considered and characterized as a worker’s paradise,” she said. “In the book, I share that certain workers could get one job in the morning, and then ‘Oh, I don’t like it,’ and quit, then get a different job in the afternoon. That wasn’t the case for Black women. Black women were still working in personal and domestic service. In the 1950s, 50% percent of Black women in Milwaukee were in domestic and personal services. The question becomes: What are the economic opportunities for Black women in this working-class industrial paradise?”

Moten talked about the importance of including a gendered analysis in her efforts to explore Black women’s experience in the workforce in Milwaukee during this time. In her book, she uses the term “Jim Crow job system” to describe the legal, social, and cultural structures that combine to exclude Black workers from accessing, participating in, and progressing in employment.

“I really wanted to call the reader’s attention to the fact that Jim Crow was just not a southern phenomenon,” she said. “Jim Crow was a national cancer. We are still experiencing the ill effects of Jim Crow to this day, in terms of segregation and discrimination in employment. My use of Jim Crow was to signal that when we think about employment and economic injustice. We have to think about the ways in which segregation and discrimination, both legal, and also in practice, impacted Black women’s ability to obtain quality and fair employment.”

Through her research, Moten found that there were connections between the economic oppression from the government and racist, white people’s efforts to impede on Black women’s economic opportunities. Despite the economic stress of this institutionalized racism and economic oppression, Black people and women found ways to lean into community and create safe spaces for themselves.

One of these spaces was the Bronzeville District. Then and now, this area was a space for Black community members to come together, celebrate and embrace their culture.

“Bronzeville is really important because of Black people and what black people create there,” Moten said. “It’s the ultimate example of taking lemons and making lemonade. Black folks were segregated into a very small, square footage in the city of Milwaukee. But what do they do with that community? They create their own businesses, their own organizations, their own community activities, they create love, joy and happiness and peace and community.

“What you have is Black folks kind of saying, ‘Okay, in the midst of this hyper-segregated area, we are going to create our own communities, we’re going to create our own restaurants and nightclubs, and beauty shops and banks.’ It becomes this space of resistance, not only in the sense of fighting against injustice, but fighting to live, thrive and be alive.”

Moten spoke about the book’s meaning to her and her growth as a historian, a Black woman, and a Black working woman in the United States. Through a book that took on a life of its own, she hopes readers enjoy learning about the resistance and resilience of Black women in Milwaukee.

“I really hope that people will be inspired by the creative ways that Black women have understood and responded to whatever circumstances they find themselves in,” Moten added. “We can look through history to understand and to learn from our ancestors. Not that history repeats itself, because I don’t believe that. I do believe that there’s so much that we can learn from the folks who’ve come before us. And that we should treasure and share these stories. It’s not just for Black people, it’s for all people. All people need to know and understand these stories. I hope that the book will get as broad an audience as possible.

“Because I do think that we can learn from Black women if you just listen to what they have to say.”

To learn more about Dr. Moten, her research and her book, visit her website.